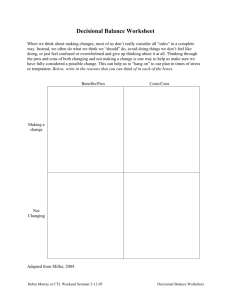

S TUDYING DECISIONS

advertisement