Afghanistan Reconstruction Vision JSCE

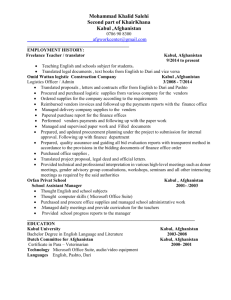

advertisement