Relationship between placental histologic features and

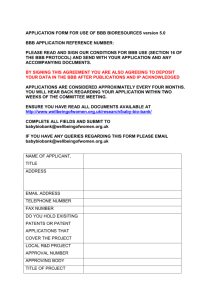

advertisement

Relationship between placental histologic features and umbilical cord blood gases in preterm gestations Carolyn M. Salafia, MD, . . . . . . f Victoria K. Minior, BS," Jos~ A. L6pez-Zeno, MD, g S. Scott Whittington, MS, c' f John C. PezzuUo, PhD, d' " and Anthony M. Vintzileos, MD b Farmington, Connecticut, New Brunswick, New Jersey, Washington, D.C., and Ponce, Puerto Rico OBJECTIVE: Our purpose was to test the hypothesis that placental histologic lesions reflect abnormal placental respiratory function in preterm gestations. STUDY DESIGN: A retrospective study of preterm deliveries from 22 to 32 weeks revealed 431 patients with umbilical venous or arterial blood gas values. Excluded were stillbirth, multiple gestations, placenta previa, maternal medical diseases, and fetal anomalies. Charts were reviewed for principal indication of delivery, diagnosis of labor, and mode of delivery. Blood gases were studied within 10 minutes of delivery on a model 178 automatic pH analyzer (Coming Med, Boston). Placental data included uteroplacental vascular lesions and related villous lesions, lesions of acute inflammation, chronic inflammation, and coagulation. Contingency tables and analysis of variance considered p < 0.05 as significant. RESULTS: Mean - SD umbilical vein pH was 7.36 -+ 0.07 (range 6.94 to 7.56) and umbilical artery pH was 7.30 +_ 0.08 (range 6.83 to 7.55). Increasing severity of uteroplacental thrombosis, villous lesions reflective of uteroplacental vascular pathologic mechanisms, avascular villi, histologic evidence of abruptio placentae, 'chronic villitis, and increased circulating erythrocytes were associated with decrease in umbilical vein and artery pH, increase in umbilical vein and artery Pcoa, and decrease in umbilical vein and artery Po2. Histologic evidence of acute infection and villous edema were associated with a higher pH and Poa and a lower Pcoa in both umbilical vein and artery. Umbilical vein or artery base excess was not related to placental lesions. Labor was not related to blood gas values in this data set, although a subset of cases of extremely preterm premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor who labored and were delivered by cesarean section had significantly poorer umbilical venous and fetal arterial blood gas values (all p < 0.005). Lesions related to poorer blood gas values were significantly more frequent in preterm preeclampsia and nonhypertensive abruptio placentae than in premature rupture of membranes or preterm labor. CONCLUSIONS: Changes in umbilical vein and artery pH, Poa, and Pcoa are significantly related to lesions of uteroplacental vascular pathologic mechanisms and intraplacental thrombosis. Placental lesions may be associated with chronic fetal distress by altering fetal oxygen availability and acid-base status. Placental immaturity resulting from prematurity may be associated with inefficient placental respiratory function and an increased likelihood of cesarean delivery in cases of premature rupture of membranes or preterm labor. Altered fetal acid-base balance plus excess numbers of circulating nucleated erythrocytes suggests that placental respiratory function is functionally abnormal when these lesions are present and leads to fetal tissue hypoxia. (AM J OBSTETGYNECOL1995; 173:1058-64.) Key words: Umbilical cord blood gases, prematurity, placental pathology, uteroplacental vessels From the Division of Anatomic Pathology, University of Connecticut Health Center,=the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School~St. Peter's Medical Center,'the Perinatal Pathology~ and Informatics d Sections, Perinatology Research Facility, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology" and Pathology/Georgetown University Medical Center, and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ponce School of Medicine. g Supported by National Institutes of Health contract No. NOI-HD 3-3198 (C.M.S., J.C.P., S.S.W.) and in part through an Interagency Personnel Agreement of the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) with the University of Connecticut (C.M.S.). Presented in part at the Fifteenth Annual Meeting of the Society of Perinatal Obstetricians, Atlanta, Georgia, January 23-28, 1995. Reprints not available from the authors. 6/6/67335 1058 Umbilical cord blood acid-base assessment is an objective method for the evaluation of the newborn, especially in cases of prematurity when Apgar scores may be unreliable. Placental histologic features have not been studied in relation to placental respiratory function. Traditionally, changes in pH values not accompanied by changes in base excess are considered indicators of respiratory acidemia. It is known that certain placental histopathologic lesions may be associated with decreased uteroplacental perfusion and fetal hypoxia. However, it is not known whether these lesions are "markers" for fetal hypoxia or whether their presence is directly related to abnormal placental hemodynamic function and abnormal placental respiratory exchange. Volume 173, Number 4 Am J Obstet Gynecol The current study examines placental histopathologic mechanisms in relation to umbilical venous and arterial cord blood gas values to test the hypothesis that uteroplacental vascular or placental structural pathologic features are directly related to abnormal placental respiratory function and potential fetal hypoxia and acidemia. Material and methods Beginning in April 1988 all placentas delivered at the J o h n Dempsey Hospital had pathologic examination. This data set represents all cases delivered between April 1988 and March 1994 that met the following inclusion criteria: singleton delivery, live birth, gestational age between 22 and 32 weeks by accurate gestational dating (by last menstrual period or early ultrasonography with confirmation by neonatal assessment), no maternal history of chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or placenta previa. The final data set was composed of 431 preterm placentas (22 to 32 weeks' gestation). The four primary indications for delivery were (1) premature rupture of membranes (n = 182) defined as rupture of membranes before onset of labor, (2) preterm labor (n = 150) defined as regular uterine contractions with cervical effacement and dilatation with intact membranes unresponsive to tocolysis, (3) preeclampsia (n = 72) defined as blood pressure > 140/90 mm Hg or increases of 30 m m Hg systolic or 15 m m Hg diastolic with proteinuria or edema and clinical symptoms or laboratory abnormalities warranting elective preterm delivery, and (4) nonhypertensive abruptio placentae (n = 27) defined as antepartum vaginal bleeding followed by preterm delivery. Clinical management at this institution results in essentially all cases of preeclampsia at < 32 weeks' gestation being delivered by cesarean section without a trial of labor. Subsets of this population have been previously studied.l-3 The current study derives from a master database of 462 patients who form the basis for a number of recent efforts examining the relationship of histologic features to various aspects of clinical outcome?' 5 Maternal charts were reviewed for principal indication for delivery, presence of labor, mode of delivery, and umbilical cord blood gas values. Blood samples for analysis were collected in heparinized 1 ml syringes, capped, and transported on ice to the laboratory for analysis. Blood gas values were determined within 10 minutes of delivery on a model 178 automatic pH analyzer (Corning Med, Boston). All placentas were studied by standard protocols. 6 For each case two samples of umbilical cord, two samples of extraplacental membranes, and four samples of grossly normal chorionic villi were examined. Additional tissue samples were taken from each gross lesion. If routine sampling of the basal plate did not contain uteroplacental arteries, several thin slices of the basal plate were Salafia et al. 1059 taken perpendicular to the maternal surface, embedded in a cassette, and processed. This technique increased the frequency with which uteroplacental vessels were identified and has been shown to identify a wide range of uterine vascular lesions. 7 Placental data recorded were placental weight and histopathologic lesions, which were classified into one of four groups: (1) histologic markers of acute ascending infection, (2) uteroplacental vascular lesions and villous lesions reflecting the effects of uteroplacental vascular pathologic mechanisms, (3) lesions of chronic inflammation, and (4) lesions related to coagulation. Each placental lesion was assigned to only one pathophysiologic group; therefore the four groups were mutually exclusive. Acute ascending infection. The presence and severity of acute maternal (in amnion, chorio decidua, chorionic plate) and fetal (e.g., umbilical cord and chorionic plate vessels) inflammation was scored on a scale of 0 to 4, as previously described. 8 Uteroplacental vascular pathologic features. The presence of uteroplacental vascular pathologic features can be inferred by lesions both in the uteroplacental vasculature and within the villous parenchyma. The two types of uteroplacental vascular lesions considered were fibrinoid necrosis and atherosis of uteroplacental vessels 9 and absence of physiologic change of uteroplacental arteries? ° Fibrinoid necrosis and atherosis were diagnosed when the uteroplacental vessel wall appeared smudged and eosinophilic, with or without mural foamy cells ("atherosis").l° Absence of a physiologic change of uteroplacental vessels was diagnosed when normal endovascular trophoblast destruction of the muscular and elastic components of the basal uteroplacental vessels did not occur or was incomplete. Incompletely converted vessels retain muscle and elastic in their walls and resemble spiral vessels of late luteal-phase endometrium? i, 12Villous lesions considered to be related to uteroplacental vascular pathologic features include abruptio placentae, ~3 villous infarcts, ~4 terminal villous fibrosis, increased syncytiotrophoblast knotting, cytotrophoblast (X-cell) proliferation, ~~ and villous hypovascularity. 16-1~The diagnosis of abruptio placentae was made by the gross finding of retroplacental hematoma with subjacent placental infarct or more commonly by microscopic evidence of placental villous infarct with decidual destruction and indentation with decidual and parabasal hemorrhage. Histologic diagnosis was considered to be consistent with (but not diagnostic of) abruptio placentae when focal regions showed decidual destruction and hemorrhage and an increase in syncytiotrophoblast knotting, often with villous stromal hemorrhage. Also, the presence of circulating nucleated erythrocytes was considered a potential marker for uteroplacental vascular pathologic mechanisms. Nucleated erythrocytes are not generally seen in smaller placental vessels after the early second trimes- 1060 Salafia et al. October 1995 Am J Obstet Gynecol Table I. Correlations of principal indications for delivery with umbilical cord blood gas values I Preeclampsia I Abruptioplacentae I UV pH UA pH UVPo~ UA Po2 UV Pco2 UA Pco2 UV base excess UA base excess 7.30 7.26 24 15.3 47 52 -2.7 -3.9 _+ 0.07 + 0.05 -+ 13.7 +- 7.8 __ 10.4 -+ 8.6 +_ 2.7 -+ 3.2 7.33 7.29 25.8 16.3 43.6 50 -2.3 -2.99 + 0.07 - 0.07 + 14 -+ 7.8 +- 10 + 12.5 -+ 2.7 -+ 3 PROM 7.37 7.31 33.7 21.7 38.1 45.7 -2.7 -3.3 _+ 0.07* - 0.08* _+ 9.8* + 6.4",t -+ 8* + 9,6" -+ 3,2 -+ 3.5 I PTL 7.37 7.31 32.2 22.4 38.3 43.3 -2.1 -3.5 +- 0.07* - 0.09* +- 11" -+ 7.7",t - 8* -- 11" -+ 3.6 +- 5.6 ]Significance p p p p p p < < < < < < 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 NS NS PROM, Premature rupture of membranes; PTL, preterm labor; UV, umbilical vein; UA, umbilical artery; NS, not significant. *Significant compared with preeclampsia. tSignificant compared with nonhypertensive abruptio placentae. ter. 19 A semiquantitative assessment described the presence of circulating nucleated erythrocytes as "occasional" if single cells were seen in rare fetal stem vessels or as "numerous" if several nucleated erythrocytes were seen in many fetal stem vessels and in smaller-caliber placental vessels. T h e presence of hemosiderin in decidua of basal plate or placental membranes was identified on light microscopy and confirmed by Prussian blue stain. L e s i o n s of chronic inflammation. Decidual plasma cell or eosinophil infiltrates, dense lymphocytic decidual infiltrates, chronic uteroplacental vasculitis,2° and villitis involving anchoring villi were diagnostic of chronic inflammation. Chronic, inflammation is reflected in the intervillous space and within placental villi by chronic intervillositis and chronic viUitis, respectively? 1, ~ Lesions r e l a t e d to coagulation. Coagulation-related lesions in the maternal circulation included uteroplacental vascular thrombosis and intervillous thrombosis. A diagnosis of excessive perivillous fibrin deposition indicated the presence of > 10% of villi encased in perivillous fibrin. Coagulation-related lesions within the placental circulation included chorionic and fetal stem vessel thrombi, "hemorrhagic endovasculitis, ~ and avascular terminal villi, indicating fetal microcirculatory vasoocclusion. Lesions such as uteroplacental vasculitis or absence of uteroplacental physiologic adaptation were considered as absent/solitary focus/multiple foci on a scale of 0 to 2. Semiquantitative assessments were applied to lesions such as villous fibrosis, hypovascularity, syncytiotrophoblast knotting, X-cell proliferation/~-~8 and perivillous fibrin deposition. Because these features differ quantitatively across gestation, the diagnostic pathologist (C.M.S.) was blinded to clinical data except gestational age. All lesions were scored with the pathologist blinded to the clinical data. Results were analyzed by contingency tables and analysis of variance, with p < 0.05 considered significant after Scheffe's corrections for multiple comparisons. Results T h e umbilical blood gas characteristics of the population are presented in Table I. T h e mean gestational age in cases of premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor were significantly shorter than in cases of preeclampsia (p < 0.05), with cases of nonhypertensive abruptio placentae showing a borderline trend to shorter gestational age c o m p a r e d with cases of preeclampsia (p = 0.058, Scheffe's test). Venous values were available in 431 patients and arterial values in 405 patients. Decreased umbilical vein and artery p H and Po 2 and increased Pco2 were observed in cases of preeclampsia c o m p a r e d with cases of premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor (p < 0.05), and decreased umbilical artery Po 2 was seen in nonhypertensive abruptio placentae c o m p a r e d with cases of premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor (p < 0.05). Table II lists the significant relationships of placental lesions to umbilical vein and artery pH, Po2, and Pco 2. Uteroplacental vessels were available for review in 414 of 431 (96%) of cases. Placental lesions related to uteroplacental vascular pathologic features, chronic villitis, and coagulation-related lesions demonstrated general associations with decreased umbilical vein and artery pH, and Po2 and increased Pco~, whereas the presence of acute infection and villous e d e m a were generally related to increased umbilical vein and artery p H and Po2 and decreased Pco2. Placental lesions related to uteroplacental vascular pathologic features, chronic viUitis, and coagulation-related lesions were significantly less likely to occur in placentas in which acute amnionitis, choriodeciduitis, chorionitis, chorionic vasculitis, umbilical vasculitis, and moderate or severe villous e d e m a were identified (eachp < 0.05). Acute amnionitis, choriodeciduitis, chorionitis, chorionic vasculitis, umbilical vasculitis, and moderate or severe villous e d e m a were significantly more common in premature rupture of membranes or p r e t e r m labor than in preeclampsia or nonhypertensive abruptio placentae (each p < 0.05). Stepwise regression isolated four variables that demonstrated significant indepen- Volume 173, Number 4 Am J Obstet Gynecol dent predictive values to umbilical cord blood gas values (histologic evidence of abruptio placentae, villous infarct, villous hypovascularity, and avascular villi, R 2 = 0.10). For example, when umbilical vein p H was considered, coefficients for these lesion variables indicated that for each change in lesion severity (see Table II) a change in pH of approximately 0.10 would be predicted. Because labor was generally not permitted in cases of preterm preeclampsia, labor was therefore separately analyzed in the premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor groups. Seventy-five cases in the premature rupture of membranes-preterm labor group did not labor and showed a mean umbilical vein pH of 7.37 -+ 0.06 compared with 247 cases that labored and demonstrated an umbilical vein pH of 7.37 + 0.08 (not significant). Of the 247 cases of premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor that labored, 109 were eventually delivered by cesarean section. The mean umbilical vein p H of this group was 7.35 -+ 0.07 compared with 7.39 -+ 0.08 for the cases delivered vaginally (p < 0.003). These 109 patients also had significantly decreased umbilical artery p H (7.28 -+ 0.07 vs 7.32 0.08, p = 0.003) and a mean elevation of 7 m m Hg in umbilical vein Pco 2 (p < 0.0001), 5 mm Hg in umbilical artery Pcoz (p < 0.0005), and a mean decrease of 3 mm Hg in umbilical artery P o 2 (p < 0 . 0 0 2 ) compared with those patients who labored and delivered vaginally. The 109 patients who labored but were subsequently delivered by cesarean section were also significantly younger than those who labored and delivered vaginally (191 -+ 16 days vs 199 -+ 18 days, p < 0.006). These 109 patients did not have significantly different incidences or severity of uteroplacental vascular lesions, villous lesions reflective of the effects of impaired uteroplacental perfusion, or obliterative lesions within the placental vasculature itself (data not shown, each p > 0.05). Comment Quantitative changes in umbilical venous and fetal arterial pH, Pco2, and Po 2 are related to two categories of uteroplacental and placental histologic lesions: (1) uteroplacental vascular lesions (which restrict uteroplacental perfusion) and villous lesions believed to reflect the effects of impaired uteroplacental perfusion and (2) obliterative lesions within the placental vasculature itself. Lung function can be impaired by structural processes (e.g., reduced lung volume, increased thickness of the tissue diffusion barrier, decreased alveolar capillary bed) or by physiologic processes (poor quality of inspired air or decreased capillary flow rates). Lesions affecting anatomic equivalents of each of these sites can be observed in the placenta. An intact uteroplacental circulation ensures adequate intervillous perfusion and oxygen delivery to the conceptus; uteroplacental blood Salafia et al. 1061 flow progressively increases in the last trimester of pregnancy. The diffusion distance across the trophoblast is greater in preterm placentas than at term; vasculosyncytial membranes that reduce the diffusion distance across the placenta do not develop until the late second trimester. Our data suggest that there is a difference in placental functional reserve or capacity to withstand the stresses of labor that is best measured by the gestational age of the placenta and not marked by any histologic lesions. Our cases of premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor that labored but required cesarean delivery demonstrated poorer umbilical venous and fetal arterial blood gas values, younger gestational age at delivery, and no difference in incidence of placental parenchymal lesions compared with cases that labored and delivered vaginally at a significantly greater gestational age. The more preterm the placenta, the greater may be its relative functional inefficiency-independent of pathologic lesions. However, pathologic disorders may further alter the intrinsic respiratory capacity of the placenta at any given gestational age. Increased amounts of perivillous fibrin deposition would impair gas diffusion. Cytotrophoblast (X-cell) proliferation would increase the thickness of the trophoblast layer. Areas of syncytiotrophoblast knotting demonstrate "aging ''~8 or degenerative nuclear changes and may be functionally abnormal. Internal to the respiratory exchange surface, villous fibrosis, hypovascularity, or frank obliteration of areas of the villous capillary bed (in avascular villi or infarcts) would reduce the capillary area for exchange, and may have an impact on placental resistance and ultimately placental blood flow through the villous capillary bed. Areas of abruptio placentae would combine effects at several levels (impairment of maternal perfusion, damage to the trophoblast surface, and initial compression and eventual obliteration of the placental capillary bed). It is important to note that the absence of physiologic changes or fibrinoid necrosis or atherosis of the uteroplacental vascular lesions themselves was not correlated with umbilical blood gas values. Rather, blood gas values were related to placental lesions, which are believed to reflect their effects. Other analyses of this data set have suggested that it is not so much uteroplacental vascular lesions but the placental response to the pathologic anatomy and physiologic features that is critical to fetal outcome. 23 These data further support that hypothesis. In our data set the actual values of umbilical vein and artery pH, Po2, and P c o 2 a r e within the normal limits in most cases. We even found no association of labor with blood gas values in premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor patients, the only groups that labored in this population. This may reflect the clinical management at the John Dempsey Hospital, where 1062 Salafla et al. October 1995 Am J Obstet Gynecol Table II. Significant r e l a t i o n s h i p s o f p l a c e n t a l lesions to umbilical b l o o d gas values UV pH Acute inflammation Amnionitis (maternal response) Grade 0 Grades 1-2 Grades 3-4 Umbilical vasculitis (fetal response) Grade 0 Grades 1-2 Grades 3-4 Uteroplacental vascular pathologic features Fibrinoid necrosis/atherosis None One vessel Multiple vessels Placental lesions related to uteroplacental vascular pathologic features Histologic features related to abruptio placentae None Consistent with abruptio placentae Gross abruptio placentae Villous infarct None Single Multiple Syncytiotrophoblast knotting Normal Moderate increase Severe increase Cytotrophoblast ("X-cell") proliferation Normal Moderate increase Severe increase Villous fibrous Normal Moderate increase Severe increase Villous hypovascularity Normal Moderate increase Severe increase Circulating nucleated erythrocytes Normal Moderate increase Severe increase Chronic inflammation Chronic villitis Not present Present Coagulation-related lesions Uteroplacental vessel thrombus No occlusive One occlusive Multiple occlusive Perivillous fibrin deposition Normal for age Moderate increase for age Avascular terminal villi None Focal Multifocal Miscellaneous (unclassified) lesions Villous edema None Mild/moderate Severe UA pH 7.35 ± 0.08* 7.38 -+ 0.06* 7.37 _+ 0.60* UV Po2 (mm Hg) 29.7 - 13.3" 33.5 -+ 11.4" 34.8 ± 8.8* 7.35 ± 0.07* 7.38 - 0.06* 7.38 -+ 0.07* 31.57 -+ 12.355 29.09 -+ 8.745 20.03 ± 5.095 7.37 + 0.07t 7.35 ± 0.07t 7.34 _ 0.08t 7.32 ± 0.0St 7.30 ± 0.08t 7.28 - 0.09? 7.37 _+ 0.07t 7.33 - 0.07t 7.31 ± 0.08t 7.31 ± 0.0St 7.27 ± 0.08t 7.26 - 0.06t 32.55 + 11.17t 27.90 -+ 17.72t 23.92 - 12.70t 7.37 -+ 0.07t 7.35 ± 0.0St 7.32 + 0.06 7.31 _+ 0.08t 7.29 - 0.08t 7.27 ± 0.07t 33.5 - 11.4t 30.2 -+ 12.7t 24.9 ± 13.3t 7.36 -+ 0.07t 7.35 - 0.07t 7.32 +- 0.08t 32.3 ± 10.4t 31.4 + 17.2t 24.5 ± 10t 7.36 - 0.08* 7.35 _ 0.07* 7.32 ± 0.06* 7.36 -+ 0.07t 7.34 - 0.07t 7.30 + 0.09t 7.30 _+ 0.08* 7.30 ± 0.06* 7.25 ± 0.10" 32.0 -+ 11.0" 30.8 - 15.5' 24.3 -+ 12.9" 7.31 ± 0.07t 7.29 - 0.09t 7.26 +- 0.0St 32.2 ± 10.0" 31.4 +-_ 14.8" 23.3 - 8.2* 7.36 ± 0.07* 7.32 -+ 0.06* 7.30 -+ 0.085 7.27 +_ 0.065 7.36 ± 0.07t 7.33 -+ 0.08t 7.33 ± 0.0St 7.31 - 0.08* 7.28 -+ 0.10" 7.28 ± 0.06* 7.34 -+ 0.07* 7.37 ± 0.07* 7.35 ± 0.09* 7.28 -+ 0.08* 7.31 _+ 0.07* 7.30 ± 0.12" All empty cells indicate nonsignificant results. UV, Umbilical vein; UA, umbilical artery. *p < 0.01. tp < 0.001. Sp < 0.05. Salafia et al. Volume 173, Number 4 Am J Obstet Gynecol UA Poa (ram Hg) 19.7 -+ 7.7* 21.4 +- 6.6* 23.0 ± 7.3* UV Pco2 (mm Hg) 1063 UA Pco2 (ram Hg) 41.6 + 9.5t 37.3 -+ 6.7t 37.4 _+ 6.6t 47.1 ± 10.7" 46.2 -+ 8.5* 42.7 + 11.2" 38.32 ± 8.38t 40.00 -+ 7.89t 42.64 ± 9.86t 43.78 -+ 9.76t 46.72 +- 10.03t 49.04 -+ 11.55t 21.5 -+ 7.1t 18.3 -+ 9.5t 14.7 +- 6.5t 38.58 + 8.02t 45.47 ± 10.29t 46.2 -+ 9.17t 44.69 -+ 10.29# 52.55 -+ 10.14t 52.10 -+ 9.11t 21.8 -+ 7.3t 20.37 ± 7.5t 15.9 ± 7.7t 38.20 -+ 8.14t 40.89 ± 9.25t 45.36 -+ 8.10t 44.80 -+ 0.19" 46.92 -+ 11.26" 50.06 -+ 8.60* 21.5 ± 6.8t 20.6 ± 8.9t 15.3 ± 7.7t 38.87 -+ 8.36t 40.80 ± 9.15~ 45.45 -+ 9.16t 45.28 -+ 0.15" 46.51 -+ 10.40" 51.00 -+ 12.40" 21.4 -+ 7.0t 20.4 -+ 8.4t 15.8 -+ 5.7t 38.74 ± 8.45t 41.00 ± 9.23t 45.08 -+ 7.99t 44.95 -+ 10.78" 46.93 ± 10.48" 51.52 + 7.59* 21.5 -+ 7.4t 19.5 -+ 7.5t 14.l ± 6.3t 38.89 -+ 8.36t 41.39 _+ 9.007 47.58 ± 9.55t 44.95 ± 10.26t 47.24 + 10.01t 55.79 ± l l . 1 5 t 21.5 -+ 7.0* 20.3 - 7.9* 15.5 +- 8.0* 39.16 + 7.91++ 40.45 -+ 9.51++ 43.51 -+ 10.105 45.39 -+ 10.025 46.38 -+ 10.855 50.80 ± 2.18++ 21.0 - 7.4t 13.6 -+ 6.6t 39.73 -+ 8.86* 44.29 + 7.90* 45.88 -+ 10.51++ 50.79 -+ 10.93++ 21.3 -+ 7.85 20.6 ± 6.15 19.0 -+ 6.75 39.1 ± 8.25 39.9 -+ 6.9++ 41.8 + 0.45 19.8 ± 7.7* 21.6 -+ 6.6* 22.8 -+ 7.0* 20.8 + 7.5++ 21.6 + 6.75 13.6 -+ 4.7++ 20.79 -+ 7.50 + 21.63 - 6.705 21.42 + 7.10t 18.22 +- 8 .75t 16.68 -+ 7 . 11t 39.08 - 8.73t 42.82 -+ 9.64t 43.39 -+- 5.71t 45.21 -+ 10.13" 48.93 -+ 12.60" 50.34 -+ 8.36* 19.25 -+ 7.62++ 21.15 ± 7.20++ 21.93 -+ 8.805 42.81 -+ 8.917 38.43 -+ 8.38t 39.72 -+ 9.25t 49.51 -+ 10.18t 44.46 -+ 10.13t 44.72 + 12.18t 1064 Salafia et al. each p r e t e r m presentation is extensively evaluated by biophysical profile scores and r e p e a t e d tests of fetal well-being. Any fetus that demonstrates a potential for "decreased placental reserve" by showing an abnormality in antepartum testing is promptly delivered by cesarean section. In cases of p r e m a t u r e rupture of membranes and preterm labor that are allowed to labor, clinical triage has selected those cases with placentas better able to maintain umbilical venous (and by extension fetal artery blood gas values) at healthy levels. However, in our data placental lesions may contribute to as much as 10% of the variation in blood gas values. Why not a greater percent? First, this study does not consider potential physiologic modifiers of placental respiratory function. None of our patients were diagnosed with sickle cell disease or other frank hemoglobinopathy; major differences in the oxygen-carrying capacity of maternal blood delivered to the intervillous space is not likely. Retrospective data regarding maternal smoking are frequently unreliable. We also did not have available data regarding fetal cardiac status or studies of Doppler velocimetry. However, the same lesions are associated with the release of nucleated erythrocytes (a process that is most commonly attributed to hypoxia) and to symmetric and asymmetric intrauterine growth retardation. 23 T h e maintenance of fetal acid-base balance on the lower end of the normal range in the face of chronic placental parenchymal d a m a g e may due to chronic fetal accommodations to impaired placental function. We speculate that placental lesions play a causal role of impairing placental respiratory function and umbilical vein blood quality, leading to chronic fetal hypoxia and restricted fetal metabolism and growth. These fetal compensations restore acid-base balance within the homeostatic range but may not be without cost to the fetus. In any p r e t e r m population statistical relationships of blood gas values to labor will d e p e n d on the clinical mix of preeclampsia and spontaneous prematurity and on the clinical m a n a g e m e n t of laboring patients. Maternal maneuvers to increase uterine perfusion and maternal oxygen content may have different effects of fetal oxygenation and acid-base status d e p e n d i n g on the anatomic site of impairment of the uteroplacental respiratory apparatus. Prospective studies of the fetal response to such interventions, which include detailed placental histopathologic study, may improve our ability to diagnose the nature of uteroplacental respiratory impairm e n t and indicate the most efficient target therapy. REFERENCES 1. Wolfe E, Vintzileos AM, Salafia CM, Rosenkrantz T, Rodis JF, Pezzullo JC. Do survival and morbidity of the very low birth weight infant vary according to primary pregnancy complications resulting in preterm delivery? AMJ OBSa'ET GVNECOL1993;169:1233-9. 2. Salafia CM, Ernst L, Pezzullo JP, Wolf w, Rosenkrantz TS, October 1995 Am J Obstet Gynecol Vintzileos AM. Thevery low birth weight infant: maternal complications leading to preterm birth, placental lesions, and intrauterine growth. Am J Perinatol 1995;12:106-10. 3. Salafia CM, Minior VK, Rosenkrantz TS, Pezzullo JC, Cusick W, Vintzileos AM. Maternal, placental and neonatal associations with early germinal matrix/intraventricular hemorrhage in infants born at < 32 weeks gestation. Am J Perinatol 1995 [In press]. 4. Salafia CM, L6pez-Zeno JA, Sherer DM, Whittington SS, Minior VK, Vintzileos AM. Histologic evidence of old intrauterine bleeding is more frequent in prematurity. AM J OBSTrTGVNECOL1995;173:1065-70. 5. Salafia CM, Minior VK, Pezzullo JC, Popek EJ, Rosenkrantz TS, Vintzileos AM. Intrauterine growth restriction in infants of less than thirty-two weeks' gestation: associated placental pathologic features. AM J OBsxEx GYNECOL 1995;173:1049-57. 6. Salafia CM. Placental pathology in perinatal diagnosis. In: Sciarra J, ed. Gynecology and obstetrics (revised). Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1993:1-39. 7. Khong TY, Chambers HM. Alternative method of sampiing placentas for the assessment of uteroplacental vasculature. J Clin Pathol 1992;45:925-7. 8. Salafia CM, Weigl C, Silberman L. The prevalence and distribution of acute placental inflammation in uncomplicated term pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 1989;73:383-9. 9. Khong TY, Pearce JM, Robertson WB. Acute atherosis in preeclampsia: maternal determinants and fetal outcome in the presence of the lesion. AMJ OaSTETGVN~COL1987;157: 360-3. 10. Brosens I, Dixon FIG, Robertson WB. Fetal growth retardation and the arteries of the placental bed. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1977;84:656-63. 11. Robertson WB, Khong TY, Brosens I, et al. The placental bed biopsy: review from three European centers. AM J OBsxEx GVNECOL1986;155:40!-12. 12. Dommisse J, Tiltman AJ. Placental bed biopsies in placental abruption. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;99:651-4. 13. Brosens "I, Renaer M. On the pathogenesis of placental infarcts in preeclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1972;79:794-9. 14. Fox H. Effect of hypoxia on trophoblast in organ culture. AMJ OBSTETGYNECOL1970;107:1057-64. 15. Lowell DM, Kaplan C, Salafia CM. College of American Pathologists conference XIX on the examination of the placenta: report of the working group on the definition of structural changes associated with abnormal function in the maternal/fetal/placental unit in the second and third trimester. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991;115:647-731. 16. Perrin EVDK. In: Bennington JL, ed. Pathology of the placenta. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1978. 17. Fox H. In: Bennington JL, ed. Pathology of the placenta. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1978. 18. Salafia CM, Weigl CA, Foye GJ. Correlation of placental erythrocyte morphology and gestational age. Pediatr Pathol 1988;8:495-503. 19. Erlendsson K, Steinsson K, J6hannsson JH, Geirsson RT. Relation of antiphospholipid antibody and placental bed inflammatory vascular changes to the outcome of pregnancy in successive pregnancies of 2 women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 1993;20:1779-85. 20. Redline RW, Abramowsky CR. Clinical and pathological aspects of recurrent placental villitis. Hum Pathol 1985; 16:727-31. 21. Altshuler G, Russell P. The human placental villitides: a review of chronic intrauterine infection. Curr Top Pathol 1975;60:64-112. 22. Stevens NG, Sander CH. Placental hemorrhagic endovasculitis: risk factors and impact on pregnancy outcome. IntJ Gynecol Obstet 1984;22:393-7. 23. Salafia CM, Pezzullo CM, L6pez-Zeno JA, Simmens S, Minior VK, Vintzileos AM. Placental pathologic features of preterm preeclampsia. AM J OBSTET GYNECOL1995;173: 1097-105.