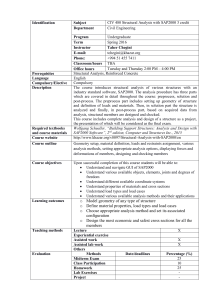

SAP2000 ® Integrated Finite Element Analysis

advertisement