T w Traditional forms of agriculture : unexpected degree of diversity, time-honoured principles

advertisement

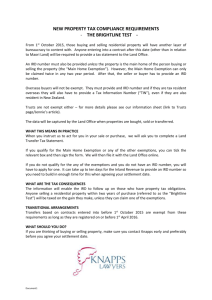

Sheet n°301 - June 2008 w Traditional forms of agriculture : unexpected degree of diversity, time-honoured principles light of principles emphasizing self-sufficiency, or even sheer survival, as opposed to cash cropping, manual labour as opposed to an extreme level of mechanization, extensive practices as opposed to intensification. A more caricatural image holds up mixed cropping, whether or not associated with livestock rearing, in a sharp contrast to one of vast prairies of cereal monoculture. However, this conventional, rather simplistic image touches only the tip of the iceberg of the enormous diversity of traditional agricultural systems that exist. They may now make up only a tiny proportion of the farmed surface area of the world, but they are remarkable in their complexity and their ability for adaptation to restricted and harsh environments. Two IRD researchers, working jointly with scientists from both national and international organizations, made highly detailed surveys of these agricultural methods, some dating back several millennia. They have now published a book setting out the most extraordinary examples. This work, with its cultural and historical flavour, is more than just a straightforward selection of ancestral farming techniques. It also evokes how such forms of agricultural are embedded within each society that elaborated them. © IRD / Marc Pouilly he general public T often regards traditional agriculture in the Beating wheat in the Torotoro region (Bolivia). The modern agriculture that is sometimes taken to be the “conventional” one is daily gaining ground over socalled traditional or extensive forms of farming practised for several thousand years by rural populations who in some cases live on the fringes of industrial society. These forms of agriculture are often highly idiosyncratic and take up only a tiny portion of the Earth’s total cultivated surface. Yet they stand out owing to their ability to adapt to a constantly changing natural environment and to the diversity of farming practices they adopt. It is difficult to draw up an exhaustive list of what are often atypical methods. Nevertheless, a book co-written by IRD researchers and their partners presents no less than 65 examples scattered over all the continents. This work gives and idea of the sheer imagination, adaptability, endurance and skills of observation of human communities who, in the most unyielding environments or the harshest climates, have managed to find a solution for survival through a complete mastery of plant cultivation. Today, some of these practices persist only in a particular area of the world. Others, like traditional agriculture practised in marshy areas, are found in similar form in the different continents. Thus, the hortillonage system in Europe and Asia shows many similarities with Mexican chinampas, the Andean camellones and the raised, drained taro fields of the western Pacific. These types of agriculture involve a network of canals and raised plots of land on which food cropping can be practised. But whereas such systems in Picardy (France) -the hortillonagesare steadily dying out, their counterparts are developing spectacularly on the coasts of countries open to international markets, like Indonesia or Thailand. Particular climatic or population stresses often push farmers to use ingenious methods. In Tunisia, lagoonal bars, unsuitable for agriculture owing to salt content and sand devoid of the minerals essential for plants, are harnessed by local people to produce vegetables and cereals (potatoes, onions, peppers, squash and related produce, maize and so on). With no active irrigation, rainfall accumulates in the layer of sand men bring on their backs and mix with manure. That water is then taken down to plant root level by the beating of the tides. On the Canary island Lanzarote, which receives annually no more than 150 mm of rainwater, farming seems like an impossible challenge. Yet it is on this island that one of Spain’s most repu- Institut de recherche pour le développement - 213, rue La Fayette - F-75480 Paris cedex 10 - France - www.ird.fr Retrouvez les photos de l'IRD concernant cette fiche, libres de droit pour la presse, sur www.ird.fr/indigo CONTACTS : ERIC MOLLARD Unité de recherche Dynamiques socioenvironnementales et gouvernance des ressources Address : IRD BP 64501 34394 Montpellier cedex 5 France Tel : + 33 (0)4 67 63 69 81 eric.mollard@ird.fr ANNIE WALTER Unité de recherche Caractérisation et contrôle des populations de vecteurs annie.walter@ird.fr REFERENCE : Agricultures singulières Éditeurs scientifiques : ERIC MOLLARD, ANNIE WALTER Editions IRD, 2008, 344 p ted wines is produced. Remarkably, the vines do not desiccate in the sun, but this is because of the growers’ ingenuity. They plant the vines one by one in conical hollows they cover over with volcanic ash and lava stones. Scientific studies have shown that this protective layer is a means of holding eight times more water than bare soil and decreases evaporation by 92% when its thickness reaches 10 cm. Low walls protect the year’s foliage and the bunches of grapes from the trade winds. Contrary to a widespread idea, traditional agriculture is not synonymous with an archaic way of doing things. This is illustrated by the highly elaborate system of mulberry dykes still seen in southern China. This agricultural practice combines market gardening, aquaculture and cultivation of mulberry used as food for silk worms, and is probably one of the best examples of integrated agriculture where none of the constituent elements can be envisaged independently from the others. One of the probable characteristic elements common to each of these singular forms of agriculture, whatever their degree of complexity, is the need for the collective work of the members of the community who practise it. Moreover, account must be taken of the effort, financial investment and multiple functions these types of agriculture represent for the people concerned. It remains, however, that the right level of adaptation achieved between the environment, humans and a particular type of agriculture does not always last. Indeed the environment never ceases to change under human activity in general and agriculture in particular. Persistence of these techniques over time also comes up against population growth and structural changes in the societies that set them in place. It is therefore difficult to transpose the practices involved. They are based at any given moment entirely on a balance between a type of environment and a type of society. But in spite of their extraordinary nature and the fact that they constitute only a tiny proportion of all agricultural systems, they still stand as a source of inspiration and lessons for the development of agriculture. Grégory Fléchet - DIC Translation - Nicholas Flay 1. The research carried out was conducted with contributions from researchers from CIRAD, the CNRS, the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, the Center for International Forestry Research (Indonesia), the Institut français d’études andines (Peru), the International Water Management Institute (Ghana), the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul and from the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (Brazil). KEY WORDS : Traditional agriculture, adaptation, natural environment VINCENT CORONINI +33 (0)1 48 03 75 19 presse@ird.fr INDIGO, IRD PHOTO LIBRARY : DAINA RECHNER +33 (0)1 48 03 78 99 indigo@ird.fr www.ird.fr/indigo On the left, hortillonnage in Thailand given over to coriander growing, between an asparagus crop and a rice field. On the right, on the isle of Lanzarote, in the Canaries, each vine planted at the bottom of a conical hollow is protected by a low crescent-shaped wall. Grégory Fléchet, coordinator Délégation à l’information et à la communication Tél. : +33(0)1 48 03 76 07 - fax : +33(0)1 40 36 24 55 - fichesactu@ird.fr © IRD / Alain Gioda PRESS OFFICE : © IRD / Eric Mollard Sheet n°301 - June 2008 For further information