Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I and Binding Proteins 1, 2, and 3... Transfer Pregnancies

advertisement

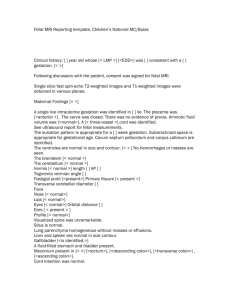

BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION 70, 430–438 (2004) Published online before print 15 October 2003. DOI 10.1095/biolreprod.103.021139 Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I and Binding Proteins 1, 2, and 3 in Bovine Nuclear Transfer Pregnancies1 Susan R. Ravelich,3 Bernhard H. Breier,2,3 Shiva Reddy,4 Jeffrey A. Keelan,3 David N. Wells,5 A. James Peterson,5 and Rita S.F. Lee5 Liggins Institute3 and Department of Pediatrics,4 Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand AgResearch,5 Ruakura Research Centre, Private Bag 3123, Hamilton, New Zealand ABSTRACT nome are possible and, thereby, also may provide better models for the treatment of human diseases [3–5]. Other potential applications include the conservation and preservation of endangered breeds [6] and species [7]. An increasing variety of mammalian species, including bovine [8], have been cloned using somatic cell NT [9– 12]. However, the efficiency of this technique is very low, with less than 6% of reconstructed NT embryos typically developing into live offspring [13]. Although major losses occur during the first 14 days after transfer of cloned blastocysts, the primary cause of subsequent fetal loss appears to be associated with functional placental deficiencies [14]. Placental abnormalities in cattle and sheep following transfer of cloned embryos have been recently documented and include increased placental weights and low placentome number [15, 16], enlarged umbilical vessels [8], and edematous membranes as well as increased allantoic fluid volume [8]. To our knowledge, the causes of these abnormalities remain unknown. Placental growth and differentiation are regulated by mechanisms that involve numerous endocrine and paracrine signals. Cytokines, such as members of the transforming growth factor (TGF) b family and members of the insulinlike growth factor (IGF) family, are actively synthesized by the ruminant placenta [17]. Systemic IGF-I in the fetus is an important determinant of the partitioning of nutrients between the fetus and placenta to favor fetal growth [18]. In the fetus, skeletal muscle and liver are major sites of IGF-I synthesis and potential sources of circulating IGF-I [19], although the placenta is actively involved in the regulation of IGF-I plasma concentrations [18]. The actions of the IGF family are regulated through their association with high-affinity binding proteins (IGFBPs) that determine their bioavailability. The IGFBPs also appear to mediate IGFindependent actions, such as inhibition or enhancement of growth and induction of apoptosis. The actions of IGFs are also regulated by IGFBP proteases, which affect the relative affinities of IGFBPs, IGFs, and IGF-I receptor for each other [20]. To date, six different high-affinity binding proteins (IGFBP-1 through -6) have been identified that specifically bind IGF-I and -II. Furthermore, IGFBP-1, -3, and -4 bind IGF-I and -II with similar affinities, whereas IGFBP-2, -5, and -6 preferentially bind IGF-II [21]. In bovine serum, the most abundant IGF carrier protein is IGFBP-3, which binds more than 95% of the IGF-I and -II in the circulation [20]. In the uterus, IGFBP-1 is found solely in the luminal epithelium, where it is reported to play an important role in regulating the transport of IGFs between the endometrium and the uterine lumen [22, 23]. In addition, IGFBP-1 is the predominant binding protein in amniotic fluid and a major In cloned pregnancies, placental deficiencies, including increased placentome size, reduced placentome number, and increased accumulation of allantoic fluid, have been associated with low cloning efficiency. To assess differences in paracrine and endocrine growth regulation in cloned versus normal bovine placentomes and pregnancies, we have examined the expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and -II and their binding proteins (IGFBP)-1 through -3 in placentomes of artificially inseminated (AI), in vitro-produced (IVP), and nuclear transfer (NT) pregnancies at Days 50, 100, and 150 of gestation. Fetal, maternal, and binucleate cell counts in representative placentomes were performed on Days 50–150 of gestation in all three groups. Increased numbers of fetal, maternal, and binucleate cells were present in NT placentomes at all stages of gestation examined. Immunolocalization studies showed that spatial and temporal patterns of expression of IGFBP-2 and -3 were markedly altered in the placentomes of NT pregnancies compared to AI/IVP controls. Concentrations of IGF-I in fetal plasma, as determined by RIA, were significantly higher (P 5 0.001) in NT pregnancies (mean 6 SEM, 30.3 6 2.3 ng/ml) compared with AI (19.1 6 5.5 ng/ml) or IVP (24.2 6 2.5 ng/ml) pregnancies on Day 150 of gestation. Allantoic fluid levels of IGFBP-1 were also increased in NT pregnancies. These findings suggest that endocrine and paracrine perturbations of the IGF axis may modulate placental dysfunction in NT pregnancies. Furthermore, increased cell numbers in NT placentomes likely have significant implications for fetomaternal communication and may contribute to the placental overgrowth observed in the NT placentomes. cytokines, female reproductive tract, growth factors, placenta, pregnancy INTRODUCTION The study and application of somatic cell nuclear transfer (NT) technology in mammals offers many benefits for research, biomedicine, and agriculture [1, 2]. In addition to providing a route for genetic modification in livestock and production of biopharmaceuticals, NT will extend the range of species in which desired genetic alterations of the geSupported by AgResearch and the Health Research Council of New Zealand. AgResearch also provided a Ph.D. stipend to S.R.R. Correspondence: Bernhard Breier, Liggins Institute, University of Auckland, 2-6 Park Ave, Grafton, Auckland, New Zealand. FAX: 0064 9 3737497; e-mail: bh.breier@auckland.ac.nz 1 2 Received: 13 July 2003. First decision: 28 July 2003. Accepted: 1 October 2003. Q 2004 by the Society for the Study of Reproduction, Inc. ISSN: 0006-3363. http://www.biolreprod.org 430 PARACRINE DISTURBANCES IN CLONED CATTLE PREGNANCY carrier protein in fetal serum, and its concentrations are increased in the maternal circulation during pregnancy [24]. In humans, IGFBP-1 is implicated to play a role in the abnormalities of placental development observed in preeclampsia [25]. The IGFBP-2 is primarily expressed by the maternal caruncular tissues, and its interaction with IGF-II may influence trophoblast function [22]. Circulating levels of IGFBP-2 are significantly increased in large-offspring fetuses following embryo culture. Liver expression is also markedly increased [26]. In the sheep, IGFBP-3 mRNA is expressed in the caruncular stroma, uterine luminal epithelium, and myometrium but is most abundant in the maternal blood vessel walls, where it may have an important role in angiogenesis [27, 28]. To our knowledge, no study has documented the spatial and temporal distributions of IGFs and IGFBPs in the cloned bovine placentome during early pregnancy. The aim of the present study was to determine if endocrine and paracrine factors involved in the regulation of normal placental growth, development, and function are dysregulated in cattle that are pregnant with embryos generated by NT. MATERIALS AND METHODS Investigations were conducted in accordance with the regulations of the New Zealand Animal Welfare Act of 1999. The generation of embryos for transfer to recipients or artificial insemination (AI) of the heifers was carried out in two separate experiments, conducted approximately 2 mo apart, with equal numbers of animals used for each experiment. All dams and recipients were 2-yr-old heifers of predominantly dairy or dairy-cross breeds. Oocytes for in vitro-produced (IVP) embryos or cytoplasts for NT were obtained from the same pool of ovaries collected from Friesian cows at the slaughterhouse. In vitro maturation of oocytes was carried out as previously described [8]. NT Embryos The methods used to generate the cloned (NT) embryos have been described previously [8]. An ovarian follicular cell line (EFC) derived from a 4-yr-old Friesian dairy cow and demonstrated to be totipotent following NT, as described by Wells et al. [8], was used in the present study. Donor cells used for NT had been previously cryopreserved and were obtained after at least nine cell passages in culture. Cells were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium and F12 (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS; Invitrogen) and sodium pyruvate to a final concentration of 1 mM. To induce the cells into a quiescent state, the FCS concentration in the medium was reduced to 0.5%, and the cells were cultured for a further 9– 11 days before being used for NT. After injection of the donor cells into the perivitelline space between the zona pellucida and the cytoplast, electrically mediated cell fusion was performed at 22–24 h after the start of maturation. Two direct current electrical pulses of 2.25 kV/cm for 10 msec each were delivered to individual, manually aligned donor cell-cytoplast couplets in a fusion chamber comprising two parallel electrodes spaced 500 mm apart and in 0.3 M mannitol-based buffer [8]. Successfully fused reconstructed embryos were activated 27–28 h after the start of maturation using a combination of 5 mM ionomycin (Sigma, Sydney, Australia) for 4 min followed by incubation in 2 mM 6-dimethylaminopurine (Sigma) for a further 4 h. After activation, in vitro culture was carried out essentially as described previously [29] in a biphasic AgResearch Synthetic Oviduct Fluid medium (AgR SOF; AgResearch, Hamilton, New Zealand). This medium was replaced on Day 4 of culture with fresh AgR SOF containing 10 mM 2,4-dinitrophenol as an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation [30]. The fatty acid-free bovine albumin (8 mg/ml) in the AgR SOF was ABIVP (ICP Bio, Auckland, New Zealand). On Day 7 postfusion, 49 NT embryos judged to be of suitable quality by a subjective grading system were transferred into recipient heifers. IVP Embryos In vitro-matured oocytes were fertilized with frozen-thawed spermatozoa in 50-ml drops under oil for 24 h as described previously [30]. The frozen semen used was obtained from the same Friesian bull that sired the 431 dairy cow from which the EFC cells were isolated. After fertilization, the zygotes were cultured as described for NT embryos. On Day 7 after fertilization, embryos of suitable quality were transferred to recipients. Artificial Insemination Twenty-one Friesian heifers were synchronized for estrus using intravaginal CIDR progesterone-release breeding devices (Pharmacia Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand) inserted for 12 days. On Day 8, all heifers were injected with 1 ml of estrumate (Schering-Plough, Union, NJ), and the CIDR devices were withdrawn after a further 4 days. The mean onset of estrus was approximately 48 h later. Approximately 12 h after the onset of estrus, frozen-thawed semen obtained from the same bull described above was used for AI. Recipients for IVP or NT Embryos Friesian or dairy crossbred heifers (n 5 70) were synchronized by a single 12-day CIDR breeding device concurrent with those heifers used for AI as described above. On the seventh day after observed estrus, 19 single-IVP and 49 single-NT embryos were transferred nonsurgically into the uterine lumen ipsilateral to the corpus luteum of each heifer. Pregnancy Monitoring From Day 40 of gestation until slaughter, pregnancy establishment and rates in all heifers were determined by monthly transrectal ultrasonographic examination using a Piemed 200 scanner with a linear 3.5- to 5-MHz rectal probe (Philip-sweg, Maastricht, The Netherlands). Fetal heartbeats were recorded from Day 60 onward. On Day 40, only the presence of a gestation sac was recorded. Tissue and Fluid Collection Maternal blood samples were obtained from the tail vein during ultrasound scanning. A sample of pregnant animals from each group was slaughtered on Days 50, 100, and 150 of gestation, and the reproductive tracts were collected and transported to the laboratory within 1 h. Caruncles were removed and trimmed of their associated membranes. Fetal fluids (amniotic and allantoic) were collected at all three gestation intervals, and fetal blood was collected at Day 150. Fetal fluids and serum were stored at 2208C pending analysis. Both fetal and maternal cotyledon tissues and tissue from intact placentomes were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in formalin-buffered PBS. Immunohistochemistry Two placentomes from each heifer were removed and placed in formalin-buffered PBS for sectioning, staining, and subsequent histological and immunohistochemical analysis. Antibodies to IGF-I and -II as well as IGFBP-1, -2, and -3 were raised in rabbits against recombinant human (rh) IGF-I (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), rhIGF-II (Eli Lily and Company, Indianapolis, IN), ovine (o) IGFBP-1 (sequence amino acids 105–121; Gropep, Thebarton, Australia), and oIGFBP-2 and -3 purified from sheep serum (Gropep) [31–33]. Antibodies were localized in placentomes by immunoperoxidase staining employing the avidin-biotin complex (ABC) for immunostaining of paraffin-embedded sections (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Tissues were embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned (thickness, 5 mm), and mounted on chrome alum-coated slides. Tissues were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded alcohols. Endogenous peroxidase activity was depleted by incubation with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in methanol for 30 min at room temperature. Tissues were preincubated for 30 min with normal goat serum diluted 1:200 to block nonspecific binding, then incubated with the appropriate dilution of antiserum—IGF-I (1:1500), IGF-II (1:200), IGFBP-1 (1: 800), IGFBP-2 (1:800), and IGFBP-3 (1:600)—for 24 h at 48C. After primary antibody incubations, tissues were washed in PBS and incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G for 2 h at room temperature followed by streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate for 20 min each at room temperature. After a further PBS wash, the tissues were incubated in diaminobenzidine until a positive reaction was observed (20–90 sec). Normal rabbit serum and antiserum preabsorbed with excess antigen were used as negative controls. Neutralization of immunoreactivity was defined as a marked reduction in staining intensity in the presence of antigen. Slides were photographed at 4003 magnification. A double-blind procedure was used to assess immunohistochemical scores based on staining 432 RAVELICH ET AL. TABLE 1. Fetal, maternal, and binucleate cell numbers in AI, IVP, and NT placentomes on Days 50, 100, and 150 of gestation.a Gestational age 50 100 150 a b Group n AI IVP NT AI IVP NT AI IVP NT 31 20 62 24 24 36 30 24 48 Fetal cell number 48.8 49.6 68.2 47.1 48.1 69.6 48.9 49.5 68.3 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 0.6 1.0 0.8b 1.0 0.9 0.8b 0.9 0.7 0.7b Maternal cell number 75.0 73.3 101.0 70.6 68.4 96.9 65.8 71.5 96.6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 1.3 1.1 0.8b 1.3 1.7 1.1b 1.5 1.3 0.8b Binucleate cell number 8.3 8.2 21.9 7.5 7.8 20.2 7.7 7.7 20.2 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 1.8 1.4 3.0b 0.2 0.2 0.4b 0.2 0.2 0.4b Values are the mean 6 SEM. P # 0.001, NT versus AI/IVP. intensity (2, no staining; 1, minimal staining; 11, moderate staining; 111, moderate to intense staining; 1111, intense staining). Cell Count Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with methyl green nuclear counterstain to assess fetal and maternal cell numbers. Binucleate cell numbers were determined by immunostaining with bovine placental lactogen (bPL; a marker gene of binucleate cells) [34]. Antibodies to bPL (a gift from J.C. Byatt, Monsanto Animal Agriculture Group, St Louis, MO), were raised in rabbit against purified native bPL [35] and used at a final dilution of 1:10 000. The ABC method of immunostaining was employed as described above. Cell counting was performed using a double-blind procedure, and random fields were assigned. A standard grid was used over high-power-field microscopic views (1003 magnification). Six random fields were examined within a 1- 3 1-cm ocular grid per section. All fetal trophectodermal mononucleate and binucleate and maternal uterine epithelial cells were counted at Days 50, 100, and 150 of gestation. One representative slide from each placentome (two placentomes per cow) was assessed. Radioimmunoassays Levels of IGF-I and -II and IGFBP-1 in fetal and maternal serum and fetal fluids (amniotic and allantoic) were measured using specific RIAs [33]. The same primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were used for the RIAs (see above). Cold recoveries and parallelism were performed on all bovine fluids. The limits of detection for serum IGF-I and IGFBP-1 and for amniotic and allantoic fluid IGFBP-1 were 1.0, 1.0, 0.2, and 0.3 ng/ml, respectively. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were less than 10%. Assays for IGFBP-2 and- 3 were not available. Statistical Analysis Statistical analyses were carried out using a Sigma Stat (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA) package. Differences between groups were determined by parametric (one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey) tests. Data are shown as the mean 6 SEM. Statistical significance was accepted at P , 0.05. RESULTS Histological Examination The cellular morphology of AI/IVP versus NT placentomes was similar at Days 50, 100, and 150 of gestation. The bovine cotyledon consisted of numerous slender chorionic villi accommodated within the crypts of the uterine mucosa. Each villus was composed of a core of vascular mesoderm covered by a layer of cuboidal trophoblast cells, many of which were binucleated. The maternal epithelium was composed of cuboidal cells interspersed with low columnar cells having centrally located nuclei. The basic descriptions of the cytology of the maternal and fetal compartments are in general agreement with those described by Björkman [36]. Despite similar cytological appearance, a significant in- crease was observed in fetal, maternal, and binucleate cell numbers in NT placentomes compared with AI/IVP controls at all gestational ages examined (Table 1). Furthermore, binucleate cell counts at Days 50, 100, and 150 of gestation were almost threefold higher in NT placentomes than in AI/IVP placentomes. Immunostaining with bPL allowed easy visualization of binucleated cells (which stained dark brown in all placentomes examined at Days 50, 100, and 150) and allowed comparison of binucleate cell numbers between AI, IVP, and NT placentomes, as illustrated in Figure 1. Cell numbers remained relatively constant throughout gestation, although maternal cell numbers were consistently higher than fetal cell numbers in all groups from Days 50 through 150 of gestation. Immunolocalization of IGFBPs at Days 50, 100, and 150 of Gestation The presence of IGFBP-1 was found in the deep uterine glands of the maternal placentome. Fetal villi did not stain for IGFBP-1. Immunoperoxidase staining was of moderate intensity in all AI, IVP, and NT placentomes. Negative controls showed no staining. No differences were observed in the localization of IGFBP-1 or staining intensity in AI, IVP, and NT placentomes with advancing gestation. A representative photograph (from n 5 10 placentae) of IGFBP-1 staining at Day 50 of gestation is shown in Figure 2A. Localization and immunohistochemical scores are shown in Table 2. Expression of IGFBP-2 was localized to the deep stromal tissue of the maternal placentome in all groups examined (Fig. 2, B–F). Intensity of stromal staining was moderate in the AI placentomes at Days 50 (Fig. 2B) and 100 (Fig. 2D) of gestation, with no visible staining at Day 150 of gestation. Placentomes from IVP pregnancies showed similar staining patterns (not shown). In contrast, intense staining of the stroma was observed in the NT placentome (Fig. 2, C and E) at Days 50 and 100 of gestation. The deep uterine glands and apical and medial regions (Fig. 2E) of the stromal tissue were immunonegative for IGFBP2. Maternal crypt and fetal villous tissue was also immunonegative in AI, IVP, and NT placentomes. The AI, IVP and NT placentomes were immunonegative for IGFBP-2 at Day 150 of gestation. No staining was detected in negative controls (Fig. 2F). Localization of IGFBP-3 was found in both fetal trophectodermal and maternal uterine tissue in NT placentomes, with strong, generalized staining for the three gestational periods examined (Fig. 2, H, J, and L). Little or no staining was observed for IGFBP-3 in AI and IVP (not shown) placentomes at all stages of gestation (Fig. 2, G, I, PARACRINE DISTURBANCES IN CLONED CATTLE PREGNANCY 433 FIG. 1. Representative photograph comparing binucleate cell number in an AI placentome (A) and an NT placentome (B) at Day 100 of gestation following immunolocalization of bovine placental lactogen. Arrows illustrate binucleated cells. CV, Chorionic villi; IC, intercrypt column. Magnification 3400. and K). No staining was observed in the negative control (Fig. 2M). calization and degree of staining intensity. Negative controls showed no staining. Localization of IGF-I and -II on Days 50, 100, and 150 of Gestation RIA Data Generalized, moderate to intense staining for IGF-I was observed in both fetal villous and maternal stromal and epithelial tissue in all placentomes at all stages of gestation examined, with no apparent differences between the three groups (data not shown). The IGF-II immunoreactivity was similar to the observations for IGF-I in terms of both lo- Concentrations of IGF-I in fetal serum on Day 150 of gestation were significantly higher (P 5 0.001) in NT pregnancies (30.3 6 2.3 ng/ml; n 5 8) compared with AI (19.1 6 5.5 ng/ml; n 5 5) or IVP (24.2 6 2.5 ng/ml; n 5 3) pregnancies (Table 3). On Day 40, maternal serum concentrations of IGF-I in the three groups were similar (AI, 64.4 6 6.4; IVP, 70.5 6 9.8; NT, 62.8 6 4.8 ng/ml). Maternal 434 RAVELICH ET AL. PARACRINE DISTURBANCES IN CLONED CATTLE PREGNANCY concentrations were higher between Days 48 and 145 but were not different among groups. Amniotic and allantoic fluid concentrations of IGF-I were either at or below the limits of detection for the assay in AI, IVP, and NT fluids from Days 50 through 150 of gestation. Maternal serum concentrations of IGFBP-1 were similar in all groups from Days 40 to 145 of pregnancy. A slight effect of stage on maternal IGFBP-1 levels was observed in all groups examined. Concentrations of IGFBP-1 decreased slightly at Day 95, increased at Day 117, and decreased again at Day 145 of gestation. Allantoic fluid concentrations of IGFBP-1 were almost twofold higher in NT versus AI/IVP pregnancies at Day 50 of gestation. However, no differences in amniotic fluid IGFBP-1 concentrations were found at this time point. Both amniotic and allantoic fluid IGFBP-1 concentrations at Days 100 and 150 of gestation were similar in AI, IVP, and NT pregnancies. Amniotic fluid IGFBP-1 decreased over time in all groups, whereas allantoic fluid IGFBP-1 levels were higher at Day 50, decreased slightly at Day 100, and increased again at Day 150 of gestation. Both IGFBP-2 and -3 were not measured in the present study because of the unavailability of suitable antisera. Concentrations of IGF-II in fetal serum and in amniotic and allantoic fluid could not be determined because of poor recovery from plasma, amniotic, and allantoic fluids. DISCUSSION Evidence from morphological studies of cloned pregnancies suggests that abnormal placental growth, development, and function contribute to poor fetal viability in these pregnancies. Perhaps the most striking observation in many NT pregnancies is the presence of large placentomes [13, 37, 38]. Histological examination of NT placentas suggests that hyperplasia of the placentome may be a compensatory mechanism secondary to reduced placentome number or may arise from aberrations in trophoblastic cell differentiation and function [15, 39]. Histological examination of NT versus AI/IVP placentomes indicated that fetal and maternal cell numbers were significantly increased in NT versus AI/IVP placentomes, suggesting that a combination of both cotyledonary and caruncular abnormalities contributes to the aberrant development of the placenta. Furthermore, binucleate cell numbers were markedly increased in NT placentas to almost threefold that of AI and IVP placentas. This observation could be explained by increased binucleate cell formation and/or decreased rate of binucleate cell migration across the fetomaternal interface of the NT placenta. These findings augment earlier reports by Farin et al. [40], who observed increased volume densities of binucleate cells in bovine placentas produced in vitro (but not in the IVP embryos of the present study). Binucleate cells play a central role in formation of the placental syncytium and secretions at the fetomaternal interface that are crucial in maintaining pregb FIG. 2. Immunolocalization of IGFBP-1 (representative Day 50 photograph [A]) and IGFBP-2 in the AI placentomes at Days 50 (B) and 100 (D) of gestation and in the NT placentome at Days 50 (C) and 100 (E) of gestation. Immunolocalization of IGFBP-3 in AI placentomes at Days 50 (G), 100 (I), and 150 (K) of gestation and in the NT placentome at Days 50 (H), 100 (J), and 150 (L) gestation is also shown, as are representative IGFBP-2 and -3 negative controls (F and M, respectively). Arrows indicate uterine glands (A–E). FV, Fetal villi; S, stroma; ME, maternal epithelium; a, apical; m, medial. Magnification 3400. 435 nancy [41]. As such, the observed increase in cell numbers likely has significant implications for fetomaternal communication and may contribute to the placental overgrowth observed in the NT placentome; however, the mechanisms by which this occurs remain largely unknown. Various components of the IGF system have been localized to the bovine uterus and placenta, where they show spatial and temporal patterns of expression [42, 43]. In the placenta, the IGFs promote cellular mitosis and differentiation, migration and aggregation, as well as inhibition of apoptosis [23]. Variations in the pattern of expression of either IGF-I or -II have a range of effects on placental growth. Small placentas are found in IGF-II knockout mice, whereas mice that overexpress IGF-II exhibit placental edema [44]. Furthermore, disruption of the IGF-II receptor, with an associated reduction in IGF-II clearance, leads to placental hypertrophy [45, 46]. Many of these features have been reported in cloned animals [13, 15, 16]. In the present study, we have investigated the hypothesis that differences in the expression of IGFs and IGFBPs in NT pregnancies may be fundamental to the placental abnormalities that are seen in cloned cattle. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document differences in IGFs/IGFBPs in bovine NT pregnancies early during gestation. The results of the present study demonstrate that serum IGF-I levels were significantly increased in NT fetuses at Day 150 of gestation compared to IVP and AI controls. In contrast, Chavatte-Palmer et al. [16] found no difference in IGF-I concentrations in cloned calves compared to controls. However, IGF-I concentrations are dramatically reduced after birth [18]. A dominant influence on fetal IGF-I levels, at least during the later stage of gestation, is nutrient status, particularly glucose availability to the fetus [18]. Defects in energy metabolism, such as hyperinsulinemia and hypoglycemia, have been reported in a number of calves following NT [47]. Increased IGF-I levels in fetal serum therefore may reflect altered energy metabolism in NT fetuses, perhaps because of adaptations made by the conceptus to abnormal placental function. The liver is the major source of circulating IGF-I, and increased liver weights have been reported in cloned sheep [38] and cattle fetuses (unpublished data). Alterations in hepatic synthesis or clearance of IGF-I, perhaps induced by placental deficiencies, may give rise to the increased liver weights often associated with NT fetuses. Alternatively, elevated fetal IGF-I levels might cause disturbances in placental growth and development. Fetal IGF-I concentrations have been significantly and positively correlated with fetal weight and placental mass [48]. Recently, Gadd et al. [48] showed how such changes in placental mass are correlated with alterations in the pattern of expression of the IGF system within the uteroplacental unit of sheep. In the present study, maternal serum concentrations of IGF-I and IGFBP-1 were similar between groups, and no differences in amniotic fluid IGFBP-1 levels were observed. To the contrary, Bertolini and Anderson [37] reported increased maternal plasma concentrations of IGF-I and -II in IVP pregnancies throughout gestation, although no data were presented. Furthermore, those authors described alterations in the IGFBPs within amniotic and allantoic fluids of IVP pregnancies before Day 90 of gestation. Similarly, we observed significantly increased allantoic fluid IGFBP-1 concentrations at Day 50 of gestation in NT pregnancies. These findings are coincident with an increase in allantoic fluid volumes in Day 50 NT pregnancies (unpublished data). Allantoic fluid is normally absorbed by 436 RAVELICH ET AL. TABLE 2. Localization and immunohistochemical scores for Day-50, -100, and -150 placentae from AI, IVP, and NT cattle.a Treatment AI Ligand IGFBP-1 IGFBP-2 IGFBP-3 IGF-I IGF-II a IVP NT Gestation day F M F M F M Fetal tissue 50 100 150 50 100 150 50 100 150 50 100 150 50 100 150 2/1 2/1 2 2 2 2 2/1 2/1 1 111 111 111 111 111 111 11 11 2 11 11 2 2/1 2/1 1 111 111 111 111 111 111 2/1 2/1 2 2 2 2 2/1 2/1 1 111 111 111 111 111 111 11 11 2 11 11 2 2/1 2/1 1 111 111 111 111 111 111 2/1 2/1 2 2 2 2 1/11 1/11 1/11 111 111 111 111 111 111 11 11 2 1111 1111 2 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 Villi Villi Villi — — — Villi Villi Villi Villi Villi Villi Villi Villi Villi TABLE 3. IGF-I and IGFBP-1 concentrations in maternal serum and fetal fluids (amniotic and allantoic) as determined by RIA.a Day AI IVP NT 40 48 60 69 95 117 145 40 48 60 69 95 117 145 Maternal serum (ng/ml) 64.4 6 6.4(6) 70.5 6 9.8(5) 98.4 6 5.6(8) 84.9 6 6.3(5) 75.1 6 3.0(4) 92.0 6 9.6(4) 89.1 6 7.1(7) 124.4 6 7.5(4) 84.3 6 3.5(6) 89.9 6 16.3(3) 78.2 6 8.3(5) 80.7 6 9.1(4) 84.1 6 3.6(4) 97.1 6 13.3(4) 4.0 6 0.5(6) 6.1 6 2.2(5) 4.5 6 0.5(8) 5.3 6 1.49(5) 3.8 6 1.0(4) 4.9 6 1.8(4) 3.8 6 1.1(7) 4.9 6 1.8(4) 2.1 6 0.3(6) 1.9 6 0.3(3) 4.3 6 1.1(5) 6.4 6 2.7(4) 1.2 6 0.3(4) 1.3 6 0.1(4) IGFBP-1 50 100 150 Amniotic fluid (ng/ml) 1.20 6 0.30(5) 1.60 6 0.60(3) 1.20 6 0.20(3) 0.90 6 0.40(3) 0.40 6 0.10(4) 0.70 6 0.20(3) 0.90 6 0.10(9) 0.90 6 0.10(4) 0.70 6 0.10(7) IGFBP-1 50 100 150 Allantoic fluid (ng/ml) 0.90 6 0.10(4) 0.80 6 0.10(3) 0.50 6 0.20(4) 0.70 6 0.20(3) 1.00 6 0.01(4) 1.00 6 0.01(3) 1.40 6 0.10(9)b 0.90 6 0.80(3) 0.90 6 0.01(9) IGF-I IGFBP-1 b Maternal tissue Uterine glands Uterine glands — Uterine stroma Uterine stroma — Throughout uterus Throughout uterus Throughout uterus Throughout uterus Throughout uterus Throughout uterus Throughout uterus Throughout uterus Throughout uterus F, fetal; M, maternal; 2, no staining; 1, minimal staining; 11, moderate staining; 111, moderate to intense staining; 1111, intense staining. the placenta. However, in the case of NT pregnancies, fluid is retained, perhaps because of the inability of the lower number of caruncles to maintain the balance [49]. An alteration in the function of the allantoic membrane, perhaps because of altered hormonal status of the cow, also may contribute to hydrallantois [38, 50]. No differences of amniotic or allantoic IGFBP-1 concentrations were observed in NT versus AI/IVP at Day 100 or 150 of gestation. This may reflect a dilution of IGFBP-1 with increased fetal fluid volumes in NT pregnancies at later gestational stages. In addition to the systemic actions considered above, immunoperoxidase staining of IGFBPs in NT pregnancies showed significant differences compared to AI/IVP placentas, although staining of IGF-I and -II did not differ. The spatial and temporal patterns of IGF-I and -II expression a Localization Values are mean 6 SEM. P # 0.001, NT versus AI/IVP. 62.8 100.2 95.8 82.8 103.2 94.4 96.3 3.4 5.2 3.2 3.2 1.8 5.2 1.6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 4.8(14) 5.9(10) 9.7(9) 11.1(3) 9.4(5) 7.3(8) 11.6(6) 1.7(14) 0.8(10) 0.4(9) 0.4(3) 0.3(5) 2.2(8) 0.3(6) reported here are in agreement with studies described elsewhere [42, 43]. Whereas IGFBP-1 expression in AI, IVP, and NT placentomes was similar at Days 50, 100, and 150 of gestation, expression of both IGFBP-2 and -3 was significantly increased in placental tissues from NT pregnancies. Increased expression of IGFBP-2 and -3 in NT placentas may indicate either increased production or upregulation by other growth effectors. Signals for increased production of the binding proteins may emanate from the placenta in response to either altered availability of IGF-I and -II or upregulation by other cytokines and cell-cycle regulators, such as TGFb, retinoic acid, or p53 [51, 52]. However, we found no difference in immunoperoxidase staining of IGF-I and -II between NT and AI placentas. Increased retention of IGFs or reduced proteolysis and induction of IGF-independent action may reduce expression of IGFs, limiting their bioavailability. Martin and Baxter [53] showed that in T47D breast cancer cells transfected to overexpress IGFBP-3, the cell population changed from a state of relative cell-cycle arrest to one of insensitivity to the inhibitory effect of IGFBP-3, in which cell growth was uninhibited. Overexpression of IGFBP-2 and enhanced proliferation in Y-1 adrenocortical tumors via IGF-independent actions also have been described [54]. An alternative explanation is increased induction of the regulators of IGFBP2 and -3. Fanayan et al. [55] reported that IGFBP-3 inhibitory signaling requires an active TGFb signaling pathway. Conceivably, then, abrogation of this pathway may stimulate IGFBP-3 growth signaling effects. Consistent with this view, Kansra et al. [56] has shown that the induction of IGFBP-3 by TGFb is associated with enhanced growth in colon cancer. In summary, the results of the present study demonstrate that cell number is significantly increased in both fetal and maternal tissues of placentomes in NT pregnancies compared with AI/IVP controls. Increased production of IGFBP-2 and -3 in these pregnancies may provide a causal explanation for the increase in cell number and, potentially, increased placental size observed in NT pregnancies. Whether these factors are part of the cause of placental dysfunction or merely a consequence of abnormal placental development is yet to be established. PARACRINE DISTURBANCES IN CLONED CATTLE PREGNANCY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge Chris Keven and Janine Street for their technical assistance with the RIAs and Martyn Donnison for routine care of the animals used in the present study. REFERENCES 1. Colman A, Kind A. Therapeutic cloning: concepts and practicalities. Trends Biotechnol 2000; 18:192–196. 2. Yang X, Tian XC, Dai Y, Wang B. Transgenic farm animals: applications in agriculture and biomedicine. Biotechnol Annu Rev 2000; 5:269–292. 3. Harris A. Towards an ovine model of cystic fibrosis. Hum Mol Genet 1997; 6:2191–2194. 4. Wagner J, Thiele F, Ganten D. Transgenic animals as models for human disease. Clin Exp Hypertens 1995; 17:593–605. 5. Petters RM, Sommer JR. Transgenic animals as models for human disease. Transgenic Res 2000; 9:347–351. 6. Wells DN, Misica PM, Tervit HR, Vivanco WH. Adult somatic cell nuclear transfer is used to preserve the last surviving cow of the Enderby Island cattle breed. Reprod Fertil Dev 1998; 10:369–378. 7. Ryder OA. Cloning advances and challenges for conservation. Trends Biotechnol 2002; 20:231–232. 8. Wells DN, Misica PM, Tervit HR. Production of cloned calves following nuclear transfer with cultured adult mural granulosa cells. Biol Reprod 1999; 60:996–1005. 9. Wakayama T, Perry AC, Zuccotti M, Johnson KR, Yanagimachi R. Full-term development of mice from enucleated oocytes injected with cumulus cell nuclei. Nature 1998; 394:369–374. 10. Baguisi A, Behboodi E, Melican DT, Pollock JS, Destrempes MM, Cammuso C, Williams JL, Nims SD, Porter CA, Midura P, Palacios MJ, Ayres SL, Denniston RS, Hayes ML, Ziomek CA, Meade HM, Godke RA, Gavin WG, Overstrom EW, Echelard Y. Production of goats by somatic cell nuclear transfer. Nat Biotechnol 1999; 17:456– 461. 11. Polejaeva IA, Chen SH, Vaught TD, Page RL, Mullins J, Ball S, Dai Y, Boone J, Walker S, Ayares DL, Colman A, Campbell KH. Cloned pigs produced by nuclear transfer from adult somatic cells. Nature 2000; 407:86–90. 12. Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, McWhir J, Kind KL, Cambell KHS. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 1997; 385:810–813. 13. Hill JR, Burghardt RC, Jones K, Long CR, Looney CR, Taeyoung S, Spencer TE, Thopmson JA, Winger QA, Westhusin ME. Evidence for placental abnormality as the major cause of mortality in first trimester somatic cell cloned bovine fetuses. Biol Reprod 2000; 63:1787–1794. 14. Hill JR, Roussel AJ, Cibelli JB, Edwards JF, Hooper NL, Miller MW, Thompson JA, Looney CR, Westhusin ME, Robl JM, Stice SL. Clinical and pathologic features of cloned transgenic calves and fetuses (13 case studies). Theriogenology 1999; 51:1451–1465. 15. Hashizume K, Ishiwata H, Kizaki K, Yamada O, Takahashi T, Imai K, Patel OV, Akagi S, Shimizu M, Takahashi S, Katsuma S, Shiojima S, Hirasawa A, Tsyjimoto G, Todoroki J, Izaike Y. Implantation and placental development in somatic cell clone recipient cows. Cloning and Stem Cells 2002; 4:197–209. 16. Chavatte-Palmer P, Heyman Y, Richard C, Monget P, LeBourhis D, Kann G, Chilliard Y, Vignon X, Renard JP. Clinical, hormonal, and hematologic characteristics of bovine calves derived from nuclei from somatic cells. Biol Reprod 2002; 66:1596–1603. 17. Munson L, Wilhite A, Boltz VF, Wilkinson JE. Transforming growth factor beta in bovine placentas. Biology of Reproduction 1996; 55: 748–755. 18. Bauer MK, Harding JE, Bassett NS, Breier BH, Oliver MH, Gallaher BH, Evans PC, Woodall SM, Gluckman PD. Fetal growth and placental function. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1998; 140:115–120. 19. Yakar S. The role of circulating IGF-I: lessons from human and animal models. Endocrine 2002; 19:239–248. 20. Wetterau LA, Moore MG, Lee KW, Shim ML, Cohen P. Novel aspects of the insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Mol Genet Metab 1999; 68:161–181. 21. Reynolds TS, Stevenson KR, Wathes DC. Pregnancy-specific alterations in the expression of the insulin-like growth factor system during early placental development in the ewe. Endocrinology 1997; 138: 886–897. 22. Han VKM, Bassett N, Walton J, Challis JRG. The expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF-binding protein (IGFBP) genes 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 437 in the human placenta and membranes—evidence for IGF-IGFBP interactions at the fetomaternal interface. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:2680–2693. Han VK, Carter AM. Spatial and temporal patterns of expression of messenger RNA for insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in the placenta of man and laboratory animals. Placenta 2000; 21:289–305. Rajaram S, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in serum and other biological fluids: regulation and functions. Endocr Rev 1997; 18:801–831. Crossey PA, Pillai CC, Miell JP. Altered placental development and intrauterine growth restriction in IGF binding protein-1 transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 2002; 110:411–418. Young LE, Fernandes K, McEvoy TG, Butterwith SC, Gutierrez CG, Carolan C, Broadbent PJ, Robinson JJ, Wilmut I, Sinclair KD. Epigenetic change in IGF2R is associated with fetal overgrowth after sheep embryo culture. Nat Genet 2001; 27:153–154. Renfree MB. Implantation and placentation. In: Austin CR, Short RV (eds.), Reproduction in Mammals 2. Embryonic and Fetal Development, 2nd ed. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press; 1982: 26–69. Peterson AJ, Ledgard AM, Hodgkinson SC. Oestrogen regulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) and expression of IGFBP-3 messenger RNA in the ovine endometrium. Reprod Fertil Dev 1998; 10:241–247. Wells DN, Laible G, Tucker FC, Miller AL, Oliver JE, Xiang T, Forsyth JT, Berg MC, Cockrem K, L’Huillier PJ, Tervit HR, Oback B. Coordination between donor cell type and cell cycle stage improves nuclear cloning efficiency in cattle. Theriogenology 2003; 59:45–59. Thompson JG, McNaughton C, Gasparrini B, McGowan LT, Tervit HR. Effect of inhibitors and uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation during compaction and blastulation of bovine embryos cultured in vitro. J Reprod Fertil 2000; 118:47–55. Gallaher BW, Breier BH, Blum WF, McCutcheon SN, Gluckman PD. A homologous radioimmunoassay for ovine insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2: ontogenesis and the response to growth hormone, placental lactogen and insulin-like growth factor-I treatment. J Endocrinol 1994; 144:75–82. Gallaher BW, Breier BH, Keven CL, Harding JE, Gluckman PD. Fetal programming of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-binding protein-3: evidence for an altered response to undernutrition in late gestation following exposure to periconceptual undernutrition in the sheep. J Endocrinol 1998; 159:501–508. Bennet L, Oliver MH, Gunn AJ, Hennies M, Breier BH. Differential changes in insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins following asphyxia in the preterm fetal sheep. J Physiol 2001; 531:835– 841. Duello TM, Byatt JC, Bremel RD. Immunohistochemical localization of placental lactogen in binucleate cells of bovine placentomes. Endocrinology 1986; 119:1351–1355. Byatt JC, Eppard PJ, Veenhuizen JJ, Sorbet RH, Buonomo FC, Curran DF, Collier RJ. Serum half-life and in-vivo actions of recombinant bovine placental lactogen in the dairy cow. J Endocrinol 1992; 132: 185–193. Björkman NH. Light and electron microscopic studies on cellular alterations in the normal bovine placentome. Anat Rec 1969; 163:17– 29. Bertolini M, Anderson GB. The placenta as a contributor to production of large calves. Theriogenology 2002; 57:181–187. De Sousa PA, King T, Harkness L, Young LE, Walker SK, Wilmut I. Evaluation of gestational deficiencies in cloned sheep fetuses and placentae. Biol Reprod 2001; 65:23–30. Tanaka S, Oda M, Toyoshima Y, Wakayama T, Tanaka M, Yoshida N, Hattori N, Ohgane J, Yanagimachi R, Shiota K. Placentomegaly in cloned mouse concepti caused by expansion of the spongiotrophoblast layer. Biol Reprod 2001; 65:1813–1821. Farin PW, Stewart RE, Rodriguez KF, Crozier AE, Blondin P, Alexander JE, Farin CE. Morphometry of the bovine placenta at 63 days following transfer of embryos produced in vivo or in vitro. Theriogenology 2001; 55:320–321. Wooding FB. The role of the binucleate cell in ruminant placental structure. J Reprod Fertil 1982; 31:31–39. Wathes DC, Reynolds TS, Robinson RS, Stevenson KR. Role of the insulin-like growth factor system in uterine function and placental development in ruminants. J Dairy Sci 1998; 81:1778–1789. Robinson RS, Mann GE, Gadd TS, Lamming GE, Wathes DC. The 438 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. RAVELICH ET AL. expression of the IGF system in the bovine uterus throughout the oestrous cycle and early pregnancy. J Endocrinol 2000; 165:231–243. Gardner RL, Squire S, Zaina S, Hills S, Graham CF. Insulin-like growth factor-2 regulation of conceptus composition: effects of the trophectoderm and inner cell mass genotypes in the mouse. Biol Reprod 1999; 60:190–195. Eggenschwiler J, Ludwig T, Fisher P, Leighton PA, Tilghman SM, Efstratiadis A. Mouse mutant embryos overexpressing IGF-II exhibit phenotypic features of the Beckwith-Wiedemann and Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndromes. Genes Dev 1997; 11:3128–3142. Tanaka S, Oda M, Toyoshima Y, Wakayama T, Tanaka M, Yoshida N, Hattori N, Ohgane J, Yanagimachi R, Shiota K. Placentomegaly in cloned mouse concepti caused by expansion of the spongiotrophoblast layer. Biol Reprod 2001; 65:1813–1821. Wilson JM, Williams JD, Bondioli KR, Looney CR, Westhusin ME, McCalla DF. Comparison of birth weight and growth characteristics of bovine calves produced by nuclear transfer (cloning), embryo transfer and natural mating. Anim Reprod Sci 1995; 38:73–83. Gadd TS, Aitken RP, Wallace JM, Wathes DC. Effect of a high maternal dietary intake during mid-gestation on components of the uteroplacental insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system in adolescent sheep with retarded placental development. J Reprod Fertil 2000; 118:407– 416. Wintour EM, McFarlane A. Abnormalities of foetal fluids in sheep: two case reports. Aust Vet J 1993; 70:376–378. Peterson AJ, McMillan WH. Allantoic aplasia—a consequence of in 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. vitro production of bovine embryos and the major cause of late gestation embryo loss. In: Proceedings of the 29th annual conference of the Australian Society for Reproductive Biology; 1998; Perth, Australia. Abstract 4. Hwa V, Oh Y, Rosenfeld RG. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 and -5 are regulated by transforming growth factor-beta and retinoic acid in the human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line PC-3. Endocrine 1997; 6:235–242. Rajah R, Valentinis B, Cohen P. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-3 induces apoptosis and mediates the effects of transforming growth factor-b1 on programmed cell death through a p53- and IGF-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem 1997; 272:12181–12188. Martin JL, Baxter RC. Oncogenic ras causes resistance to the growth inhibitor insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 1999; 274:16407–16411. Hoeflich A, Fettscher O, Lahm H, Blum WF, Kolb HJ, Engelhardt D, Wolf E, Weber MM. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factorbinding protein-2 results in increased tumorigenic potential in Y-1 adrenocortical tumor cells. Cancer Res 2000; 60:834–838. Fanayan S, Firth SM, Butt AJ, Baxter RC. Growth inhibition by insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 in T47D breast cancer cells requires transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-b) and the type II TGF-b receptor. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:39146–39151. Kansra S, Ewton DZ, Wang J, Friedman E. IGFBP-3 mediates TGFb1 proliferative response in colon cancer cells. Int J Cancer 2000; 87: 373–378.