U V NIVERSITY

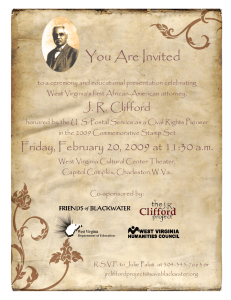

advertisement