HEALTH AND WELL-BEING OF NUI GALWAY UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS: THE STUDENT LIFESTYLE SURVEY

advertisement

HEALTH AND WELL-BEING OF NUI GALWAY

UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS:

THE STUDENT LIFESTYLE SURVEY

PÁDRAIG MACNEELA1, CINDY DRING2, ERIC VAN LENTE,

CHRISTOPHER PLACE, JOHN DRING AND JOHN MCCAFFREY1

1

SCHOOL OF PSYCHOLOGY

2

STUDENT SERVICES

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND, GALWAY

1

2

1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the support and assistance of NUI Galway students

and staff in carrying out this study. Matt Doran, Mary O'Riordan and Una

McDermott merit special mention of our appreciation. We would also like to

acknowledge the assistance and facilities provided by Student Services,

Management Information Systems and the School of Psychology. The NUI

Galway Student Projects Fund supported the study through a project grant.

The research was conducted independently and as the lead authors we take

responsibility for the opinions expressed in the report. Our co-authors assisted

us in designing the survey and data collection (Christopher Place), analysis of

the data set and drafting the findings (Eric Van Lente, John Dring, John

McCaffrey).

We hope the Student Lifestyle Survey report will provide useful information

on the experience of undergraduate students at NUI Galway. The health and

well-being of students are important concerns of the University community.

The information we provide could help further target the extensive skills,

resources and research expertise available on campus. In addition to

identifying priorities for supporting health, the survey findings are a baseline

for comparison in the future.

Dr Pádraig MacNeela, Lecturer, School of Psychology, and Cindy Dring, MA,

Health Promotion Officer, Student Services.

June 2012

2

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. INTRODUCTION

Student physical, mental, and social well-being is centrally important to the

university experience. The 2009-2014 Strategic Plan for the National

University of Ireland, Galway (NUI Galway) is committed to preparing

graduates for learning, life and work, in part through a holistic educational

experience and support services. The university environment ought to enable

personal and social development alongside the educational experience. The

Irish Universities Quality Board (IUQB) described student support services as

contributing to this process, "by providing professional services which support

the holistic development of the person, thereby enabling all students to

achieve their full academic and personal potential" (IUQB, 2006, p. 9).

Student welfare services are designed to support and encourage students to

make choices conducive to positive health and well-being. Lifestyle choices

can have a profound impact on students at university and subsequently.

Evidence is therefore required to identify priority issues for student support

services and the university community more generally. The Student Lifestyle

Survey was carried out to assess student health and well-being and as a

baseline to measure change over time. The findings can be used to inform

policies and strategies aimed at supporting students.

2.2. STUDENT WELL-BEING

The transition to third level is a critical period. In the course of attending

university, students form friendships, new living arrangements and social

patterns. This experience is one of the most positive and memorable stages in

life. However, going to college is also a time when adjustment difficulties and

harmful health-related behaviours can become established. Thus, university

life brings challenges such as managing lifestyle choices, the development of

self care skills and personal independence (Parker et al., 2002). Students

encounter and must adjust to new demands in social, academic and financial

domains. It is, therefore, important to engage with students in relation to

their health in order to support successful university experience, linked to

both academic performance and student retention (DeBerard et al., 2004;

Pascarella et al., 2007).

2.3. THE STUDENT LIFESTYLE SURVEY

The Student Lifestyle Survey (SLS) was carried out to explore the behaviours,

perceptions and experiences of a cross-section of NUI Galway undergraduate

students. The College Lifestyle and Attitudes National (CLAN) Survey was

used as a guide in planning the study (Hope et al., 2005). The CLAN survey

was carried out in 2002 with a sample of 3,259 full-time undergraduate

students. It established a profile of student lifestyle habits in respect of

general and mental health, diet, exercise, accidents and injuries, sexual

3

health, substance use and drinking patterns. This was the first survey of

health behaviours and attitudes among third level students in all Irish

universities and Institutes of Technology. Coping skills, work / study balance,

and alcohol-related harm were particular areas of concern identified in the

findings. The CLAN survey found that regular binge drinking was associated

with a cluster of risky or harmful behaviours, such as cannabis use and

cigarette smoking and other negative consequences such as money problems,

academic difficulties, fights and unprotected sex (Hope et al., 2005). The

definition of binge drinking used in the SLS is the same as that used in the

CLAN survey, namely, consuming eight or more standard drinks on one

drinking occasion. This equates to four pints of beer, a bottle of wine or seven

single measures of spirits (Hope et al., 2005).

Drawing on the CLAN survey, the SLS was designed to provide an updated

picture of health behaviours and attitudes among NUI Galway students. It

also extended the CLAN survey methodology, by including a wider range of

mental health questions and a section on student engagement.

2.4. RESEARCH AIM

The Student Lifestyle Survey was designed as a cross-sectional survey of NUI

Galway students on attitudes, health behaviours and academic engagement,

to address the following aims:

Provide an overview of lifestyle habits and attitudes among

undergraduate students.

Make a comparative analysis of responses to different survey topics

according to gender and year of study.

Provide baseline data on health behaviours, such as drinking patterns,

drug use, and smoking to inform initiatives that support student health

and well being.

2.5. SUPPORT AND FUNDING

Funding to carry out the Student Lifestyle Survey was provided by the

Student Project Fund at NUI Galway, following approval of the project

proposal. A consultation group was formed to guide survey development,

comprising university staff from the Centre for Excellence in Learning and

Teaching, college advisory services, Student Services, the Students Union,

Counselling Services, and the Health Promotion Research Centre. The study

received approval from the University‟s Research Ethics Committee.

4

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. DESIGN

Students responded to a self-administered survey that was hosted on an

online survey website. The sampling frame comprised all full-time

undergraduate students. Students were randomly sampled from a list

provided through university databases, using a stratified sampling procedure

to elicit proportional representation from NUI Galway colleges and by year of

course. Students were contacted to take part by sending an invitation to their

university email address. A prize draw was provided as an incentive to

complete the questionnaire.

A response rate of approximately 30% was anticipated. Given the intention to

conduct statistical analysis of sub-groups, a target sample size of 1,202 was

calculated. Therefore an invitation was sent to 3,500 students using a

sampling frame provided through university information services. The delivery

of 37 emails failed, and 986 students responded, giving a response rate of

28%. Analysis of responses by item indicated non-completion of some survey

items, especially toward the end of the survey. A final sample of 841 students

was retained following appraisal of missing data, and is the sample used in

presenting the findings.

3.2. SUMMARY OF STUDENT LIFESTYLE SURVEY CONTENT

The survey form was divided into seven topics (Appendix 1). Validated

measures were included along with items from international, national and

college surveys. We drew on the CLAN survey questionnaire for items and

reviewed surveys such as SLÁN, HBSC, ESPAD, the Trinity College study on

sexual health, the Higher Education Authority European Student Survey and

the international ECAS study on drinking patterns.

The SLS comprised the following sections:

1. Welcome. Introduction to the purpose of the research, study

information and contact details for the researchers.

2. About you. Demographic items adapted from the CLAN survey.

3. General health, food habits and tobacco use. One-item measure

of physical health (CLAN); tobacco use indicators from the 2007 SLAN

survey (Morgan et al., 2008); items on fruit and vegetable intake

based on current HSE healthy eating guidelines; items on sleep

adapted from the Sleep Heart Health Study Questionnaire (Quan et al.,

1997).

4. Alcohol use. CLAN items on drinking frequency, consumption of

specific drinks, frequency of binge drinking (four pints of peer, a bottle

of wine, seven single measure of spirits, six premixed spirits), harmful

5

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

consequences of drinking; the RAPS 4 four-item measure of clinically

significant alcohol dependence during the last year (Cherpitel, 2000).

Other substances. Items on frequency and recency of cannabis use

(CLAN); the Severity of Dependence Scale to assess cannabis

dependence (Martin et al., 2006); items to assess frequency of use of

other drugs (CLAN).

Sexual health. Items on sexual activity status, condom use,

emergency contraception, based on the American National Longitudinal

Study of Adolescent Health (Udry, 2003), the Youth Risk Behavior

Surveillance System (CDC, 2009) and CLAN.

Mental health. One item mental health measure (CLAN); perceptions

of stress measure adapted from CLAN scale (response options from

'very often' to 'never'); the physical vitality and mental health subscales of the SF-36 measure of health and well-being (Ware, 1993).

Student engagement. The first section of the Shortened Experiences

of Teaching and Learning Questionnaire for higher education (items 18; ETL Project, 2005); Supportive Campus items from the US National

Survey of Student Engagement Benchmarks of Effective Educational

Practice (Kuh, 2001); the Basic Needs Satisfaction measure of selfdetermination (measures of perceived autonomy, competence, and

social relatedness; Gagne 2003); evaluation of the educational

experience at NUI; overall mark for the previous academic year (or

Semester 1 mark for first years); awareness of student support

services and university facilities; hours per week spent in volunteering,

sports participation, societies and club.

Thank you. Information on student support services.

3.3. PROCEDURE

The survey content was developed in consultation with the project steering

committee. We recruited university staff and student representatives to this

group to draw on specialised knowledge of the student experience. This

collaborative approach assisted in item design and selection of standardised

measures. The SLS was presented online. We designed a survey form hosted

on a survey website, and piloted it with 20 students. The final form was

completed following feedback on layout, question formulation and overall

design. Completion of the survey required approximately 35 minutes. The

steering committee approved the final version of the survey. Data collection

took place during in spring 2009, avoiding exam periods and holidays.

An invitation email with introductory information on the survey was sent to

randomly selected undergraduate students. A link to the survey webpage was

provided in the email. A reminder was sent after 10 days and again three

weeks following the initial mass email. We were permitted to make

announcements before class and used posters and flyers to raise awareness

of the survey on the campus.

6

On clicking the email link, the respondent was taken to the survey welcome

page, giving information on the SLS and contact information for the

researchers. Students were informed that by clicking to go to the next page

the survey would begin, and that they could discontinue at any time. The

participants were given the option to email a named researcher to enter the

draw. This method ensured we did not link the person to individual survey

responses. The data were downloaded and organised into a data set using

the SPSS 18 package for statistical analysis. Descriptive information was

reviewed during data cleaning and decisions made about missing entries in

the survey, resulting in a final sample of 841 participants. A targeted

statistical analysis of the data followed an initial analysis of trends, using

descriptive methods and inferential statistical tests. We used the chi-square

test, parametric correlations, t-test for independent samples and linear

regression inferential tests.

7

4. RESULTS

4.1. DEMOGRAPHICS

The NUI Galway Student Lifestyle Survey returned a sample of 841 full-time

undergraduate students. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of

the sample, across year of study, College, and accommodation type. The

students were mostly female and predominantly aged under 21 (females:

59%, males: 41%).

Table 1: Presentation of survey respondent demographics expressed in

percentages, by gender

No of respondents

Gender

Age category

% aged under 21 years

21-24 years

25 +

Year in college

1st year

2nd year

rd

3 year plus

College of study

Arts, Social Sciences and Celtic Studies

Business, Public Policy and Law

Engineering and Informatics

Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences

Science

Relationship status

Married

In a relationship

Single

Accommodation type

Lodgings

Parents / guardians

College residence

Rented house

Living with partner and/or children

Nationality

Irish national

Non-Irish national

Males

N=341

%

40.5

Females

N=500

%

59.5

Total

N=841

%

80.1

11.1

8.8

79.0

13.4

7.6

79.4

12.5

8.1

32.4

38.7

28.9

34.5

38.9

26.6

33.7

38.8

27.5

22.8

19.3

25.5

6.5

25.8

38.9

17.2

4.3

18.6

21.1

32.4

18.1

12.9

13.6

23.0

2.6

34.6

62.8

1.4

42.9

55.7

1.9

39.5

58.6

3.5

24.4

17.1

52.1

2.9

3.6

18.9

22.1

52.0

3.4

3.6

21.2

20.0

52.0

3.2

95.0

5.0

93.9

6.1

94.4

5.6

4.2. LIVING CONDITIONS – INCOME, EXPENDITURE, TIME

ALLOCATION

This section explores the demographic characteristics of the students in more

detail, focusing on finances and how students reported using their time.

8

4.2.1. Income

Family was the predominant source of income, with 75% of the students

receiving this support, followed by paid employment (42%). Over one quarter

(28%) received a local authority or State grant. Much smaller percentages of

students (6-7%) reported income from a fellowship or scholarship, social

welfare payments or bank loans. There were variations in the amount

typically received in each income category. Although a small proportion

received social welfare, the average amount of €620 per person in receipt of this

income was larger than the amount typically received from the family (€382) or

employment (€354). A broadly consistent pattern was reported across year of

study, although the proportion of students working reached a peak in Year 2.

Male students in employment reported receiving higher income from this

source than their female counterparts (€382 compared with €336).

Table 2: Sources of monthly incomea and mean income from each source in

Euro, by gender

Students with

this income

source (N, %)

630 (75%)

357 (42%)

238 (28%)

Malesb

Femalesb

Family

€374

€386

Employment

382

336

Local Authority/State

Grants

330

343

Fellowships/Scholarships

55 (7%)

457

299

Social Welfare

51 (6%)

659

589

Bank Loans

50 (6%)

256

298

a only for students with this source of income

b 5% trimmed mean for just those who have this source of income

Totalb

€382

354

338

359

620

282

4.2.2. Expenditure

Those students not living at home reported accommodation as their largest

single expense. Seventy-two per cent reported expenditure on

accommodation, with males and females reporting paying similar amounts

(€343). Some expenditure categories were nearly ubiquitous. Nearly all

reported expenditure on food (97%) and phone (92%). Among those who

reported a particular expenditure category, an average of €135 was spent on

food, compared with €89 for alcohol, €62 for transport, €62 for tobacco, and €51 on

regular bills such as electricity.

9

Table 3: Mean monthly expenditurea in Euros, by gender

Students with

Malesb

this expense

(N, %)

Food

812 (97%)

€147

Phone

777 (92%)

25

Clothing and toiletries

702 (83%)

31

Alcohol

679 (81%)

112

Transport

676 (80%)

58

Entertainment

649 (77%)

46

Accommodation

601 (72%)

342

Study materials

551 (66%)

23

Regular bills (ESB, etc.)

516 (61%)

50

Medical expenses

223 (27%)

25

Tobacco

139 (17%)

60

Grinds

29 (3%)

34

a only for students with this source of expense

b 5% trimmed mean for just those who have this expense

Femalesb

€128

26

46

76

64

41

344

27

51

18

63

55

Totalb

€135

26

41

89

62

43

343

25

51

20

62

46

4.2.3. Time allocation and academic performance

The students reported an average of 17.3 hours spent in the classroom

during a typical week during the semester (Table 4). This compared with an

average of 10.6 hours reported for personal study (i.e., academic activities

outside class). Those with part-time jobs reported working 12.7 hours per

week on average.

Table 4: Mean number of hours allocated per week to academic and paid

work, by gender

Male

17.5

9.7

12.7

Classes/tutorials

Personal study (not exam time)

Paid employment (among those working)

Female Total

17.1

17.3

11.1

10.6

12.6

12.7

Table 5 reports on extracurricular activities. Taking part in sports was the

most prevalent type reported. Nearly half of the sample reported this activity.

When time spent playing sports was averaged, men allocated significantly

more time playing sports than women did. One in eight (13.3%) students

reported volunteering, compared with 24.4% who considered themselves

active in society activities and a similar proportion (25.4%) involved in sports

clubs. Taken together, 43.8% were active in one or more form of organised

extracurricular involvement (i.e., sports clubs, societies, volunteering). Spread

across the entire group, the mean number of hours spent playing sports was

2.5 hours per week, compared with 1.1 hours for sports clubs, 0.9 hours for

societies, and 0.4 hours for volunteering.

10

Table 5: Mean number of hours allocated per week to extracurricular

activities, by gender

Male

Female

Sports

3.7

Sports clubs

1.5

University societies

0.9

Volunteering

0.4

*Significant between gender (p<.05)

**Significant between gender (p<.01)

1.7

0.7

0.8

0.4

Total

2.5**

1.1**

0.9

0.4

% Reporting

this activity

46.4

24.4

25.4

13.3

Of the total sample, 767 students reported on academic performance in the

past year ("thinking about your previous year, what was your average %

mark? For first years, what was your semester one mark?"). Table 6 displays

percentages of students in different grade categories, organised by gender.

Females reported a slightly higher mark on average, but this difference was

not statistically different.

Table 6: Percentage of students in each category of academic marks, by

gender

49% or less

50-59%

60-64%

65-69%

70-80%

80%+

Males

17.2

28.6

19.8

18.5

12.3

3.6

Females

14.6

26.4

23.8

16.6

16.6

2.2

Total

15.7

27.3

22.2

17.3

14.8

2.7

4.3. GENERAL HEALTH, MENTAL HEALTH, STRESS AND WELL-BEING

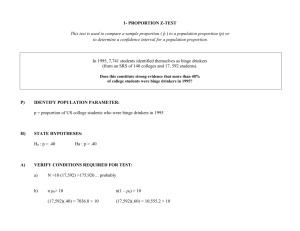

4.3.1. General Health

Students were invited to rate their general health using a one-item measure

with five options, from 'poor' to 'excellent' (Figure 1). Overall, 57% perceived

their general health to be excellent or very good, a further 34.5% perceived it

as good and 8.6% responded with 'fair' or 'poor'. Twice as many men (22%)

as women (10%) reported excellent health, a gender difference reflected in

responses to other measures of physical vitality reported below.

11

Figure 1: General health by gender

General Health (One-Item Measure)

50

45

40

35

Percentage

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Poor

Fair

Good

Very good

Excellent

Genral Health

Males

Females

4.3.2. Sleep and Nutrition

About 22.5% of students got less than seven hours sleep on week nights,

with 6% reporting less than six hours per night. More commonly, students

described having seven (38.8%) or eight hours (32.6%) sleep per night

during the week. There was a tendency to catch up on sleep at the weekend,

with 40.7% reporting getting nine hours or more a night.

Students reported on the typical number of fruit and vegetables consumed

each day. Nearly one-fifth (19.4%) reported consuming less than the

recommended five portions or more per day. A slightly larger proportion of

students (23.6%) reported consuming five portions only. This represents over

40% of the sample who consumed less than or just about the minimum

advised number of portions.

4.3.3. Mental Health

Almost two-thirds of students (65.8%) reported their mental health as "very

good" or "excellent" on a one-item, five-point measure ("How would you rate

your own mental health?". This is somewhat higher than the percentage who

reported comparable levels of physical health (57%). Approximately 11% of

the sample rated their mental health as fair or poor (Figure 2). There was a

12

significant gender difference in mental health self-ratings, reflected in the

proportions reporting excellent mental health by (males: 31%, females:

19%).

Figure 2: Self-rated mental health by gender

Mental Health (One-Item Measure)

50

45

40

35

Percentage

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Poor

Fair

Good

Very good

Excellent

Self-Reported Mental Health

Males

Females

4.3.4. Stress Perceptions

The students were asked how often they were stressed, in relation to 12

different sources of stress that had been identified in the CLAN survey of Irish

third level institutions (Hope et al., 2005). The 12 items are scored on a fourpoint scale ('never' to 'very often' stressed). Higher scores indicate higher

frequency of self-reported stress. Item responses had acceptable internal

reliability (Cronbach‟s α: 0.80, 95% CI =.78-.82). Responses can be assessed

individually by item or as a total stress score. Males reported a significantly

lower total score than females on the stress perceptions measure (mean

score of 24.0, SD: 5.9, compared with 25.7, SD: 5.3).

The most commonly reported sources of feeling 'often' or 'very often' stressed

were exams, subject-specific demands, studies in general, and financial

problems. Table 7 illustrates the responses in terms of these more extreme

response options on the four-point scale.

13

Table 7: Percentage reporting feeling 'often' or 'very often' stressed, by item

and gender.

Males

Females

Exams

Subject-specific demands

Studies in general

65.4

50.5

54.0

78.6

67.2

64.6

73.2**

60.4**

60.3**

Financial situation

Family situation

Living situation

41.9

16.7

18.8

50.4

22.4

25.8

47.0**

20.1*

23.0

Relationships

21.7

Competition at college

16.7

Anonymity at college

15.8

Circle of friends

13.5

Illness

10.8

Sexuality

5.3

* χ2, significant between gender (p<.05)

** χ2, significant between gender (p<.01)

20.4

26.2

16.8

17.8

11.8

3.2

20.9

22.4**

16.4

16.0*

11.4

4.0

College Studies

Living Conditions

Personal & Interpersonal

Total

Mean scores for the stress items ranged from 3.0 (SD: 0.8) out of 4.0, for the

item on exams, to 1.3 for the item on sexuality as a stressor (SD: 0.6). The

items related to university courses were reported as the most common

sources of stress, followed by living conditions, and personal or interpersonal

stressors. Gender differences in mean scores were particularly strong in

respect of college studies, finances and competition at college.

4.3.5. Physical and Mental Well-Being

Two multi-item measures of health and well-being are reported on here.

These are sub-scales of the SF-36 assessment tool. The SF-36 is used

extensively internationally and across population groups. The two scales are

the energy and vitality index (EVI) (Cronbach‟s α: 0.82, 95% CI = 0.80-0.84)

and the mental health index (MHI-5) (Cronbach‟s α: 0.84, 95% CI = 0.820.86).

Table 8 describes the SF-36 items individually, highlighting scores on the sixpoint scale by gender. Mean scores have been reversed where appropriate

(e.g., 'worn out') so that in all cases, higher scores indicate positive

responses. Females reported lower scores on physical well-being items for

energy and tiredness. Significant differences were noted on three of the five

mental health well-being items. Males reported higher levels of mood (i.e.,

less 'down') and a greater sense of calm. Scores on individual items can be

converted into a 0-100 score for each scale, with significant gender

differences noted in total scores as well as well as in individual item scores.

14

Table 8: SF-36 energy and vitality and mental health scores by gender

Energy and Vitality (EVI)

Males

Females

Total

Full of life

Energy

Worn outa

Tireda

4.1

3.9

4.1

3.7

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.3)

(1.2)

3.9

3.6

3.9

3.3

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.2)

4.0

3.7

4.0

3.5

(1.1)

(1.2)**

(1.2)*

(1.2)**

Nervousa

Down in the dumpsa

Calm and peaceful

Downhearted and bluea

Happy

4.5

5.1

3.9

4.6

4.4

(1.3)

(1.2)

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.1)

4.4

4.8

3.6

4.4

4.3

(1.3)

(1.2)

(1.1)

(1.1)

(1.1)

4.5

4.9

3.7

4.5

4.3

(1.3)

(1.2)**

(1.1)**

(1.8)**

(1.1)

Mental Health (MHI-5)

Total Scale Scores

EVI Score (0-100) 59.3 (19.3)

53.6 (19.1) 55.9 (19.4)**

MHI-5 Score (0-100) 70.1 (18.7)

65.7 (18.0) 67.5 (18.4)**

*Significant between gender (p<.004)

**Significant between gender (p<.001)

a

Item cores reversed, higher numbers indicate more positive scores for all items

In common with the findings of the SLÁN study of a representative sample of

Irish adults, male students had higher scores than female students on both

SF-36 scales. However, reported energy / vitality and mental health were

relatively low compared with the recent SLÁN population survey and

international studies (e.g., Morgan et al., 2008) (Table 9). Mean scores by

male students on the physical vitality scale lagged 13 points below the

population average in the SLÁN survey on the 0-100 scale, and 12 points

lower on the mental health scale. Female survey respondents were 15 points

below the female population norm on the physical vitality scale, and 15 points

lower on the mental health scale.

Table 9: Mean SF-36 scores on the energy and vitality / mental health scales

for SLS and SLÁN national surveys, by gender

Males

Females

Total

Energy and Vitality (EVI)

Mental Health (MHI-5)

59.3 (19)

70.1 (19)

53.6 (19)

65.7 (18)

55.9 (19)**

67.5 (18)**

Energy and Vitality (EVI)

Mental Health (MHI-5)

*Significant between gender (p<.005)

**Significant between gender (p<.001)

72.6 (19)

82.0 (16)

68.3 (19)

80.3 (16)

71.0 (19)**

82.0 (16)**

SLS

SLAN national survey

Relatively low SF-36 scores have been noted in previous research with UK

student populations (Stewart-Brown et al., 2000). The 1,200 students

surveyed in Stewart-Brown et al.'s study of three UK higher education

institutions reported relatively low scores on the vitality and mental health SF36 sub-scales. The mean vitality score for these students was 53.0, compared

with the UK national population norm for 18-35 year olds of 61.6. The

equivalent mean mental health sub-scale score for UK students was 65.6,

15

compared with the 18-35 year old norm of 72.3. Female students reported

lower scores, similar to the pattern identified in the responses to the SLS.

HIGHLIGHT: NUI Galway Students With a Disability

This study was carried out in 2012 by David Murray for a Higher Diploma in

Psychology research dissertation, in collaboration with the NUIG Disability

Support Service (DSS). Seventy-six students registered with the DSS were

surveyed for the study. The survey included the items on perceived stressors

and student engagement reported on in the SLS. This approach illustrates the

utility of using a similar set of indicators among particular sub-groups of the

student population in order to make comparisons with the rest of the

university community.

Students with a disability were more likely to report feeling

often or very often stressed by particular stressors, compared with

the SLS group. (73% by their studies in general, SLS: 60.3%; 85% by

subject-specific demands, SLS: 60.4%; 47% by competition at college,

SLS 22.4%; 79% by exams SLS: 73%; and 38% by illness, SLS:

11.4%).

Students with a disability were more likely to report that NUI

Galway emphasises spending time on academic work „quite a

bit‟ or „very much‟ (79%, SLS: 71.7%)

Students with a disability were less likely to report that NUI

Galway emphasises the support to succeed academically „quite

a bit‟ or „very much‟ (52.5%, SLS: 62.5%)

Students with a disability were more likely to report that NUI

Galway emphasises helping students to cope with nonacademic responsibilities quite a bit or very much (36.6%, SLS:

34.4%)

Students with a disability were less likely to report an

emphasis by NUI Galway on social thriving (39.4%, SLS: 51.5%)

Students with a disability were less likely to report that NUI

Galway emphasises attending academic events and activities

(41.4%, SLS: 61.2%)

This survey also asked about perceptions of the disability support. A high level

of satisfaction with disability support services (including assistive technology

services) was reported. However, the items on stressors and student

engagement indicate that NUI Galway students with a disability may perceive

more challenges to having a successful university experience, compared with

others.

16

4.6. SEXUAL HEALTH

Almost six out of ten of all students (59%) reported being sexually active in

the last month (males: 64%; females: 55%). When asked whether a condom

had been used on the last occasion of having sex, 68% said yes, 20% said

no, and the remaining 12% chose the „not applicable‟ option. The most

common reasons reported for not using condoms were being in a

monogamous relationship (13.8% of the sample), impaired judgement due to

alcohol or drugs (7.9%), and loss of sensation (6.9%, with more males

reporting this item, 12.1% males to 3.4% females). A quarter of students or

their partners had used emergency contraception at least once. There was a

significant difference in reporting by gender (males: 16%, females: 32%),

implying that many males were unaware of their sexual partners' use of

emergency contraception.

4.7. SUBSTANCE USE – TOBACCO AND DRUGS

One of the aims of the Student Lifestyle Survey was to assess how students

were using alcohol, tobacco, and drugs such as cannabis, Ecstasy and

cocaine. Particular attention is paid to depicting alcohol consumption patterns,

following the description of self-reported use of tobacco and illicit drugs.

4.7.1. Tobacco

Nearly one in four students (23%) reported being current smokers, with

males significantly more likely to report this status (males: 25%; females:

21%, p = .04). Students classified as current smokers were those who

reported smoking 'regularly' or 'occasionally (usually less than once a day)'.

Some 65% of students had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lives, with

significantly more females reporting this (males: 60%; females: 69%).

4.7.2. Illegal Drugs - Cannabis

Cannabis was by far the most common illegal drug reported by students. Fifty

per-cent indicated they had taken cannabis at least once in their life (females:

47%; males: 56%). Almost a fifth (18%) had taken the drug more than 20

times, with a significant gender difference (males: 25%, females: 12%). Onethird of participants (34%) reported taking cannabis at least once in the past

twelve months. There was a gender difference in reported cannabis use in the

past year, with 41.3% of males and 29.2% of females indicating they had

taken the drug (see Table 10 below). Of those who reported using cannabis

in the past year, 60.4% used it three or more times, making it the illegal drug

with the most frequent overall usage. Fourteen per-cent of the sample

reported taking the drug in the past 30 days, while 5% of males and 2% of

females using it ten or more times in the past 30 days.

Some 24% (n=207) of students responded to all five questions on the

Severity of Dependence Scale used to assess cannabis use (Cronbach‟s α: .84,

95% CI = 0.80-0.87; Martin et al., 2006). About 7% of these students

(males: 10%, females 4%) were above the cut-off score of 3 that is indicative

17

of dependence. For the purposes of the analysis, we identified relatively

frequent cannabis users as students who reported its use six times or more in

the past 12 months and who completed the cannabis dependence scale.

Considering these students only, 14% „sometimes‟ or „often‟ thought their

cannabis use out of control, 3% indicated it to be 'quite difficult' or

'impossible' to stop using the drug, 5% reported feeling anxious or nervous at

the prospect of missing a smoke, and 7.6% reported wishing they could stop.

No significant gender differences were noted on responses to the cannabis

dependence scale.

4.7.3. Illegal Drugs Besides Cannabis

Students were asked about use of other illegal drugs in the last 12 months.

Ecstasy was the second most commonly used drug after cannabis, albeit with

a much lower prevalence (ecstasy: 9%; cannabis: 34%). The next most

common drugs reported were cocaine (7%), salvia (6%) and magic

mushrooms (5%) (Table 10).

Table 10: Illegal drug use in past 12 months, by gender and frequency of use

Males

Females

Cannabis

41.3

Ecstasy (E, XTC)

12.9

Cocaine (Coke, Crack)

8.9

Salvia, BZP

10.9

Magic Mushrooms (Mushies,

peyote)

8.4

Amphetamine (Speed, Whizz,

uppers)

4.5

LSD (Acid, Trips)

3.9

Tranquillisers/sedatives

2.1

Stimulants (Ritalin) without

prescription

2.4

Solvents (Gas, Glue)

1.2

Heroin (Smack, Skag)

0.6

a

vs. „once or twice‟ among users of the drug

*Significant between gender (p<.05)

**Significant between gender (p<.01)

Total

29.2

5.9

5.1

2.7

34.1**

8.7**

6.7

6.0**

% users

taking drug

3+ times in

past year

60.4

47.2

21.8

32.7

2.3

4.8**

12.8

3.1

1.2

2.1

3.7

2.3*

2.1

13.3

15.8

17.6

0.6

1.0

0.4

1.3

1.1

0.5

18.2

22.2

25.0

With the exception of cannabis, the frequency of drug use was usually

reported as „once or twice‟ in the past twelve months. By comparison, 60% of

cannabis users reported using it „three or more times‟. Ecstasy was next most

frequently used drug, with nearly half of users (47%) in the past year

reporting using it three times or more. There were some gender differences

besides those already reported on cannabis use. Males were also more likely

to report using Ecstasy, Salvia / BZP, magic mushrooms, and LSD, although

the prevalence of use of these drugs was relatively low.

18

4.8. ALCOHOL

4.8.1. Drinking Habits: Frequency, Quantity and Beverage Type

About 73% of students had consumed alcohol during the last week and 91%

in the last month. Some 6% were non-drinkers, reporting that they never had

alcohol beyond sips and tastes (5%) or did not have a drink in the last twelve

months (<1%). Although non-Irish nationals were a relatively small

proportion of the participant group (5.6%), they represented 28% of the nondrinker group.

An average of 14 standard drinks were consumed per week, with males

reporting an average of 17 standard drinks and females an average of 12

standard drinks. One-third of men reported drinking more than the

recommended limit of 21 standard drinks per week, compared with 39% of

women drinking more than their recommended limit of 14 standard drinks.

The students were asked about their consumption of several types of drink,

allowing us to estimate the breakdown of drinking by beverage. The average

of 17 standard drinks consumed by males works out to 11 standard drinks in

beer / cider, one glass of wine, and five measures of spirits. The equivalent

figures for females are three standard drinks in beer / cider, three glasses of

wine, and six measures of spirits. Thus, spirits represent half of the alcohol

use reported by women compared with less than a third of the alcohol

reported by men.

Students were asked how often during the last 12 months they consumed (a)

beer/cider, (b) wine, and (c) spirits, from „every day‟ to „never‟. Less than 4%

drank any specific drink 4-5 days a week or more. Beer/cider consumption

once a week was reported by 51%, compared with 25% for drinking wine,

and 51% for spirits. Men were nearly twice as likely to drink beer as women

(males: 69.4%; females: 35.5%) at least once a week. This was a significant

difference, complemented by the greater likelihood of females reporting

drinking wine at least once a week (males: 18.8%; females: 29.1%). There

was no gender difference in likelihood of drinking spirits at least once a week

(males: 46.8%; females: 53.8%).

Binge drinking is defined in this report as drinking at least 75 grams of pure

alcohol on a given occasion (i.e., at least four pints of beer or equivalent).

Just under fifty per-cent (49.9%) were categorised as high frequency or

regular binge drinkers, defined here as reporting binge drinking once a week

or more (Table 11).

19

Table 11: Binge drinking frequency, by percentage and gender

Four times per week or more

Two-three times per week

Once a week

Once a month to once a week

Once or twice a year

Never / don't know a

ai

Includes non-drinkers

Males

3.3

29.3

29.0

20.1

7.0

11.3

Females

1.4

15.6

25.2

32.8

12.0

13.0

Total

2.2

21.2

26.6

27.7

10.0

12.3

Taking just those students who drink, more than half (53%) reported binge

drinking at least once a week (Figure 3). Men (66%) were significantly more

likely than women (44%) to report regular binge drinking at this frequency.

Figure 3: Frequency of binge drinking by gender in the last 12 months,

among those who reported drinking alcohol.

Binge Drinking Frequency

35

30

Percentage

25

20

15

10

5

0

Never / Rarely

1 Month

2-3 Month

1 Week

2-3 Week

4+ Week

Frequency of Binge Drinking

Males

Females

4.8.2 Alcohol-Related Problems and Harms

Responses to the four-item RAPS scale (Rapid Alcohol Problems Screen)

showed that 52% of drinkers reported having felt guilt or remorse after

drinking, 28% failed to do things because of drinking, 60% had experienced

not remembering things they said or did, and 3% reported having a drink in

the morning (Table 12). Responding positively to any one of these items is an

indicator of an alcohol problem. Although men reported drinking more than

women, gender differences in responses to RAPS items were not marked.

20

Table 12: Percentage reporting experience of alcohol problems, by gender

Guilt or remorse after drinking

Not remember things you said or did

Failed to do things because of drinking

Drink in the morning

Total RAPS score (mean/SD)

*Significant between gender (p<.05)

**Significant between gender (p<.01)

Males

52.1

63.2

28.9

5.4

1.5 (1.1)

Females

52.5

57.8

27.4

1.7

1.4 (1.1)

Total

52.3

59.9

28.0

3.2**

1.4 (1.1)

The RAPS scale represents harmful outcomes of drinking in the form of

'alcohol problems'. The survey also included a further list of harms and risks.

These refer to harmful consequences or exposure to risk, as a result of their

own drinking or that of others (Table 13). Over four-fifths (84%) of students

who drank alcohol reported at least one of these (males: 88%; females:

82%). There was a particularly high prevalence of regret after drinking

(59%), missing school / work days (54%), and feeling the effects while at

work / college (50%). There were gender differences such as males being

more than twice as likely to report having gotten into a fight. As with most of

the findings, there were relatively few differences across year in college.

Table 13: Percentage reporting experiencing harms or risks due to one‟s own

drinking, by gender

Males

Females

Felt effects of alcohol while at

class/work

Missed class/work days

Harmed studies/work

50.6

49.3

49.8

59.5

42.7

50.5

39.2

54.1**

40.6

Regretted things said or done

Got into fight

Been in accident

58.5

17.4

16.1

58.9

9.3

12.0

58.8

12.5**

13.7

Money problems

Unintentional sex

Unprotected sex

22.5

15.2

11.4

17.9

12.0

8.2

19.7

13.3

9.5

Feel should cut down

Harmed health

34.8

34.5

30.1

26.9

32.0

30.0*

19.0

14.6

4.0 (3.0)

9.3

12.2

3.4 (2.8)

Academic performance

Acute harms

Personal harms

Chronic harms

Social harms

Harmed friendships

Harmed relationship / home-life

Mean number of harms (SD)

*Significant between gender (p<.05)

**Significant between gender (p<.01)

Total

13.1**

13.1

3.6 (2.9)**

The survey also included a set of items on harms and risks experienced as a

result of other people's drinking. Two-thirds of students who drank reported

experiencing at least one harm or risk because of someone else's drinking

21

(Table 14). The harm cited most often by both genders was verbal abuse

(males: 38%; females: 32%). Males were more likely to experience acute and

personal harms, whereas females reported arguments and relationship

problems more often.

Table 14: Percentage reporting experience of risks or harms due to other's

drinking, by gender

Males

Females

Was in a motor car accident

Was passenger with drunk driver

Been hit or assaulted

Been sexually assaulted

0.9

14.7

17.6

0.9

1.0

6.6

7.8

1.0

1.0

9.9**

11.8**

1.0

Had financial trouble

Been verbally abused

Had property vandalised

4.7

38.4

29.3

5.6

31.6

17.8

5.2

34.4*

22.5**

Had family/relationship difficulties

Had arguments with family/friends

about drinking

Mean number of harms (SD)

*Significant between gender (p<.05)

**Significant between gender (p<.01)

12.3

15.8

17.8

21.8

15.6*

19.4*

1.4 (1.4)

1.1 (1.3)

Acute harm

Personal Harm

Social Harm

Total

1.2 (1.4)**

4.9. STUDENT ENGAGEMENT

4.9.1. Self-determination of NUI Galway Students

Self-determination corresponds to the personal growth that might be

expected to arise as a part of the university experience. The Basic Needs

Satisfaction scale was used to assess the self-determination of students

(Gagne, 2003). Higher self-determination scores are indicative of positive

well-being. For instance, scores are negatively correlated with anxiety,

worrisome thinking, generalised anxiety, and feelings of social inadequacy

(Johnston & Finney, 2010). The scale includes three factors (Table 15):

Personal autonomy: Items that refer to freedom and inner direction.

Competence: Items on mastery, control over behaviour and task

performance.

Relatedness: Need for affiliation with other people.

High scores on the three factors assessed in the self-determination measure

indicate that psychological needs are perceived as being met. The university

experience should ideally contribute to all three factors, through growth of

knowledge and job skills, confidence in the ability to achieve valued goals,

and feeling connected to other people. Each factor showed good levels of

internal reliability. The total scale alpha was 0.88 (95% CI = 0.87-0.89), with

the alpha on each of the three factors ranging from autonomy (0.70, 95% CI

= 0.67-0.73) to competence (alpha: 0.71, 95% CI = 0.68-0.74), and

22

relatedness (0.84, 95% CI = 0.83-0.86). Each factor had different number of

items. Examination of mean item scores showed that satisfaction of the

relatedness need was highest (eight items, mean score: 5.6 on seven-point

scale). The mean item score for autonomy was next (seven items, mean item

score 4.9 out of 7.0), followed by mean scores on competence items (six

items, 4.5 out of 7.0).

There were no gender differences in responses to the self-determination

measure. The scores recorded are slightly lower than those found in two

recent surveys of approximately 4,000 students at a US university (Johnston

& Finney, 2010). Autonomy scores for NUI Galway students were marginally

lower (mean score of 34.8) than those reported in the two student surveys

Johnston and Finney conducted (mean scores: 35.6, 35.8). Competence

scores were lower in the NUI Galway sample (mean score: 27.5; US survey

groups: 32.0, 31.0), as were relatedness scores (NUI Galway: 44.6; US

survey groups: 48.0, 47.5).

Table 15: Mean score for each self-determination factor, by gender

Autonomy

Competence

Relatedness

Total score

Male

34.9 (6.3)

27.3 (5.7)

44.5 (7.7)

106.7 (16.9)

Female

34.8 (6.4)

27.7 (6.1)

44.7 (7.5)

107.2 (17.0)

Total

34.8 (6.4)

27.5 (5.9)

44.6 (7.8)

106.9 (16.9)

4.9.2. Expectations of Higher Education at NUI Galway

Students were asked about their motives and expectations for the university

experience as NUI Galway. This occurred using items taken from the

Shortened Experiences of Teaching and Learning Questionnaire. The items

were scored on a five-point scale ('very weakly/not at all' to 'very strongly').

Some 88% of students indicated they were 'fairly' or 'very strongly' motivated

to develop personally through the experience (Table 16). Nearly half (48%)

reported similar expectations for their sports and social life, and 11.2% fairly

or very strongly wondered why they ever came here. Women reported higher

levels of engagement in personal development, reflected in items on making a

difference in the world and becoming independent.

23

Table 16: Percentage reporting 'fairly' or 'very strongly' to student engagement

items, by engagement factor and gender

Focused on sports and social life

Hope to develop independence and confidence

Need qualification for good job

Wonder why I ever came here

Male

49.7

76.2

75.6

12.5

Hope to develop personally

Want to make a difference in the world

Want to study subject in depth

84.7

66.2

65.8

Intrinsic engagement sub-scale

a

Female

46.5

88.1

82.0

10.3

90.6

78.5

69.9

Total

47.7

83.2**

79.3

11.2

88.2

73.4**

68.2

Other three categories are „very weakly/not at all‟ „Rather weakly‟ and „Somewhat/not sure‟

*Significant between gender (p<.05)

**Significant between gender (p<.01)

4.9.3. Overall Experience at NUI Galway and Perceived Institutional

Emphasis

The NUI Galway student experience was assessed using one of the sections

validated in the US National Survey of Student Engagement (Kuh, 2001). The

section on the supportiveness of the campus environment comprises five

items scored on a four-point scale (Cronbach‟s alpha: .73, 95% CI = .70-.76).

Students were asked about the extent to which NUI Galway emphasizes

particular issues relevant to the student experience. Some 72% of students

reported that NUI Galway emphasizes academic work to students 'quite a bit'

or 'very much' (Table 17). Only 34% of students felt that the university

emphasized coping with non-academic responsibilities to the same extent.

There were some minor gender differences in ratings. More women rated

academic and on-campus participation as being emphasised quite a bit or

very much in the university. A single item was used to asses the quality of the

overall experience at NUI Galway. Almost 30% students described their

academic experience as excellent. Most found it to be good, while 16%

reported it as fair or poor (excellent: 29%; good: 55%; fair: 14%; poor: 2%).

Table 17: Percentage reporting 'quite a bit' or 'very much' in response to

items about 'what NUI Galway emphasises''

Spending time on academic work

Providing support for academic success

Helping cope with non-academic responsibilities

Supporting social thriving

Attending campus events and activities

a

Other categories are: „Some‟ and „Very little‟.

*Significant between gender (p<.05)

Male

69.9

63.5

33.4

54.0

57.1

Female

72.9

61.7

35.1

49.8

64.1

Total

71.7*

62.5

34.4

51.5

61.2*

4.9.4. Awareness and Use of Student Services

Students were asked about their awareness and use of services (Table 18).

The Sports Centre had the highest usage, with more than half reporting using

it. Awareness of over 90% was reported for the Health Centre, with the

Health Promotion, Chaplaincy, Counselling and Careers advisory services also

24

achieving very high awareness. Gender differences in service awareness and

usage were noted, with males more likely to use the Sports Centre and

Disability service. Women were more likely to report using the Health Centre

and Counselling Service.

Table 18: Percentage reporting awareness and use of student facilities and

services, by gender

Awareness / Use

Not aware of it

Know of it, but haven't

Already used it

Health centre

Not aware of it

Know of it, but haven't

Already used it

Health promotion Not aware of it

Know of it, but haven't

Already used it

Chaplaincy

Not aware of it

Know of it, but haven't

Already used it

Disability support Not aware of it

Know of it, but haven't

Already used it

Counselling

Not aware of it

Know of it, but haven't

Already used it

Careers advisory Not aware of it

Know of it, but haven't

Already used it

*Significant between gender (p<.05)

**Significant between gender (p<.01)

Sports centre

used it

used it

used it

used it

used it

used it

used it

25

Males

1.2

37.7

61.1

9.1

47.0

43.9

23.9

63.9

12.2

13.2

75.2

11.6

28.0

66.5

5.5

12.6

80.0

7.4

13.1

66.5

20.4

Females Total

2.3

1.9**

54.1 47.4**

43.6 50.7**

4.4

6.3**

38.9 42.2**

56.7 51.5**

19.1 21.0

68.3 66.5

12.6 12.4

13.3 13.2

75.4 75.3

11.3 11.5

25.8 26.7*

72.3 69.9*

1.9

3.4*

6.3

8.8**

83.6 82.2**

10.1 9.0**

9.5

10.9

65.1 65.7

25.4 23.4

HIGHLIGHT: NUI Galway Students Who Volunteer

This research was carried out in 2012 by Marese O'Brien for a MSc in Health

Psychology research dissertation, and used several of the same measures

included in the Student Lifestyle Survey. Two surveys were carried out. One

was a follow-up survey with persistent volunteers, comprising 80 students

who had been volunteering in November 2010 and were still doing so in

Spring 2012. These students were now in 2nd / 3rd year or in postgraduate

study. The second survey was a cross-sectional survey of students engaged in

volunteering, both on- and off-campus. The demographic profile of this latter

group of 230 volunteers was more directly comparable to the SLS

respondents, with one-quarter in first year at college.

The surveys of volunteers indicated some important differences with the SLS

findings for the general undergraduate population.

Volunteers were more likely to report very good or excellent

general health (69% of persistent volunteers, 71.6% of the larger

cross-section, and 57% of SLS respondents)

Volunteers were less likely to have had a drink in the past

week (persistent volunteers 60.3%, compared with 68.4% of the

larger volunteer group, and 73% of the SLS respondents)

Volunteers reported lower levels of binge drinking (20.6% of

persistent volunteers reported binge drinking once a week or more,

38.5% once a month to once a week; 35.2% of the larger group of

volunteers reported binge drinking once a week or more, 31.8% once

a month to once a week; compared with the equivalent SLS figures of

50% for binge drinking once a week or more, 27.7% once a month to

once a week)

Volunteers reported fewer alcohol-related harms (44.6% of

persistent volunteers, 49.2% of larger volunteer group, and 58.8% of

SLS group reported experiencing regret following drinking; 20.3% of

persistent volunteers, 36% of larger volunteer group, and 40.6% of

SLS respondents reported that drinking had harmed their work or

studies; 14.9% of persistent volunteers, 33.1% of larger volunteer

group, and 30% of SLS respondents reported that alcohol had harmed

their health; 28.4% of persistent volunteers, 39.8% of larger volunteer

group, and 49.8% of SLS respondents reported having felt the effects

of alcohol while at work or in class)

26

5.1. PROFILE OF STUDENTS WITH HIGH RISK DRINKING PATTERNS

5.1.1. Analysis of Respondents by Drinking Pattern

Binge drinking has been associated with higher rates of harmful or risky

consequences of alcohol use in previous research. In the SLS survey, binge

drinking is defined as consumption of 75 grams or more of alcohol on a single

occasion (eight or more standard drinks, e.g., four pints of beer). Statistical

analyses were used to assess high frequency binge drinkers relative to other

drinkers. Non-drinkers (6%) are also included in several analyses where

applicable. Students were classified as high frequency or regular binge

drinkers if they reported binge drinking once a week or more. Regular binge

drinkers reported consuming an average of 19.3 standard drinks per week,

compared with 11.5 drinks among other drinkers.

5.1.2. Weekly time allocation and drinker status

Table 19 compares high frequency binge drinkers, other drinkers and nondrinkers in terms of weekly time allocation. Significant differences were found

in time spent studying and in class. Regular binge drinkers spent significantly

less time studying than others. At 24.9 hours, the length of the academic

week was significantly shorter for regular binge drinkers compared with other

drinkers (30.6 hours).

Table 19: Mean number of hours allocated to academic and paid work per

week, by drinking pattern

Regular

binge

drinkers

Classes/tutorials

16.5

Personal study (not exam time)

8.4

Paid work (just those working)

13.2

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

Other

drinkers

Nondrinkers

Total

17.7

12.9

12.2

20.1

13.0

12.9

17.3**

10.6**

12.7

Time allocation to extracurricular activities was considered in relation to binge

drinker status (Table 20). Sports participation was represented through time

spent playing sport and time involved in sports clubs. The other

extracurricular activities were volunteer work and being active in university

societies. Participation in sports accounted for more time than the other three

categories combined. Spread across participants, extracurricular activities

accounted for a rather low weekly time allocation. On average, students

contributed less than 30 minutes per week to volunteering. Non-drinkers

reported spending more time in society activities compared with the two other

groups.

27

Table 20: Mean number of hours allocated to extracurricular activities per

week, by drinking pattern

Regular

Other

binge

drinkers

drinkers

Playing sports

2.7

2.3

Sports clubs

1.4

0.9

Societies

0.7

0.9

Volunteering

0.3

0.4

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

Nondrinkers

2.9

1.0

1.9

0.7

Total

2.5

1.0

0.9**

0.4

5.1.3. Self-reported academic performance and drinker status

An assessment of self-reported academic performance in the last year by

drinking pattern showed significant results. Table 21 sets out the percentage

of students in each category of performance. Regular binge drinkers reported

a significantly lower mark compared with other drinkers. The same tendency

was seen when regular binge drinkers were compared with non-drinkers,

although this difference was not statistically significant. It should be borne in

mind that information on academic marks was provided by students rather

than standardised information from the university.

Table 21: Percentage of students reporting categories of academic

performance, by drinking pattern

59% or less

60%+

Regular

binge

drinkers

46.6

53.4

Other

drinkers

Nondrinkers

39.1

60.9

31.6

68.4

5.1.4. Risk taking and drinker status

Regular binge drinkers reported greater incidence of risk taking behaviours

(Table 22). They were twice as likely to be users of tobacco (32% vs 15%)

and cannabis (47% vs 25%). Although equally likely to use condoms, regular

female binge drinkers were significantly more likely to report using emergency

contraception (45% vs 30%). Nevertheless, regular binge drinkers reported

significantly higher ratings on the one-item measure of mental health. There

was a non-significant difference in physical health ratings.

28

Table 22: Percentage of students reporting risk-related behaviours and

mental / physical health, by drinking pattern

Regular

Other

Total

binge

drinkers

drinkers

Current smokers

32.1

15.0

22.8**

Cannabis use in past 12 months

46.9

24.0

34.1**

Sexually active

61.9

58.5

60.3

Condom usea

79.0

74.3

76.9

b

Emergency contraception

29.4

22.1

25.3**

One-item mental health ratingc

68.8

57.9

65.7**

One-item physical health ratingc

59.8

54.7

57.0

a

Only those who answered yes or no to „use of condom‟ when last had sex

b

Only woman, who answered yes or no to „use of condom‟ when last had sex

c

Percentage reporting 'very good' or 'excellent' in response to the item

*Significant difference (p<.05)

**Significant difference (p<.01)

5.1.5. Adverse consequences of alcohol use and drinker status

Significant differences were noted in the prevalence of alcohol-related

problems assessed by the RAPS scale, as a function of binge drinker status

(Table 23). For example, nearly three-quarters of regular binge drinkers

reported having experiences similar to a black out (not remembering what

you have said or done).

Table 23: Percentage of students reporting alcohol problems on the RAPS

items, by drinking pattern

Guilt or remorse after drinking

Not remember things you said or did

Failed to do things because of drinking

Drink in the morning

Mean RAPS score (SD)

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

Regular

binge

drinkers

61.2

74.1

37.2

5.0

1.8 (1.1)

Other

drinkers

41.9

43.6

17.5

1.1

1.0 (1.1)

Total

52.3**

60.0**

28.1**

3.2**

1.4 (1.1)**

Similarly, a higher prevalence of alcohol-related harms was reported among

regular binge drinkers. Compared with other drinkers, these students were

twice as likely to report having missed school / work (70% vs 36%) and

having studies or work harmed through drinking (53% vs 27%) (Table 24).

Money problems, fights and accidents were much more likely among regular

binge drinkers.

29

Table 24: Percentage of students reporting personal harms in past 12

months, by type of drinking

Regretted things said or done

Missed school/work days due to alcohol

Felt alcohol effects while at work/class

Harmed work/studies

Felt you should cut down drinking

Harmed health

Money problems

Been in accident

Got into fight

Unintended sex

Harmed friendship or social life

Harmed relationship / home-life

Unprotected sex

Mean number of harms reported (SD)

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

Regular

binge

drinkers

70.6

69.9

61.5

52.9

43.1

34.4

27.5

20.3

18.4

17.9

17.5

15.6

13.2

4.6 (2.8)

Other

drinkers

45.4**

36.2**

36.6**

26.9**

19.4**

24.9**

10.5**

5.8**

6.1**

8.0**

8.3**

10.5*

5.5**

2.4 (2.5)**

A similar pattern was evident in harms reported as a result of other people's

drinking, albeit with less pronounced differences between regular binge

drinkers and other drinkers (Table 25). Regular binge drinkers were more

likely to report having been verbally abused (40% vs 29%), physically

assaulted (15% vs 8%) or to have been a passenger with a drunk driver

(15% vs 5%).

Table 25: Percentage of students reporting harms due to other people's

drinking, by drinking pattern

Been verbally abused

Had property vandalised

Had arguments with family and friends

Been hit or assaulted

Been a passenger with drunk driver

Had family and relationship difficulties

Had financial trouble

Been in a motor car accident

Been sexually assaulted

Mean number of harms reported (SD)

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

Regular

binge

drinkers

40.2

28.5

20.8

15.1

15.3

14.6

6.0

1.0

1.0

1.4 (1.4)

Other

drinkers

29.1**

16.3**

18.8

7.8**

5.0**

17.7

4.7

0.8

1.1

1.0 (1.3)**

5.1.6. Vitality, mental health and drinker status

Several important differences were identified in SF-36 physical vitality and

mental health sub-scale scores as a function of drinker status (Table 26).

30

Non-drinkers had the highest overall SF-36 scores, indicative of relatively

good adjustment relative to drinkers, and reporting higher energy levels in

particular.

Regular binge drinkers reported better physical vitality and mental health than

other drinkers. This finding is consistent with responses to the one-item

mental health and general health measures. The finding appears counterintuitive, given that binge drinking is associated with harmful outcomes, but is

consistent with qualitative studies in which student drinkers describe

perceived benefits from binge drinking.

Each SF-36 item was scored on a six-point scale, from 'none of the time' to

'all of the time'. Table 26 shows mean item scores (maximum of 6.0). Scores

have been reversed where appropriate (e.g., 'worn out'), so the higher scores

in the table always reflect more positive responses. Regular binge drinkers

reported higher scores than other drinkers on feeling “full of life”, "calm and

peaceful" and "down in the dumps".

SF-36 sub-scale scores can be calculated on a 0-100 scale for comparability.

These scores are reported in Table 26. Of the three groups, non-drinkers

reported the highest physical vitality scores and second-highest scores on the

mental health sub-scale. Regular binge drinkers reported the second-highest

physical vitality scores and highest mental health levels. From this

perspective, 'other drinkers' emerged as the least well adjusted group.

Table 26: Mean scores on SF-36 energy / vitality and mental health items, by

drinking pattern

Regular

binge

drinkers

Other

drinkers

Nondrinkers

Full of life

Energy

Worn out

Tired

4.1

3.8

4.0

3.5

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.3)

(1.2)

3.9

3.6

3.9

3.4

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.2)

4.2

4.3

4.1

3.6

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.2)

4.0

3.7

4.0

3.5

(1.1)*

(1.2)**

(1.2)

(1.2)

Nervous

Down in the dumps

Calm and peaceful

Downhearted and blue

Happy

4.6

5.0

3.8

4.5

4.4

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.1)

4.4

4.8

3.6

4.5

4.2

(1.3)

(1.2)

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.2)

4.4

4.7

3.9

4.3

4.5

(1.3)

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.3)

(1.1)

4.5

4.9

3.7

4.5

4.3

(1.3)

(1.2)*

(1.1)**

(1.2)

(1.1)*

Energy and Vitality (EVI)

Mental Health (MHI-5)

Total Scores

EVI 57.0 (19.0)

MHI-5 69.0 (18.2)

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

31

54.0 (20.0)

65.7 (18.5)

Total

60.7 (18.0) 55.9 (19.4)*

67.4 (19.4) 67.4 (18.5)*

5.1.7. Self-determination, student engagement and drinker status

Further corroboration of the findings concerning alcohol use, vitality and

mental health were found in perceptions of stress. Regular binge drinkers had

a lower mean stress score of 24.58 (SD = 5.54), compared with other

drinkers (25.55, SD = 5.53, p=0.01). Responses to the basic needs

satisfaction measure of self-determination showed that regular binge drinkers

reported higher scores (Table 27). Differences between regular binge drinkers

and other drinkers on individual self-determination factors were not

significant, except for a marginal difference in social relatedness. Differences

in self-determination of drinkers and non-drinkers were significant. The latter

group reported lower scores on autonomy, relatedness and total selfdetermination, although not on perceptions of personal competence.

Table 27: Mean scores on self-determination factors, by type of drinker

Regular

Other

binge

drinkers

drinkers

Autonomy

35.4 (6.1)

34.6 (6.5)

Competence

27.6 (5.8)

27.5 (6.2)

Relatedness

45.3 (7.3)

44.3 (8.0)

Total score

108.4 (16.1) 106.4 (17.3)

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

Nondrinkers

Total

32.2 (6.7)

26.4 (5.7)

41.0 (9.5)

99.6 (19.6)

34.8 (6.4)**

27.5 (5.9)

44.6 (7.8)**

106.9 (16.9)**

Student engagement ratings indicated differences related to binge drinker

status, but in the reverse direction to those described in relation to vitality,

mental health and self-determination. Non-drinkers had significantly higher

engagement scores than regular binge drinkers (Table 28). Compared with

the other two groups, regular binge drinkers had rated the item on wanting to

“make a difference in the world" significantly lower. Non-drinkers had higher

scores on the item referring to wanting to “study subject in depth”. Regular

binge drinkers reported significantly lower scores in intrinsic engagement, but

significantly higher scores on the item referring to “sports and social life”.

32

Table 28: Mean scores on student engagement items and factors, by drinking

pattern

Regular

binge

drinkers

Focused on sports and social life 3.6 (1.0)

Hope to develop independence and 4.2 (0.9)

confidence

Need qualification for good job 4.2 (1.0)

Wonder why I ever came here 1.8 (1.1)

Intrinsic engagement sub-scale

Other

drinkers

Nondrinkers

3.1 (1.1)

4.2 (0.9)

3.2 (1.1) 3.4 (1.1)**

4.3 (0.7) 4.2 (0.9)

4.1 (1.0)

1.9 (1.1)

4.2 (0.9) 4.2 (1.0)

2.1 (1.4) 1.9 (1.2)

Hope to develop personally 4.3 (0.8) 4.4 (0.7) 4.5 (0.7)

Want to make a difference in the 4.0 (1.0) 4.1 (0.9) 4.3 (0.7)

world

Want to study subject in depth 3.8 (1.0) 4.0 (0.9) 4.1 (0.9)

Intrinsic total score 12.1 (2.1) 12.5 (2.0) 12.9 (1.7)

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

Total

4.4 (0.7)

4.1 (1.0)**

3.9 (1.0)**

12.3 (2.1)**

5.1.8. Perceptions of the university by drinker status

There were relatively minor differences by drinker status in perceptions of

NUI Galway. Table 29 gives the mean item scores on a four-point scale from

'very little' to 'very much'. On the whole, average ratings equate to a

perception that the university provided 'some' or 'quite a bit' of support. The

lowest evaluation of NUI Galway was in relation to helping students cope with

non-academic responsibilities. Regular binge drinkers evaluated the university

more positively than other drinkers on items referring to coping with nonacademic responsibilities and support for social thriving.

Table 29: Mean scores on 'NUI Galway emphasises' items, by drinking pattern

Regular

binge

drinkers

2.8 (0.8)

2.7 (0.9)

Spending time on academic work

Providing support for academic

success

Help coping with non-academic

2.3 (0.9)

responsibilities

Supporting social thriving

2.6 (0.9)

Attending campus events and

2.7 (0.9)

activities

Total Score

13.1 (3.1)

*Significant between drinking pattern (p<.05)

**Significant between drinking pattern (p<.01)

Other

drinkers

Nondrinkers

Total

2.9 (0.8)

2.7 (0.9)

2.8 (0.8) 2.8 (0.8)

3.0 (1.0) 2.7 (0.9)

2.1 (0.9)

2.3 (0.9) 2.2 (0.9)*

2.4 (0.9)

2.7(0.9)

2.6 (0.9) 2.5 (0.9)**

2.8 (0.8) 2.7 (0.9)

12.7 (3.1) 13.4 (3.1) 13.0 (3.1)

5.2. Gender, Binge Drinker Status and Year in College

This section highlights differences noted when we analysed categories such

as gender and binge drinker status together. Males were more likely to report

regular binge drinking (66% of male drinkers, 44% of female drinkers). Male

33