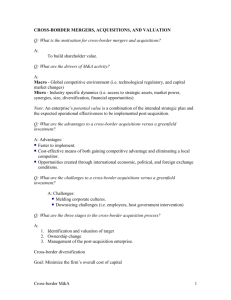

E P H

advertisement