Strengthening Participation for Policy Influence Lessons Learned from Trócaire’s

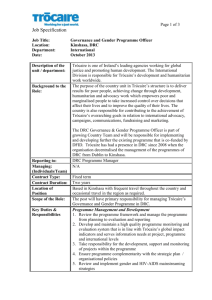

advertisement