NOT READY TO MAKE NICE BEYOND IN ThE ARTWORlD AND 1

advertisement

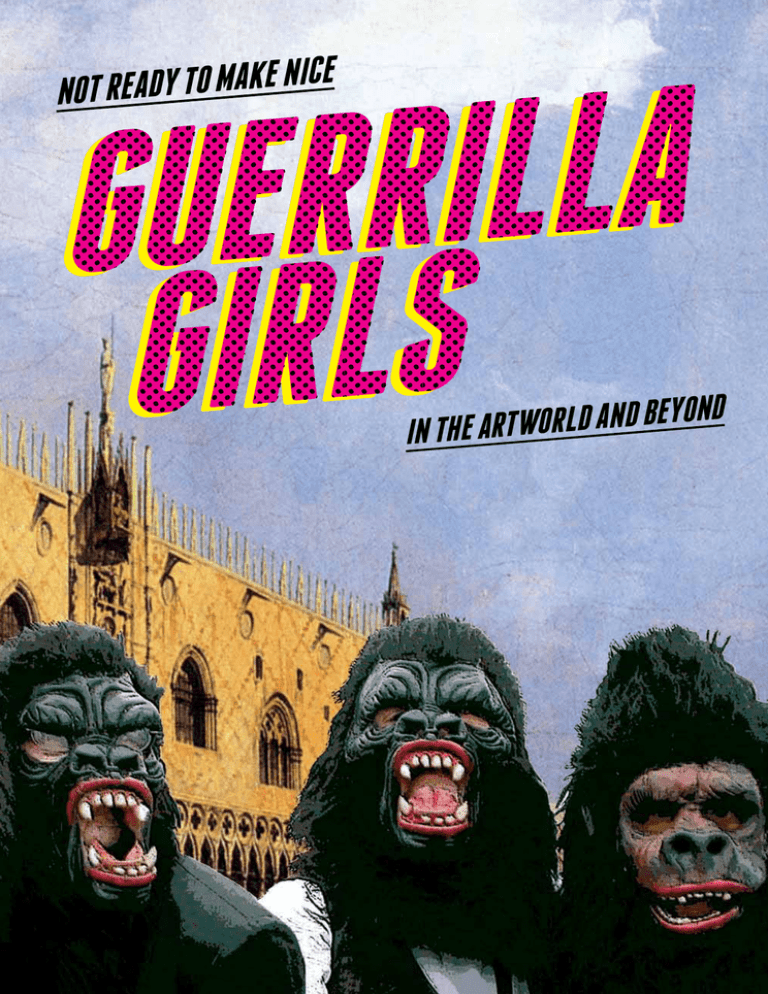

E C I N E K A M O T Y D A E NOT R eyond B and d l or W art e In th 1 2 Contents Foreword: Art and Occupation 2 by Jane M. Saks Not Ready to Make Nice 4 by Neysa Page-Lieberman The Feminist Roots of the Guerrilla Girls’ “Creative Complaining” 23 By Joanna Gardner-Huggett Guerrilla Girls, Graffiti, and Culture Jamming in the Public Sphere 27 by Kymberly N. Pinder 31 Exhibition Checklist 32 Acknowledgments Cover image taken from Benvenuti alla Biennale Femminista, first shown at the 2005 Venice Biennale. Foreword: Art and Occupation by Jane M. Saks, Executive Director, Ellen Stone Belic Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media There are times in which immense social upheaval and aesthetic innovation rise simultaneously to influence profound shifts in dominant institutions and generate a wide social constellation. We can only hope that the present is one of those times—a time in which a cultural and social seachange occurs; a virtual and actual wave of creative experimentation and engagement shifts the social geography. It has happened before. Cultural production has an inherent ability to insert the democratic practices of free speech and institutional critique into spaces that actively or passively prohibit them. Throughout history, in times of revolution, movements have skillfully exploited and enlisted the essential mix of art, politics, free speech, and action to create and protect democratic spaces in spite of—and directly on the turf of—powerful institutions. In 2011, we began to witness people around the world risk everything to occupy public space -- demanding to be seen, heard and exercising their agency to participate in the political and social arena. Globally, this moment is particularly alarming for its serious challenges, stark and growing historic inequalities, severe and escalating risks, and its peculiar similarities to other troubling times. It has also been a period of extreme social and political shifts brought about by undeniable and fierce activism. Since the beginning of 2011, people across the globe and on multiple continents have proved that individual action can bring about collective social change. In this context, 4 collective cultural production focused on direct action and communal participation centralizes key questions: how is culture accessed and how does that influence collective cultural practices? These are the challenges, questions, and interests that first motivated us at Columbia College Chicago to create a year-long, campus-wide initiative with the Guerrilla Girls, led by the Ellen Stone Belic Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media and the Department of Exhibition and Performance Spaces. The idea of presenting the breadth of the Guerrilla Girls’ practice at this moment is linked to the recent and vibrant activism beginning in 2011, especially the Occupy Movement and historic movements such as the Arab Spring. These are direct democratic practices that reclaim the right to inhabit and critique public spaces. They enlist the oldest techniques of democratic agency and locate them at the center of new media and technology. The creation of culture, in its most concrete applications, mirrors and reflects back sharp and often invisible realities to the dominant and exclusionary institutions that help produce them. Invisibility, visibility, and power have been at the center of the Guerrilla Girls’ work for more than three decades. A self-described group of radical feminist artists, the Guerrilla Girls were established in New York City in 1985. They became known for using creative graphics, actions, and exhibitions to promote women and people of color in the arts. Their first work was putting up posters anonymously on the streets of New York to illustrate the gender and racial imbalance of artists represented in galleries and museums. They were, simply or not, trying to get museums to represent a larger, more diverse vision of culture. They were investigating who makes art, why, and how it gets constituted and experienced. I remember walking down the city streets as an undergraduate college student in 1980s New York when I first saw a Guerrilla Girls’ poster layered across a SoHo wall. The information was at once exhilarating—publicly naming the inequality we all knew was true—and, at the same time, exposing that the facts and attitudes were even worse than we thought. The 1980s was another time when institutions shifted and coalesced, putting elements into motion that continue to this day to shape our lives: Reagonomics (justified greed at a new and extreme level and the dismantling of social support systems), the early years of the AIDS epidemic (immoral policies and cruel declarations that said it was somehow a justified plague), the growing LGBT rights movement, the increasing global awareness of the anti-apartheid movement, the continued struggles for racial and gender equity, and more. Through this, the Guerrilla Girls encouraged people to fight and laugh at the same time. They have since expanded their activism to examine Hollywood and the film industry, popular culture, gender stereotyping, and corruption in the art world. The Guerrilla Girls have worked in forty-eight states and countless countries. Their books are popular among political activists, scholars, and art historians, and have become central curriculum in art history, women’s and gender studies, cultural studies, and political science. The Guerrilla Girls inspire other artists to enlist an activist practice authentic to the times and collective struggles. Their model of institutional critique and subversion has prompted diverse cultural responses from artists who now work to present and represent different multi-generational, global perspectives focused on issues of invisibility and visibility. Both building on and diverging from the Guerrilla Girls’ critique of patriarchal subordination of women, a vast range of new work has emerged with deep feminist implications that differ in form, content, and medium, but remain indisputable in presence and unstoppable in necessity. Not Ready to Make Nice includes essays by the exhibit curator, Neysa Page-Lieberman, and scholars Joanna Gardner-Huggett and Kymberly Pinder, each of whom articulate a range of perspectives and contextualize the work of the Guerrilla Girls. The catalogue also includes the work shown in the exhibition, bringing together new and significant pieces and projects supporting the breadth of their multi-decade vision. The Guerrilla Girls continue to exist and work on a particular edge. Their work illustrates a belief that culture and cultural institutions should represent the whole of a society. Their relentless efforts combine artistic expression and humor with irrefutable information to disarm the powers that be—forcing them to examine themselves and inviting each of us to do the same. Museums Unfair to Men/Museums Cave In To Radical Feminists, 2008 Not Ready to Make Nice by Neysa Page-Lieberman, Curator and Director of the Department of Exhibition and Performance Spaces The Guerrilla Girls have been powerfully and consistently active since first breaking onto the art scene in 1985. The feminist activist group, who only appear in gorilla masks, has remained anonymous for nearly three decades, earning the name, “the masked avengers.” Beginning with their courageous poster campaigns of the 1980s and 90s and continuing with large-scale international work of the present, they brilliantly take on the art establishment in a way that has never been seen before or since. Using “facts, humor and fake fur,” they have exposed the discriminatory collecting and exhibiting practices of the most feared dealers, curators, and collectors in the artworld. Masking their real identities and appropriating the names of dead women artists, they continue to reveal shocking truths in a way that marginalized groups cannot do without repercussion. The exhibition Not Ready to Make Nice illuminates and contextualizes the important past and ongoing work of these highly original, provocative, and influential artists who champion feminism and social change. The show sets itself apart from past exhibitions of Guerrilla Girls work in two ways. First, most of the work included has been made within the past decade and has rarely, if ever, been seen in the United States. As the Guerrilla Girls’ early campaign moved outside of New York, around the country, and finally abroad, they also expanded their work to include non-visual arts media, taking on everything from the discrimination of women film directors to the vulnerability of America’s homeless population. The second goal of the exhibition is to provide historical and physical context for this work, especially considering that none of the featured pieces in the exhibition were originally designed to be shown in an art gallery. The earliest posters were plastered on walls and fences in New York City’s SoHo 6 neighborhood (then the epicenter of the art scene), and adhered quickly in the middle of the night amidst rock posters and advertisements. On the other extreme, much of this work was designed for large-scale banners and billboards, to awe viewers with monumentality and provocative messages. To capture the context and appearance of each piece, projected images of the work in original settings and behind-the-scenes anecdotes in the Guerrilla Girls’ own words fill the gallery. The exhibition’s focus on this contemporary work was a vital part of the collaborative process between the curator, college partners, and the artists. As described in Jane Saks’ illuminating foreword, significant current events, which provide societal and cultural parallels to the statements in the exhibition, truly punctuate the relevance of the Guerrilla Girls’ current work. Not Ready to Make Nice, an expansive multimedia exhibition, illustrates that the work of the anonymous, feminist-activist Guerrilla Girls is as vital and revolutionary as ever. Early Work: Defining a Practice and Philosophy A small selection of the Guerrilla Girls’ most iconic pieces from the 80s and 90s sets the stage for their contemporary work and provides a glimpse into the group’s formative decisions that built their foundation. The Guerrilla Girls were not the first collective of feminist artists to confront the artworld’s discriminatory practices.1 However, they were the first to attain real and sustaining attention from the media. Early success may be explained by their intriguing anonymity, the outrageousness of the gorilla masks, or the fear in the art community that no one was safe from a Guerrilla attack. But more likely, their quickly achieved fame was due to their finely honed presentation style characterized by succinct and quick-witted messages and indisputable facts. Their incisive institutional critiques revealed that the artworld did not exist in a vacuum and was vulnerable to the same societal problems affecting everyday life. The group explains, “Many people think the artworld is above it all. They don’t think it’s subject to the same forces as other areas of society.”2 The work challenged people’s acceptance of the linear, patriarchal presentation in art museums as the definitive story of art history. These Artists, 1985 (Fig. 1) and These Galleries, 1985 (Fig. 2), were the posters that started it all. A press release promised more to come and warned: “Simple facts will be spelled out; obvious conclusions can be drawn.”3 These were soon followed by their famous “report cards,” highlighting horrifying statistics about the few, if any, women artists and artists of color that were represented in New York’s top galleries. Although many were aware of the inequity, disseminating the embarrassing numbers shamed dealers, collectors, and curators who soon came under extreme pressure to make changes. Jane Saks recalls first encountering the Guerrilla Girls’ work as an undergraduate at Sarah Lawrence: “The first thing I felt was how smart and bold it was that someone was just putting this information out there. We all knew how inequitable the art world was (mirroring our society as a whole) for any artist who was not white, male, straight, had access and was part of the power network. The Guerrilla Girls built an emotional and intellectual response with quantifiable information. It was a simple, concrete and unadulterated public declaration. And, this at a time when the mainstream political forces were clamping down on activism. It was in the midst of the Reagan years, which sanctioned a focus on wealth and the individual, the privileged and the powerful. At the same time, and not coincidentally, there were so many remarkable things happening in the creative and socially engaged realm.”4 Another early highlight was The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist, 1988 (Fig. 3). The collective jokes: “The word on the street was, ‘The Guerrilla Girls are so negative! All they do is complain!,’ so we took this criticism to heart and decided to do this poster to make women feel better about their situation.’” While this was not literally a feel-good poster, citing such “advantages” as “Having the opportunity to choose between career and motherhood” and “Seeing your ideas live on in the work of others,” it gave voice to the secret frustrations of countless women. Works like these drew in fan mail, and lots of hate mail: “We were always a little afraid because we really thought that we were dealing with dangerous stuff and if it were discovered who we were, it would be the end of our art careers.”5 But the group was astounded to get letters from women in fields as diverse as meteorology to mortuary science, saying that the Guerrilla Girls work defined their worlds, too. Upping the ante like never before, a smash hit came when the group released one of their most famous works of all time, Do Women Have to be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum, 1989 (Fig. 4). This work, commissioned by the Public Art Fund, was intended to be a billboard in Manhattan. The challenge of a first-ever large-scale public work excited the group and prompted them to invent the now-infamous “wienie count.” The Guerrilla Girls went through New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and simply counted male and female artists versus male and female nudes in the artworks. In the resulting work, the disheartening statistics were placed next to an image of Ingres’ classic Grande Odalisque, masked in the signature confrontational gorilla head. The PAF rejected the design, possibly fearing taking on the Met in public, so the group ran it themselves on rented space on the sides of city buses. This very public action increased the Guerrilla Girls’ visibility and earned them a cult following; “It was immediately reshown by us and our followers all over the place. . . . We wanted to reach a wide audience, not just the art crowd. . . and most people don’t know these issues.”6 The group has updated “The Met” piece many times, but the statistics have not improved—until 2011. While the percentage of women artists on view has not changed, the percentage of nude women has dropped and there are now more images of naked men on view; the “wienie count” continues to grow. Politics: The Artworld is Not Immune to its Discriminatory Society After the success of the early posters, the Guerrilla Girls quickly widened their cause to include politics and broader issues of exclusion. Works such as Battle of the Sexes, 1996, which exposed harsh realities about the workplace, and Pop Quiz, 1990, which asks, “Q: If February is Black History Month and March is Women’s History Month, what happens the rest of the year? A: Discrimination.,” reflected the group’s insistence that the artworld will always be affected by larger political and societal tensions. The Guerrilla Girls have continued to confront war, anti-women congressional decisions, racism, and tokenism in many of their works: posters, newspaper spreads, demonstrations, and more. Their recent work has become even more bold and daring, with highly successful campaigns and public works such as The Birth of Feminism Movie Poster, 2001 (Fig. 5), Estrogen Bomb, 2003 (Fig. 6), I’m Not a Feminist, But. . . , 2009 (Fig. 7), and Disturbing the Peace / Troubler le Repos, 2009 (Fig 8). These four works tackle issues such as violence against women, misconceptions about feminism, and the perpetuation of misogyny throughout history. Birth of Feminism and I’m Not a Feminist, But. . . use humor and pop culture references to address derogatory associations about feminism and female empowerment. Both works use tonguein-cheek approaches to illustrate the trend of young women rejecting the word feminist, while still embracing the tenets and goals of the feminist movement. Misplaced negativity and fear-driven associations with feminism also drive the message behind Disturbing the Peace / Troubler le Repos, which marks the twentieth anniversary of the worst mass murder in Canadian history when a gunman sought to “fight feminism” by murdering fourteen female engineering students. The Guerrilla Girls graffitied a wall with misogynist hate speech from world history, showing how it has always been 7 acceptable to make hateful public statements about women, highlighting horrific quotes from Confucius to Picasso to Eminem. Estrogen Bomb, first appearing in the Village Voice in 2003, was the group’s sardonic, yet decidedly non-violent solution to the war on terror. They proposed a destructionfree, hormone-filled weapon that led people to “throw down their guns, hug each other, say it was all their fault,” and solve other problems afflicting the world such as poverty and absence of healthcare. Going Global: It’s Worse. . . Everywhere Sadly, the Guerrilla Girls never run out of issues to address and, thus, work to make, always compelled to confront and critique institutions and prejudices around the world. Much of their new work takes the form of invitations and commissions; even the Guerrilla Girls have been surprised by the demand for their work. They have made no shortage of enemies, humiliating powerful institutions, publicizing the names of the supposedly untouchable, and distributing their work far and wide.7 But their call to action has been telling—New York is not unique in its regressive exhibition practices and in fact, elsewhere may be even worse. In 2007, the Guerrilla Girls were invited by the Washington Post to critique the museums in Washington, D.C. in a special section on feminism and art. They designed a tabloid, Horror on the National Mall (Fig. 9), to reveal the appalling statistics that floored even the staff working within these institutions. The Girls recently reflected, “The Washington Post project was so telling: here you have tax payer supported institutions and exhibitions in a majority black city, but still there are almost no black artists on the walls.” While frustrating to see these problems persist, a marked difference now is that “people are embarrassed when these issues are pointed out. Before they would say that it was not possible or justifiable to show more women or artists of color.”8 Many individuals working on the inside knew of these problems but felt powerless to resolve them—this work and the resulting media attention gave them the ammunition to create change from the ground up. The 2005 Venice Biennale was called “the first feminist biennale” by the Guerrilla Girls who were asked by Rosa Martinez and Maria de Corral—the first women directors of the Biennale in its 110 year history—to critique the extremely influential international art fair. The result was Benvenuti alla Biennale Femminista (Fig. 10), which then led to a sweeping critique of Venice itself in Where are the Women Artists of Venice? (Fig. 11). Research revealed that almost every museum in Venice owns work by women, but almost all of it is relegated to basement storage. Thus, the answer to the question, “Where are the women artists” is, literally, “underneath the men.” The poster is illustrated with an iconic still from Federico Fellini’s film, La Dolce Vita, showing Marcello Mastroianni mounting Anita Ekberg. Other works, such as Irish Toast, 2009 (Fig. 12), and The Future for Turkish Women Artists, 8 2006 (Fig. 13), were similarly commissioned by institutions to shed light on enduring and galling local statistics. Drawing from traditional local customs and rituals, these works contrast the two countries’ rich cultural inheritances with their minimal support or representation of diverse voices. While Ireland toasts, “May your academies be seminal,” Turkish coffee grounds reveal grave predictions: “Curators who forget women when they organize museum exhibitions and biennials will be banished to the US and EU where such backward ideas belong.” With so many world museums currently readdressing their collections, it is not surprising that the Guerrilla Girls have turned the spotlight on Chicago, one of the world’s most metropolitan and multicultural cities, boasting some of the largest collections of art and cultural objects. Some may think Chicago’s major art institutions would rank better than other cities, considering Chicago has a long and deep heritage of supporting women artists and artists of color. The School of the Art Institute, for example, was one of the first art schools in the nation to admit black students; there are flourishing cultural museums like the DuSable Museum for African American History and the National Museum of Mexican Art; numerous culture-shaping feminist art collectives (Artemesia and Woman Made, for example) and many more institutions whose mission it is to support diversity. However Chicago’s museums demonstrate the same problems as those documented in the Guerrilla Girls’ body of work.9 Chicago Museums: Time for Gender Reassignment, 2011 (Fig. 14), uses an image of the Art Institute’s iconic Beaux-Arts façade, featuring a cornice carved with the names of white, male historical figures, as a symbol of the predominance of similar trends inside the buildings of Chicago. The Guerrilla Girls pose as cherubic action heroes flying down from the heavens to remedy the situation by installing a new frieze that includes a more inclusive representation of art historical figures. The decision to use cherubs is particularly witty as they are genderless and thus better poised to fight bias. Gathering statistics directly from institutional websites and from work on view in the galleries in fall 2011, the Guerrilla Girls challenge Chicago to tackle the lack of diverse voices in its leading institutions, demanding that an accurate picture of history is impossible when the voices of 70 percent of the population are excluded.10 Hitting the Mainstream: Taking on Hollywood Around the turn of the twenty-first century, the Guerrilla Girls decided to address the proverbial 800-pound gorilla in the room—Hollywood. Prompted by correspondence from female film directors and an invitation from The Nation, who wanted to feature a project about women in film, The Anatomically Correct Oscar, 2002 (Fig. 15), was born. This work had its biggest impact at the Academy Awards where it was shown on a billboard just blocks away from the event. “We redesigned the Golden Boy to more closely resemble the guys who take him home each year. . . . He’s white and male, just like the guys who win.” The group considers Hollywood to be “an irresistible target of hypocrisy,” in which Hollywood’s professed liberal values are at odds with its inequality of employment opportunities for women and people of color.11 The internationally popular follow-up work, Unchain the Women Directors, 2006, was first shown as a billboard in Hollywood and soon translated into other languages. It features King Kong bellowing bad news for women in film. The Spanish language version (Fig. 16) debuted in Mexico City on the side of an artist-in-residence building. The Guerrilla Girls are planning more projects addressing the entertainment industry, not only because of the encouragement and partnership of activists working in film, but because the “Hollywood stuff gets a huge bang for the buck because there’s so much press set up to cover Hollywood. Much more than in the artworld. . . . It’s a new story for them. . . there’s this huge interest.”12 Future: Where to Now After almost three decades of fighting the establishment, the Guerrilla Girls find themselves in the paradoxical position of being featured in exhibitions and performances at the very institutions they have, and continue to, critique. They receive invitations from institutions wanting their museum or geographical location assessed by the group. The Guerrilla Girls have critically considered how their work might be compromised by such requests, but ultimately decided to accept the invitations, as is seen in the Washington D.C. work, Project Ireland, and elsewhere. Whereas at one point, their work could only be executed from the outside, they can now execute the same goals from within, where all parties are involved for the same reason: to rectify inadequate collecting and exhibiting practices. Occasionally museums invite the Guerrilla Girls to assess their own collections and yet remain incredulous of the staggeringly poor results. Nonetheless, this collaborative exercise can lead to real systematic change where it becomes increasingly important for the success of these institutions to address internal challenges. In addition to partnering with art institutions, the Guerrilla Girls have dedicated a large portion of their time to working with college and university students. While still at the height of their fame, they feel a need to ensure their legacy and that of the feminist collectives that came before them. Working with the next generation of activists is central to fulfilling this mission. They have embraced the information age, making their work available for download and distribution on their website, and teaching their techniques to students all over the world. In 2008, they teamed up with the Brainstormers, a collective that came of age watching the Guerrilla Girls wreak havoc on the artworld. The Brainstormers employ some of the classic techniques of the Guerrilla Girls—compiling screenshots of contemporary art galleries’ male-centric artist rosters and incorporating a punchy and flamboyant sense of humor in their work—but they have a decidedly new media- and performance-based approach to toppling ivory tower power structures. Together the two groups developed an “all-inclusive” action called Get Mad: “A street action for feminists and anti-feminists, everyone welcome!” While feminists completed mad-lib style postcards addressed to the most discriminatory art galleries in New York City, antifeminists were welcomed into a fake protest group called MAN (Male Art Now) (Fig. 17), in which they complained about recent feminist art exhibitions that included zero percent men, accusing museums of caving to radical feminists. The Guerrilla Girls’ work with students in Chicago alone speaks to the importance they place on mentorship and collaboration with the next generation of arts and culture workers. In 2010, they were invited by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to deliver the commencement speech. While never shying away from an opportunity to critique an institution from within its very own walls, the group took digs at the school’s parent institution, the Museum of the Art Institute, while simultaneously advising the audience to “love museums, but be tough on them. . . demand ethical standards. . . and make sure your favorite museum collects the whole story of our culture.”13 Most recently, in the fall of 2011, they spent a week at Columbia College working with hundreds of students in numerous workshops, listening to students articulate their own challenges and frustrations as they prepare to enter the professional world. The Guerrilla Girls encouraged students to work towards collaboration, to work against competition, and to embrace their frustration and anger and become “creative, professional complainers.” The group effortlessly galvanized students, faculty, and staff to organize their own campaigns, and to fear nothing.14 Through their increasingly expansive work, lectures and workshops, the Guerrilla Girls have succeeded in changing the worldviews of countless individuals. Many have had their eyes forced open to acknowledge that most of the artists they have studied or promoted are part of a white, Western, patriarchal canon. And many can no longer view any work of art—be it an exhibition, film, performance, or even a television show—without noticing, and often protesting, the all too common lack of women and people of color. This shift in the cultural psyche has occurred in institution-byinstitution, even individual-by-individual, and from that there is no turning back. I would like to thank the Guerrilla Girls, Stuart Carden, and Brandy Savarese for their contributions to this essay. I also extend my gratitude to: Jane Saks, Sara Slawnik, and Kipa Davis for their partnership and unyielding vision in producing this program; Mark Porter, Jennifer Murray, and Julianna Cuevas for lending their talent and dedication to developing the exhibition; Joanna Gardner-Huggett and Kymberly Pinder for their thought-provoking essays; and Ben Bilow for his inventive design work. Together this group has brilliantly captured the spirit and energy of the Guerrilla Girls body of work, while adding a riveting and significant chapter to their history. 9 Fig. 2: These Galleries, 1985 Fig. 1: These Artists, 1985 2. The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist, 1988 1. These Artists and These Galleries, 1985 10 Fig. 3: The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist, 1988 Fig. 4: Do Women Have to be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum?, 1989 -2012 11 Fig. 5: The Birth of Feminism Movie Poster, Rotterdam, 2007 12 Fig. 6: Estrogen Bomb, 2003–2012 14 Fig. 7: I’m Not a Feminist, But. . . , Belfast, 2009 Fig. 8: Disturbing the Peace / Troubler le Repos, 2009 –2012 15 16 Fig. 9: Horror on the National Mall, 2007–2012 17 Fig. 10: Benvenuti alla Biennale Femminista, 2005–2012 18 Fig. 11: Where are the Women Artists of Venice?, 2005–2012 Fig. 12: Irish Toast, 2009–2012 Fig. 13: The Future for Turkish Women Artists, 2006–2012 20 Fig. 14: Chicago Museums: Time for Gender Reassignment, 2012 21 22 Fig. 15: The Anatomically Correct Oscar Billboard, Los Angeles 2002–2012 Fig. 16: Unchain the Women Directors / Hay Que Quitar Las Cadenas a Las Mujeres Directores, Mexico City, 2006–2012 Fig. 17: M useums Unfair to Men/Museums Cave In To Radical Feminists, New York City, 2008 24 The Feminist Roots of the Guerrilla Girls’ “Creative Complaining” By Joanna Gardner-Huggett, Ph.D., DePaul University Emerging as feminist activists at a critical moment in the 1980s, the Guerrilla Girls faced the reality that the significant women’s political gains of the previous decade were under threat. The failure of the Equal Rights Amendment, challenges to reproductive rights, and Nancy Reagan polishing silver in the White House became the emblems of womanhood.1 Women in the artworld fared no better. Male artists, such as Eric Fischl, David Salle, and Jeff Koons, were celebrated for their images of objectified women and rewarded with instant fame and record-breaking sales.2 Simultaneously, the Guerrilla Girls joined a large field of women artists, including Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, and Ilona Granet, who countered the misogyny of the commercial art market through the appropriation of advertising and media. Disseminating their subversive messages through stickers, posters, street signs, and t-shirts, these artists staged public interventions in SoHo, New York City’s thriving art district. But the Guerrilla Girls offered something new by working collectively and embracing anonymity. Donning gorilla masks, appropriating the names of dead female artists, and embracing the absurd and satire, the Guerrilla Girls disrupted the old order and established new voices of authority that demanded a visibility for women artists and artists and color. The early history of the Guerrilla Girls is well known, but what is not fully explored in art historical scholarship is how the group builds on numerous tactics established by feminist art activists in the 1970s. Until recently critics and historians created a strict divide between the essentialism of the 1970s versus the postmodernist discourse of the 1980s where language replaced the female body as the site of political debate, forging a “permanent rupture” and negating any links between practitioners in this period with their predecessors.3 Although the Guerrilla Girls do not cite specific collectives or feminist artists as models for their own work, situating their practice—what they call “creative complaining”—within the larger chronology of feminist collaboration is a way to amplify their innovations and their ability to maintain status as the “conscience of the artworld” for more than twenty-five years. As a collective, the Guerrilla Girls operate on the consensus-model employed by women artists’ cooperatives since the early 1970s as a way to reject patriarchal modes of administration.4 Working in New York there were numerous examples to emulate, such as A.I.R. Gallery formed in 1972 and SoHo 20 opened a year later.5 However, an even stronger parallel can be drawn between the Guerrilla Girls and the Heresies Collective, which was founded in November 1975 as a journal to address the intersection between feminism, art, and politics. It resisted other journals’ dedication to monographic studies of women artists and instead explored a particular theme in each issue, for example, violence, lesbian women artists, and third-world women. Each issue was developed by a smaller “collective” within the larger membership, as well as a selection of outside contributors who held expertise on that particular subject.6 Utilizing similar strategies as the Heresies in developing their campaigns, the Guerrilla Girls commit to a specific topic, generate ideas, refine them, and realize the project. In order to ensure an image or text is communicating effectively, they test it on people who have not been immersed in creating the issue for an extended period.7 Rather than 25 produce a publication that targets a specific population already dedicated or at least interested in feminism, the Guerrilla Girls’ posters, stickers, and actions turn to the street and particular institutions responsible for discrimination. The poster Guerrilla Girls’ 1986 Report Card (1986), for example, lists powerful art dealers in SoHo and documents how many solo shows each gave to women (over two seasons) with most receiving a failing grade. The use of “plain-spoken” language and signature graphics forces the art community to confront and become accountable for questions too easily dismissed in private.8 The impact of these posters was felt immediately. New York dealer Patricia Hamilton remarked in 1987, “. . . it’s getting to the point where you can’t not show women. You look like a jerk.”9 Feminist art activists have long relied on tallying discrimination against women, which is central to the Guerrilla Girls’ success. For instance, they simply walked through the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and counted the number of “wienies” and female nudes on view for their now iconic poster Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? (1989). Sometimes the group acquires statistics through the assistance of a mole as in 1987 when a “deep throat” in the development office of the Whitney smuggled out confidential data and information about the museum’s trustees. Their research and information culled from museum bulletins formed the basis of the Guerrilla Girls’ Clocktower exhibition held the same year and examined the visibility of women in the Whitney Biennial, which is considered to be the preeminent venue for contemporary artists working in the United States.10 It included an installation “Can you score better than the Whitney Curators?,” inviting visitors to throw darts at a large mammary gland in an effort to draw attention to achieving better gender and racial parity in the museum’s biennial exhibitions. Their accompanying “Banana Report” not only exposed the sexism and racism long part of the museum’s biennial, but also trustees’ roles in companies that manufacture products, such as cosmetics and cigarettes, marketed to women and people of color who are then denied representation in the exhibitions funded by the profits.11 These statistics demonstrated that the state of affairs had not improved since the group Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee protested the Whitney in 1970. Formed in order to apply pressure to New York museums that ignored women artists’ production, Ad Hoc Women picketed the Whitney Sculpture Annual that year, demanding 50 percent women and 50 percent artists of color. As a result of this pressure, the percentage of women shown increased from an average of 5-10 to 22 percent in 1971.12 However, the Guerrilla Girls revealed that once the pressure eases so does the commitment to diversity. The Whitney clearly still feels the sting of both events, highlighting documentation of both actions in a small exhibition organized by the education department in honor of the 2010 Biennial, in 26 which they took the opportunity to announce that, for the first time, more women than men were featured, twenty-nine female artists versus twenty-six male artists. Of course, the organizers were quick to qualify that the curators “did not choose the artists specifically on the basis of gender and race,” suggesting that they made selections based on “quality”—a long held institutional defense against accusations of discrimination.13 Further, the small exhibit intimates that the question of gender equality is now part of the historical past despite taking forty years to achieve such parity. It will be interesting to see whether the 2010 Biennial will become an “exception” to the Whitney’s history or if another “Banana Report” is in the cards. When the Guerrilla Girls formed in 1985, they were reacting to what they perceived as ineffective methods of protest among feminist activists in the arts. Walking a picket line simply did not provoke any reaction or results and merely affirmed the myth that feminists were dull and too serious.14 Instead, the Guerrilla Girls, as their name and actions imply, employ guerrilla tactics, raucous humor, and spectacle as a means to connect with an audience, and to prompt political transformation. Take, for example, the panels “Hidden Agender: An Evening with Critics” and “Passing the Bucks: An Evening with Art Dealers” held at Cooper Union in May 1986. At both events major figures from the artworld, such as the critics Grace Glueck, Carter Ratcliff, and Stephen Westfall, and the dealers Ronald Feldman, Tony Shafrazi, and Holly Solomon, were invited to discuss why women artists were not visible in the artworld. The journalist Carrie Rickey moderated both evenings, which meant that Guerrilla Girls were free to play with the audience. Standing on either side of the stage while each panelist spoke they held up a sign reading “Oh Really,” and then turned it over to show “But, I’m not angry,” any time self-serving statements were frequently made.15 Gallerist Holly Solomon, for instance, advised women “to use their natural attributes to get ahead . . . like their breasts.”16 Here the Guerrilla Girls invoke the efforts of feminist predecessors from the late 1960s and early 1970s, such as the Women’s International Conspiracy from Hell’s (WITCH) “zap actions,” including “Up Against Wall Street” (Halloween, 1968) where women “hexed” banks and brokerage firms, resulting in a 5-point stock market decline.17 Ad Hoc Women artists didn’t just picket the Whitney in 1970, but also faked press announcements and tickets and strew eggs and unused menstrual pads during a museum opening, in addition to projecting images of women’s artwork on the building’s exterior.18 Marcia Tucker explains that these types of feminist actions engage in the carnivalesque, where women “. . . curse, rant and rave and make fun of and mimic whomever and whatever they want, themselves included,” ultimately exposing the transgressions of those in power.19 More importantly, engendering laughter and the absurd cements a bond with an audience that would rather be in on the joke than be its subject, and offers a significant moment Dearest Eli Broad, 2008 where ideological transformation can occur.20 In the 1970s, feminist activist art was viewed as a means of mutual exchange between artists and audience, which stimulated the development of numerous alternative education programs for women artists. For example, in 1970 Judy Chicago established the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State and Chicago, Sheila de Bretteville and Arlene Raven founded the Feminist Studio Workshop in 1973 in Los Angeles.21 These student-driven programs armed participants with feminist ideology, histories of women and their representation, and tactics that could be used to develop art and activist campaigns. Now that the Guerrilla Girls have twenty-seven years of expertise under their collective belt, they continue this tradition by sharing their own experience in one-day activist workshops. In the two-day Chicago workshop the Guerrilla Girls first poll participants on their primary topic interests and then form groups of those who wish to work on similar themes. Once the subject is determined, images are developed and then critiqued multiple times before the final project is executed. In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, young women developed a campaign on body image where an archaeologist discovers the “ancient” tradition of the Brazilian wax; in Kentucky, a workshop addressed the abstinence pledge many teenagers are asked to take. In October 2011, students in a papermaking workshop at Columbia College Chicago paid homage to the Guerrilla Girls by producing a series of posters on abaca paper (made from the banana tree), which investigated social and environmental conditions in Chicago, such as air quality and high levels of autism.22 Although they only remain in any specific community for a short time, the Guerrilla Girls’ emphasis on providing tools and expertise in the subversive uses of information conveys skills that the participants adopt for themselves, but may be shared with others. Such methods of generating dialogue, debate, and action are much more difficult to measure than the more immediate impact of posters, but the Guerrilla Girls’ “small exchanges” become global networks of resistance that are established across communities over time.23 Building on a long history of feminist collaboration, the Guerrilla Girls have created a unique and important paradigm for activist art practice. Although their posters are found in institutional collections, they are not represented by any commercial gallery nor do they promote individual women artists through curated exhibitions despite numerous offers made to them to do so.24 This barrier permits them to occupy a powerful space where they move fluidly between margin and center, maintain pressure, and motivate others to take up the cause for ending oppression against women, all the while giving us a good laugh. I am very grateful to the Guerrilla Girls, Frida Kahlo and Kathe Kollwitz, for their generous responses to my many questions. 27 Fig. 5: Posters on Montreal streets, 2009 Figs. 6, 7: Banners in Belfast, 2009 Fig. 8: Lady Pink, Brick Girl Crying, 2001, Acrylic on canvas Figs. 1,2,3,4: Posters on New York streets, 1980’s 28 Guerrilla Girls, Graffiti, and Culture Jamming in the Public Sphere by Kymberly N. Pinder, Ph.D., School of the Art Institute of Chicago In 1985 a small group of women artists in New York formed the Guerrilla Girls in direct response to the curator Kynaston McShine declaring that any artist not in the exhibition “An International Survey of Painting and Sculpture” at the Museum of Modern Art should re-examine his career. In most documentary photographs the Guerrilla Girls’ large posters, including exhibition announcements, were the first to obscure most of the existing street art on the walls (Fig. 1).3 Layers of gallery ads are discernible around and beneath the Guerrilla posters with graffiti writer’s whips and letters leaping out from behind them like colorful baroque frames. The Guerrilla Girls were not only entering into an aggressive dialogue with the artworld establishment, but also with the street artists whose public forum they were appropriating. The latter conversation was purely circumstantial: these feminist activists were not disenfranchised youth struggling against a bleak, post-industrial plight. They were majority middle-class artists of varying ages trying to raise awareness in the cheapest and most effective manner possible. In the 1980s, their protest posters utilized a space that contained many political transgressors, outsiders, and “culture jammers” all of whom were railing, in their own way, against “The Man.” As graffiti scholar Ethel Seno writes, “It is vital to understand how the uncommissioned intervention is a reflex against the hegemony of public space by the interests of the law over the psychological well-being of the many.”4 Like graffiti writers and punk posterers, the Guerrilla Girls were also “claiming territories and inscribing their otherwise contained identities on public property.”5 Within contested public spaces these posters joined the fray within the visual landscape of the Lower East Side. More often than not the documentation for these posters presents them as isolated graphic designs in a textbook or article. In examining the few surviving images of the early Guerrilla Girls posters in situ, the way they would have been seen in the street engages the urban art history of these posters (Figs. 2, 3). For example, to remain in the visual conversation of a site already crowded with posters, including those by the Guerrilla Girls, taggers like THOR, BUSTER, SLIM, and a handful of stencilers moved to the façade’s outer architectural posts that frame the recessed wall of the building. The raised striations here were unfriendly to wheatpasting so the taggers employed the horizontal bands as marquees or banners for their names. A large, heavily detailed stencil of a skeleton on top of SLIM’s tag offers a visual pun worthy of Guerrilla wit. This framing gave the taggers the odd position of both dominators and caretakers of the art posters. The jockeying for space among street artists, galleries, and feminist voices is a map of SoHo’s gentrification in the mid-80s. Ironically, legibility and identity have a curious relationship in these SoHo photos. The taggers’ names are obscured by their own “wild style,” and by the gallery posters in which the names of the galleries and their exhibiting (all male) artists are large and clear. The real names of the Guerrilla Girls are not represented. This visual relationship among names highlights the complex interplay between subversion and anonymity that both the Guerrilla Girls and street artists deploy in their urban interventions. In another street image showing the Guerrilla Girls poster, On Oct. 17 The Palladium will apologize to women artists—both protest 29 signage and exhibition announcements—among layered clutter makes the very small posters the most legible and complete text on the wall. The only legible texts are two looming tags: ROCK and CATCH. In street art culture, there are strict codes concerning when and why one artist may go over another’s work. Gestures of dominance via tagging, postering, or painting completely over a peer’s work could incite violence. How a piece disappears is crucial. Graffiti blasters—city trucks that power-wash graffiti off walls—are one thing, someone else’s tag or poster is another matter entirely—it is a public challenge. In a third documentary photograph, three Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? posters remain intact and one poster has been ripped in half but retains its text (Fig. 4). The tag MAX.K. in blue spray paint obscures the Ingrés nude with gorilla mask. Lines of the blue tag appear both under and over the paper fragments recording the chronology of this set of defiant gestures. At least four writers responded to these posters on their wall.6 As KANE explains, “As a location accumulates more tags by more participants, it generates momentum and conversation among the graffiti community. It becomes a goal to see how many people can participate before it inevitably gets erased. ‘How long can we live in this ephemeral moment together?’ The Guerrilla Girls’ posters over these visual conversations are equivalent to the police shutting down a great party. Hegemony is restored.”7 On the contrary, the Guerrilla Girls posters just joined the party. One has clearly covered MAX.K’s tag, and he subsequently returned to tear off the poster and restore some of it with another dose of aerosol. The writer in red, the creator of the white paste-up or small poster, and GAERY POSER also responded directly onto the posters themselves. The latter tagger was clearly taking advantage of a surface amenable to a Sharpie, while one can only speculate why the red tagger “respected” the Guerrilla poster and tagged beneath it, taking care not to get too much of his/her serif onto its lower edge. In another “installation shot” of these two posters, the dialogue is literal in that someone responded to the question posed with “No, they just have to make worthy art.” In a darker ink, “YO” was written boldly on the nude’s buttocks.8 The poster attacked sexism and sexists struck back. As seen here, graffiti writers were also beginning to poster or “flypost” in the 80s. Spray-can artists were turning to alternative methods such as stickers and stencils. In their book History of Graffiti, Roger Gastman and Caleb Neelon explain “the poster was in effect . . . a simple, relatively low-risk way to get up.”9 According to graffiti lore, in 1983 writers DJ NO and TESS of X-MEN created posters to combat 30 the advertisements that someone was specifically placing over their tags: “The originals were done by hardcore, all-city, ink-and paint-stained writers, DJ NO and TESS X-MEN—and because of a beef!”10 Other writers, like the well-known Shepard Fairey, have used posters to reach a larger and more diverse audience. As KANE describes: [T]heir aesthetic wasn’t exclusionary to the graffiti community. It was sans-serif type that was meant to be legible by the masses. Their campaign at the time was equivalent to what a large marketing agency would need 100s of people to execute nowadays. There’s also an extra layer of subversion in the act, when it doesn’t look like ‘graffiti’. . . . There’s a lot of privilege and oppression that arises when using graffiti practices to one’s own promotion, but simultaneously distinguishing and separating the content that creates a cultural distance from graffiti. A person wheat pasting a poster may get as little as a ticket if caught by the authorities. A person caught spray painting can potentially wind up at Guantanamo Bay under the Patriot Act.11 Because the Guerrilla Girls postered in the arts district, their activist moves jive very much with the street art of Keith Haring or the clever, enigmatic, often indicting prose or “speech acts” of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Barbara Kruger circa 1982.12 All three artists strategically placed their street interventions in SoHo, and in parts of Manhattan. Historians and writers still argue whether Basquiat’s simple texts in black spray paint, largely without any ornamentation or imagery, had more affinities with advertising than graffiti. The artist and his collaborators Al Diaz and Shannon Dawson created the SAMO tag that sometimes addressed issues of art-world inclusion and consumerism. Kollwitz remembers seeing SAMO’s work at the time and finding it poetic as well as sometimes opaque.13 In December 2009 the Guerrilla Girls re-entered the conversation between fine art and street art by creating their first facsimile of a gray brick wall covered in brightly colored quotations scrawled in graffiti-like fonts entitled Disturbing the Peace in Montreal that were large vinyl posters put up around Montreal, Québec, to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of a mass killing at l’École Polytechnique in which a man who hated feminists shot and killed fourteen female students (Fig. 5). The Guerrilla Girls wrote: “We decided to focus on the history of hate speech against women and feminists, from the Ancient Greeks to Rush Limbaugh. We’re bothered that it has always been OK to make denigrating public statements about women, and shocked by the violence and abuse this language continues to provoke.”14 For them, simulating graffiti represented public and uncensored speech: “It seemed interesting to have the quotes ‘scrawled’ on a wall, the way hate speech often is. This poster is also one of the few the Guerrilla Girls have done that has no headline.”15 In 2010 they brought attention to the exclusionary practices of art schools and museums in Ireland with an interactive installation entitled Guerrilla Girls All Ireland Project at no. 76 John Street in Kilkenny (Figs. 6 and 7). The artists installed a vinyl sheet of a bright pink brick wall with handwritten and spray painted phrases and statistics about the gender imbalance in Ireland’s art schools and galleries. On the other side of the gallery was a blank wall in which visitors were encouraged to write their own responses. In other installations, the wall has been a blackboard on which to write.16 With these posters graffiti has become a trope functioning as both a subversive brand and a vehicle for hate speech. As the earlier posters obscured and sparred with actual tags, current posters replicate the open forum of the street to criticize offensive public discourse in another urban context. A quotation about acknowledging misogyny below the frame of the fake graffiti wall and the group’s web address are the de facto didactic headline. The Guerrilla Girls’ brand functions as synecdochically as the graffiti graphics. Inside the galleries, visitors’ own writing on the walls mirrors actual taggers, “talking back” and taking back ownership, albeit fleeting, of a contested space. And where do actual female graffiti writers enter into this “found” dialogue between street art and feminist poster “bombing”? While most writers do not make politicized work, more women graffiti artists do than their male peers. Tags like LADY PINK, DIVA and FEMME9 often reflect the goals of “getting up” to represent skills equal to or better than the men. LADY PINK or PINK, one of the first well-known female writers who started tagging in the late 70s, helped the Guerrilla Girls poster in SoHo. Her description of that time sums up the dichotomy between the two worlds she inhabited—the street and the gallery: I wasn’t a Guerrilla but I knew them. . . . I volunteered to hang an exhibit at The Clocktower and to go postering for them at night since I had that kind of experience. . . . The regular poster spots were hit but due to the crowding of writers and posters downtown everyone went over each other. The writers didn’t even notice that the Guerrilla Girls existed. Only a small minority of graff writers were involved in the “Art scene” and we were mostly retired and not active. . . . These were different worlds, the very well-bred artsy ladies and the rough underground world of boys and subway vandals. Their posters were considered a blank canvas to tag on. I happen to be a cross-over, being female, artsy and a vandal.17 The sexism PINK experienced as a writer raised the feminist consciousness that drew her to the Guerrilla Girls: “I went piecing deliberately with different groups so that everyone could see I could actually paint this stuff and not having some guy do it for me” (Fig. 8).18 Her constant negotiations with obscuring and revealing her identity parallel similar exercises in invisibility and power that the Guerrilla Girls have deployed throughout their careers. Using her real name masked her graffiti identity among the “artsy ladies,” while she sought visibility among male writers for street credibility. The collective name and gorilla masks have also offered the Guerrilla Girls a freedom of movement between multiple spheres. Other female writers approached their minority status as women differently. CLAW, another early writer who now designs and sells CLAW clothing and jewelry, remarks simply, “I was a feminist before I ever picked up a can of paint—I painted because of THAT. . . . I didn’t attach a “Miss” or “Lady” to my name, nor did I paint with tons of hearts or girly flair. I wanted to bomb, so I did it just like anyone else. Being a woman, of course feminine overtones would shine thru [sic] once in a while.”19 A brief survey of websites and blogs by young female artists and collectives results in numerous citations of the Guerrilla Girls.20 The Guerrilla Girls’ public lectures and their books geared towards lay readers have enabled many young women artists today to learn about these activists while growing up, as did graffiti artist CHICAGOLOE: “I learned about the Guerrilla Girls in my high school art history class; the only art class offered at my high school. They are very impressive. They went about their business by using a great strategy forcing the public to acknowledge the fact that they were equal.”21 Street artists and the Guerrilla Girls continue a legacy of subversion in multiple spheres into the new millennium and the art world is acknowledging their pivotal roles in art history as culture-jammers, consciousness-raisers, and tastemakers. In the summer of 2011 the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles mounted a historic exhibition “Art in the Streets” that drew record crowds, and in 2010 art by the Guerrilla Girls was exhibited in the Whitney Biennial and in the significantly titled exhibition “Contemporary Art from the Collection” at the Museum of Modern Art in honor of the Girls’ twenty-fifth year in business—or, as they would say, in radical monkey business. I would like to thank Käthe Kollwitz and Frida Kahlo for sending me the installation documentation in this essay. 31 End notes Not Ready to Make Nice 1. Examples of past feminist activist groups can be found in the recent documentary, !Women, Art, Revolution, directed by Lynn Hershman Leeson, 2011, Hotwire Productions. 2. Phone conversation with the author, August 11, 2011. 3. This excerpt is from a press release that was mailed to a select group of people following the debut of the first posters in May 1985. Email communication between the author and the Guerrilla Girls, 12/27/11 4. Conversation with Jane Saks, November 10, 2011. 5. Oral history interview with Frida Kahlo and Kathë Kollwitz (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2008), 7) 6. Phone conversation with the author, September 21, 2011. 7. The exhibition Not Ready to Make Nice features an installation of some of the most provocative love letters and hate mail the Guerrilla Girls have received since their formation. Some of these letters are so dear to the collective that they have held onto them for decades for encouragement and inspiration. As for the hate mail, the collective often jokes that much of it is the unfortunate result of the writer’s lack of a sense of humor. Conversation with the author, October 19, 2011. 8. For a thorough discussion of the key women’s 9 collectives/centers in Chicago, see Joanna GardnerHuggett, “Cultural Transformation through Collective Participation in the Women Artists’ Cooperative: Artemisia, ARC and Woman Made Galleries in Chicago,” in Beyond Feminist Citizenship, ed. Sasha Roseneil (Palgrave Press, 2012). 10. The Guerrilla Girls’ research for the Chicago piece, both the data they collected from museum websites and from what was on view in the museums themselves, was conducted during multiple visits in October 2011. 11. Phone conversation with the author, September 21, 2011. 13. Oral history interview with Frida Kahlo and Kathë Kollwitz, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2008, 61. 14. The Guerrilla Girls delivered the SAIC commencement speech in May 2010. The transcript can be found at www.guerrillagirls.com/books/SAIC.shtml, last accessed on December 15, 2011. 15. The group spent a week in October 2011 working with Columbia College students in several different disciplines. They openly shared their techniques in creating effective campaigns, helped students identify their own issues to tackle and demonstrated how activism can be sustained over a long period of time. The Feminist Roots of the Guerrilla Girls’ “Creative Complaining” Elizabeth Hess, “Guerrilla Girl Power: Why the Art 1. World Needs a Conscience,” in But is it Art? The Spirit of Art as Activism, ed. Nina Felshin (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995), 313. Mira Schor, “Backlash and Appropriation,” in The 2. Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact, eds. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1994), 249. See Helen Molesworth, “House Work and Art 3. Work,” October 92 (Spring 2000): 73. Email correspondence with Frida Kahlo and Käthe 4. Kollwitz, October 11, 2011. For a history of women artists’ cooperatives see Judith K. Brodsky, “Exhibitions, Galleries and Alternative Spaces,” in The Power of Feminist Art, 104–119. Anna C. Chave, “’The Guerrilla Girls’ Reckoning,” 5. Art Journal 70 (Summer 2011): 106, n. 21. 32 Carrie Rickey, “Writing (Righting) Wrongs: Feminist 6. Art Publication,” in The Power of Feminist Art, 126–127. Email correspondence with Frida Kahlo and Käthe 7. Kollwitz, October 11, 2011. Chave, “‘The Guerrilla Girls’ Reckoning,”111. 8. Patricia Hamilton quoted in Eleanor Heartney, 9. “How Wide is the Gender Gap?,” ARTnews 86 (Summer 1987): 142. 10. Email correspondence with Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz, October 11, 2011. 11. The Guerrilla Girls, Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls (NY: Harper Perennial, 1995), 46–47. 12. Garrard, “Feminist Politics: Networks and Organizations,” in The Power of Feminist Art, 90. 13. Sarah Meller, “The Biennial and Women Artists: A look back at Feminist Protests at the Whitney,” May 3, 2010, accessible at http://whitney.org/Education/ EducationBlog/BiennialAndWomenArtists, last accessed on December 4, 2011. 14. Oral history interview with Guerrilla Girls Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz, Jan. 19–Mar. 9, 2008, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. 15. Josephine Withers, “The Guerrilla Girls,” Feminist Studies 14 (Summer 1988): 287. 16. The Guerrilla Girls, Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls, 42. 17. Garrard, “Feminist Politics,” 91. 18. Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 160. 19. Marcia Tucker, “Attack of the Mutant Ninja Barbies,” in Bad Girls, exhibition catalogue (NY and Cambridge: New Museum and MIT Press, 1994), 20. 20. Tucker, “Attack of the Mutant Ninja Barbies,” 20. 21. Tucker, “Attack of the Mutant Ninja Barbies,” 24. 22. See Laura Meyer, ed. A Studio of their Own: The Legacy of the Fresno Feminist Experiment (Fresno: The Press, California State University, 2009). 23. Phone conversation with the author, October 28, 2011. Regarding the Columbia College workshop, email correspondence with Melissa Potter, November 4, 2011. 24. Phone conversation with the author, October 28, 2011. 25. In 1985 the Guerrilla Girls curated an exhibition of approximately 100 women artists at the Palladium in New York City. While they felt the event staged an important intervention they decided never to curate a show of women artists again. “We represent all women artists, not a selection of them.” Oral history interview with Guerrilla Girls Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Guerrilla Girls, Graffiti, and Culture Jamming in the Public Sphere Guerrilla Girls, Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls 1. (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 89. This vulnerability and ephemereality of the posters 2. made the Guerrilla Girls turn to the bus billboards which also took their message into other areas of Manhattan just as the subway cars had done for the local graffiti writers spreading their tags across the five boroughs. The internet has now usurped much of this access. In response to considering how they used postering and the forum of the street and its walls to communicate to large audience, Frida stated, “What is the street really? At first we did use the real street to get our message out to the most people but now, the internet is the street. We can reach so many more people twenty-four hours a day through our website. The street and access continue to change.” Author’s interview with Käthe Kollwitz and Frida Kahlo, October 19, 2011. In his book, Vitriol: The Street Art and Subcultures of the Punk and Hardcore Generations (Oxford: U. of Mississippi, 2011), David Esminger also notes how the internet with its “virtual street corners teaming with so-called friends [and] digital flyers” has supplanted the postering on poles and walls in the urban space. . . ,” 7. Ethel Seno, ed., Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned 4. Urban Art (Köln: Taschen, 2010), 22. Tricia Rose, “A Style Nobody Can Deal With: Politics, Style in 5. the Postindustrial City in Hip Hop” in Andrew Ross and Tricia Rose, eds., Microphone Fiends: Youth Music and Youth Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), 71. I say “their” wall because a wall rich with tagging signals a 6. popular and active forum in which marks and counter marks are visual chats and spars occurring over days and even months. KANE’s email correspondence with author, October 25, 7. 2011. Quite a bit can be said about this interjection here. In the 8. 1980s, “yo” was a black urbanism synonymous with black male self assertion and hip hop culture. Within the bilingual context of SoHo, “yo” also means “I” in Spanish. Therefore, in this particular image battle, a black and/or Latino id marks, “disses” or “owns” Ingres’s white ass and that of the posterer. Roger Gastman and Caleb Neelon, The History of American 9. Graffiti (New York: HarperCollins, 2010), 382. 10. DJ NO quoted in Gastman, 382. 11. KANE’s email correspondence with author, October 21, 2011. It should be mentioned that the Guerrilla Girls have had no serious run-ins with authorities, whether in masks or not, in their decades of postering. 12. Diedrich Diederichsen, “Street Art as a Threshold Phenomenon” in Jeffrey Deitch, ed. Art of The Streets (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art of Los Angeles and Rizzoli), 285. 13. Basquiat was not alone; in the 1980s in San Francisco the writer APOLLINAIRE painted large portrait heads with speech bubbles questioning the art establishment in underpasses. “Museums represent the mummy of a culture that has long since been dead.” Gastman and Neelon, 381. 14.http://www.guerrillagirls.com/posters/Montreal.shtml,last accessed December 11, 2011. 15. Email correspondence with Käthe Kollwitz, October 26, 2011. 16. Email correspondence with Käthe Kollwitz, October 25, 2011. 17. Quoted in Nicholas Ganz, Graffiti Women: Street Art From Five Continents (New York: Abrams, 2006), 13. 18.Ibid. 19. CLAW’s email correspondence with author, October 25, 2011. 20. This is a topic for yet another essay. For example, the female street artist Princess Hijab compares her “hijabization” of exposed bodies used in advertisements in and around Paris to the feminist campaigns by the Guerrilla Girls. Working anonymously, Hijab has been painting burkas on ad imagery since 2006. Although she has recently revealed that she is not Muslim, she did describes herself as racially marginalized in French society (http:// bitchmagazine.org/article/ veiled-threat). Some are less committed: one website called G.A.G. (Guerrilla Art Girls) that gives instructions in making decorative magnets or environmentally conscious moss graffiti bombs for the urban landscape clarifies their relationship to the Guerrilla Girls: “We are not much interested in being proponents of particular politics, but rather in making people smile. We are not radical feminists [“radical feminists” links to Guerrilla Girls in Wikipedia. org] out to prove anything, but want to inspire curiosity and spread cheerfulness, hopefully until you puke,” http://guerrillaartgirls. blogspot.com/2010/05/moss-graffiti-inspiration.html, last accessed on December 11, 2011. The Riot Grrl movement that was original female musicians then became involved in feminist zines also cites the Guerrilla Girls as inspiration. For more see Nadine Monem, ed., Riot Grrl: revolution girl style now! (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007). 21. CHICAGLOE’s email correspondence with author, October 19, 2011. Exhibition Checklist Artworld Posters of 1980’s and 1990’s, Installation of selected street posters. Mixed media installation, digital prints on paper These Artists, 1985, 17"x 22" These Galleries, 1985, 17" x 22" Museums,1985, 17" x 22" 1986 Report Card, 1986, 22" x 17" Women Earn 2/3, 1986, 17" x22" Advantages of Being A Woman Artist, 1988, 17" x 22" Racism and Sexism, 1989, 17" x 22" Token Times,1995, 17" x 22" Beyond Posters of 1980’s, 1990’s, Installation of selected street posters and projects. Mixed media installation The Anatomically Correct Oscar, 2002-2012 First appeared in The Nation magazine, followed by stickers, posters, billboards and large-scale banners. Digital print on fabric 7’6” x 18’ Estrogen Bomb, 2003-2012 First appeared in the Village Voice, followed by stickers and posters. Digital print on fabric 7'6" x 7'6" Benvenuti alla Biennale Femminista, 2005–2012 First shown at the 2005 Venice Biennale. Digital print on fabric 11’6” x 8’ Pop Quiz, 1990, 17" x 22" Traditional Values on Abortion, 1992, 17" x 22" Missing in Action 1992, 17" x 22" What’s the Difference Between a Prisoner of War and a Homeless Person?, 1992, 22" x 17" Newt, 1995, 17" x 22" 10 Trashy Ideas About the Environment, 1996, 12" x 9" Battle of the Sexes: Project for the New Yorker, 1996, 17" x 22" Where are the Women Artists of Venice?, 2005–2012 First shown at the 2005 Venice Biennale. Digital print on fabric 11'6" x 8' Love and Hate Letters, 1980’s to present Installation of reproduced mail and email letters sent to the Guerrilla Girls. Mixed media installation Unchain the Women Directors / Hay Que Quitar Las Cadenas a Las Mujeres Directores, 2006-2012 First appeared as billboard in Hollywood, followed by large-scale banners in Bilbao, Spain and Mexico City. Digital print on fabric 7'6" x 18' Dearest Art Collector in English, Greek and Chinese, 1986-2012 First shown as a street poster, followed by placards in Shanghai and large-scale banners in Athens. Digital prints on paper 24" x 36" Do Women Have to be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum?, 1989-2011 Originally shown on NYC busses in 1989, followed by posters, large-scale banners and billboards. Current version has statistics from 2011. Digital print on fabric 8' x 18' The Birth of Feminism Movie Poster, 2001- 2012 First appeared in Bitch magazine, followed by posters and large-scale banners. Digital print on fabric 11'6" x 7'6" The Future for Turkish Women Artists, 2006–2012 First shown in Istanbul Modern Museum, Turkey. Digital print on fabric 6' x 9' Horror on the National Mall: 2007- 2012 Appeared as a page in the Washington Post, April, 20, 2007, followed by posters and large-scale banners. Digital print on fabric 8' x 5' Museums Unfair to Men/Museums Cave In To Radical Feminists, 2008–2012 Picket signs and photographic documentation of collaborative action with the Brainstormers at the Bronx Museum and Chelsea art galleries, New York. Mixed media installation Dearest Eli Broad, 2008 Action photo of posted letter written by artists at the Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Panel 36” x 24” I’m not a feminist, but…, 2009-2012 One of three large scale banners for the Guerrilla Girls’ All-Ireland Tour developed for Millennium Court Art Center, Belfast, then travelled to Cork, Dublin and Kilkenny. Interactive wall installation with visitor contributions Irish Toast, 2009-2012 One of three large-scale banners for the Guerrilla Girls All-Ireland Tour developed for Millennium Court Art Center, Belfast, then travelled to Cork, Dublin and Kilkenny. Digital print on fabric 9.5’ x 14' Disturbing the Peace / Troubler le Repos, 2009–2012 First shown at the Gallery of the University of Quebec and on the streers of Montreal. Digital print on fabric 7'6" x 10' 6" Chicago Museums: Time for Gender Reassignment, 2012 Digital print on fabric Panel 11’6” x 14’ Snap a Pic with the Guerrilla Girls, 2012 Photographic cut-outs of the artists The Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art, 1998 Published by Penguin Panel 24" X 36" Bitches, Bimbos and Ballbreakers: The Guerrilla Girls’ Guide to Female Stereotypes, 2003 Published by Penguin Panel 36" x 24" The Guerrilla Girls’ Art Museum Activity Book, 2004, 2012 Published by Printed Matter Panel 36" x 24" The Guerrilla Girls’ Hysterical Herstory of Hysteria and How It Was Cured, From Ancient Times Until Now Installed as ten 11" x 22" panels 33 Acknowledgments The Columbia College Chicago Department of Exhibition and Performance Spaces, Ellen Stone Belic Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in Arts and Media, and the A+D Gallery wish to thank the following individuals and organizations for their assistance: Student Affairs, Critical Encounters, Ben Bilow and Creative Services, Brandy Savarese, Student Loop, The Chronicle, Media Relations, the Columbia College Chicago Library and the Office of the President for the support of this year-long initiative; the Columbia College Chicago Art + Design Department, Book and Paper Center, and the Department of Arts, Entertainment and Media Management for the production of student workshops; and especially to the Guerrilla Girls for enthusiastically agreeing to embark on a year-long, multifaceted, student-centered project with Columbia College Chicago and for pouring their tireless energy, vision, and humor into Not Ready to Make Nice. We are proud to show this body of work on Columbia’s campus and in the city of Chicago. colum.edu This exhibition is partially supported by The Department of Exhibition and Performance Spaces, a division of Student Life, entirely supported by the Student Activity Fee, the Leadership Donors of the Ellen Stone Belic Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media at Columbia College Chicago, Chicago Foundation for Women, the Art + Design Department and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. All images are courtesy of the Guerrilla Girls unless otherwise noted. Copyright © 2012 Guerrilla Girls Copyright © 2012 Columbia College Chicago ISBN: 0-929911-43-1 34 35 March 1 – April 21, 2012 a+D AVERILL AND BERNARD LEVITON A+D GALLERY 619 SOUTH WABASH AVENUE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60605 312 369 8687 Colum.edu/adgallery Glass Curtain GALLERY 1104 S. Wabash Avenue, First Floor CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60605 312 369 6643 colum.edu/deps August 25 – December 15, 2012 23 Essex Street Beverly, Massachusetts 01915 montserrat.edu/galleries 36