Ethiopia: An Alternative Approach to National Development

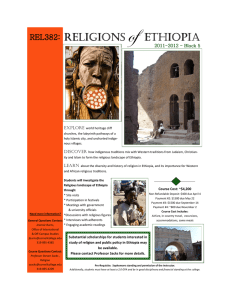

advertisement