ANCHOR GRAPHICS VOLUME 4 NO. 2

advertisement

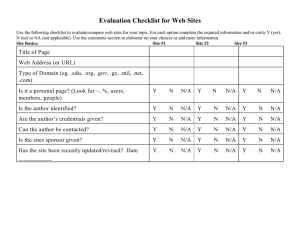

ANCHOR GRAPHICS A PROGRAM OF THE ART + DESIGN DEPARTMENT AT COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO VOLUME 4 NO. 2 WINTER 2010 2 ANCHOR GRAPHICS OUR MISSION Anchor Graphics is a not-for-profit printshop that brings together, under professional guidance, a diverse community of youth, emerging and established artists, and the public to advance the fine art of printmaking by integrating education with the creation of prints. CONTENTS 2 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR 3 RECENT EVENTS 4 RECENT EDITIONS 5 A PARADISE OF THE ORDINARY INDUSTRY OF THE ORDINARY 6 EL CORAZÓN DE LA OSCURIDAD 10 SLOW RELEASE 14 UPCOMING PROGRAMS DAVID JONES DON COLLEY GORDON BRENNAN & JOHN BROWN ON THE COVER: JOHANNA MUELLER, EXPLODE (DETAIL) RELIEF ENGRAVING WITH HAND COLORING 7” X 10”, 2010 FROM EXCHANGE 7 EXHIBIT LEFT: KRISTA HOEFLE UNTITLED SCREEN PRINT AND COLLAGE WITH HAND COLORING 12 ½” X 12 ½” 2010 SUPPORT Funding for Anchor Graphics is provided in part by contributions from individuals, the Illinois Arts Council-A State Agency, the Cliff Dwellers Arts Foundation, Canson Inc., Google Inc., and the Packaging Corporation of America. If you would like to make a donation to Anchor Graphics please contact us at 312-369-6864 or anchorgraphics@colum.edu. Donations can also be made online through our website at colum.edu/anchorgraphics. 2 ANCHOR GRAPHICS LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR DAVID JONES, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF ANCHOR GRAPHICS. Dear Friends, Welcome to our fall 2010 newsletter. Anchor Graphics’ Artists in Residency program, Publishing, Adult Classes, Workshops, and Internships have been keeping us busy. The range of expression of people coming through the shop has been truly amazing. Writing about each event or program would take up more than my allotted space, so in this issue I’m going to address our Residency program. I am really excited by what I see happening here. From February until August of 2010 we hosted seven residents. As per the residency agreement, we asked each artist to be available to students and to the community, and be willing to talk about their work and process. We held very informal evening events for those presentations. Word is getting out about these events, and with each residency more and more people are showing up. When Chicago-based artist Don Colley was in residence he shared his work with four Columbia classes, and talked about his work methods, history and the career he created for himself. Visitors immersed themselves in his numerous sketchbooks and exceptional draftsmanship. Gordon Brennan and John Brown, our residents from the Edinburgh College of Art, Scotland, showed us how to be open to the benefits of having a loose plan, showing up ready to work, then dealing with the limitations of the working space. They were extremely prolific and created a range of both 2D and 3D objects, prints, and packaging in a flurry of activity. Krista Hoefle, from St. Mary’s College in Indiana, arrived with about 50 cyanotypes that she had created prior to her residency. She started to work silk-screening and collage onto the prints, having an idea of what she wanted, but not sure how the images would look. Recently Ms. Hoefle shared that while she absolutely loved the residency and the opportunities and challenges it presented, the work begun here is still in flux and open to revision. Our residents were willing to take creative risks with their projects and push towards a conclusion that might be vague, letting the work direct them. I see this as a successful process, and a role model for our students. The creative process isn’t necessarily about the work produced but about the journey, the pushing and pulling of ideas, the coming together of individuals to create something whose sum is greater than the parts. Collaboration takes many forms, and our charge is to find and bring in those individuals who will challenge us to try new things, solve complex problems, and perhaps the most difficult, to create compelling works. Anchor Graphics continues to evolve. Yes, we make prints, but it’s more than that; it’s about the art of collaboration, the give and take of ideas, discussions of process, and a lot of trial and error. What comes from this dialogue of ideas is an image. This for now happens to be a multiple printed on paper. I invite you to linger a bit, enjoy the articles in this issue of the Anchor Graphics newsletter, and think about the collaborations in your life. And I invite you to drop in to see what we are up to and take a moment to visit with Chris Flynn and James Iannaccone or me at Anchor Graphics, a part of the Art + Design Department at Columbia College. Sincerely, David Jones Executive Director COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO RECENT 3 EVENTS CRYSTAL WAGNER, MORPHOTIC I, LITHOGRAPH, 22 ½” X 29”, 2010 JOSEPH TRUPIA, GO EASY, SCREEN PRINT, 7” X 10”, 2010, FROM EXCHANGE 7 EXHIBIT I NCI SED , B I TTE N A N D G OU G ED 2 0 1 0 ARTISTS- IN- RESID ENCE SUSAN TA LLMA N LE CTUR E FISH TANK E XHIBIT S Anchor Graphics celebrated its 20th birthday with a retrospective exhibition at the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art. The exhibition featured work created at Anchor through its ArtistIn-Residence and Publishing programs along with work from the Chicago Printmakers Collaborative, which also celebrated its 20th anniversary this year. Incised, Bitten and Gouged: Anchor Graphics and the Chicago Printmakers Collaborative, 20 Years of Printmaking was on view July 30 – September 12, 2010 with work by more than 40 artists in various print media. The end of summer saw the last of our 2010 Artists-In-Residence. Throughout the year seven artists came to the shop to work on new projects and share their wonderfully different working methods and styles of making prints. The 2010 Artists-In-Residence were Don Colley, Zoltan Janvary, Crystal Wagner, Krista Hoefle, Jeanine Coupe Ryding, and the dynamic duo Gordon Brennan & John Brown. Images of the work they created and videos of the lectures they presented can be found on the Anchor Graphics website. In front of a capacity crowd, Susan Tallman, art historian and author of the book The Contemporary Print: from Pre-Pop to Postmodern, discussed the work of John Baldessari. This event was cosponsored by the Museum of Contemporary Photography as part of their exhibition John Baldessari: A Print Retrospective From The Collections Of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation. Recent displays in the Fish Tank exhibition space located next to Anchor Graphics studio included Imirce, a print based installation by Lloyd Patterson Jr. Having moved to and from nine different locations in the last five years, this installation documented his long voyage and his unsatisfied yearning for a place to call home. Also on view was Exchange 7, selections from PrintZero Studios’ print exchange juried by Karla Hackenmiller, Associate Professor and Printmaking Program Chair at Ohio University, Athens. EDITIONS RECENT Anchor Graphics works with artists from around the country to create limited edition prints. Our master printers work in collaboration with the artists to help realize their vision. Both the artists and Anchor Graphics benefit from these partnerships by sharing ideas and splitting editions. Anchor’s prints are available for sale to the public, providing an important source of revenue for Anchor’s programming. Recent editions include work by Don Colley, Onsmith, and Nicholas Sistler. IMAGES (CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT): ONSMITH WORKMAN’S COMP LITHOGRAPH PAPER SIZE: 19 1/4” X 15” IMAGE SIZE: 15 3/4” X 10 3/4” 2010 NICHOLAS SISTLER DOUBLE INDEMNITY PHOTO-POLYMER INTAGLIO PAPER SIZE: 7 ½” X 11” IMAGE SIZE: 4” X 7” 2010 DON COLLEY SENSE LITHOGRAPH 19 3/4” X 14 3/4” 2010 COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO A PARADISE OF THE ORDINARY H E A V E N W O U L D B E full of ordinary things; trees, fresh air, lies and infidelities, chattering animals and sex. What kind of place could it be if there were no ordinary things? Or could we live forever in a limbo of miracles and the constantly renewed fires of the super-real? We are fascinated by the ordinary and in just about anything in this world and the imagined next. You can’t turn around without tripping over the ordinary and its omnipresent power to be more than artifice. The problem with painting is not just that it celebrates such artifice, but that it has no ambition. A single self-conscious brush stroke, pulled against the grain of the canvas, cannot fail to disappoint. Magnify that number into the millions and you may resuscitate the medium, but who has the time? The painting might be dull, but the pain in the wrist is delightful. We have to have faith in something. Rauschenberg knew that if he opened his window the world would rush in. Of course this is more beautiful than superstition. Of course it’s more tangible than god. We don’t mind if god exists because we know the folly of the teleological: we object to heaven. An algorithm can provide a fascinating and absurd selection. It looks like randomness. It was Cage’s genius to recognize this power. To him we owe what we have become. We know this upsets pockets of a previous generation, as well as those younger that cradle dust, but the burden of relevance fails to weigh on the shoulders of fools and the forgotten. We are passing the age where sex is rewarding and we look past ourselves in mirrors. Man has created god in his own image and there’s no morning-after pill for that. Lacking the appropriate contempt for ourselves, we have invented redemption and justice. It’s time to throw the baby out too. It’s no use just wanting to be ordinary. Anchor Graphics is teaming up with Industry of the Ordinary to produce a series of four-color photolithographs. Industry of the Ordinary is a collaborative team composed of Adam Brooks and Mathew Wilson. They state that: “Through sculpture, text, photography, video and performance, Industry of the Ordinary are dedicated to an exploration and celebration of the customary, the everyday, and the usual. Their emphasis is on challenging pejorative notions of the ordinary and, in doing so, moving beyond the quotidian.” The source material for this series of prints is the result of image searches on Google through which the word ‘Ordinary’ is combined with a particular language. Pairings are produced that reflect important historical tensions or other charged relationships between speakers of these languages. The artists take randomly selected images that result from these searches and zoom in on a specific section. This close up is then combined with the close up from the search of another language, creating a diptych that will be printed using photolithography plates. The work will be framed in shadow boxes with the word “ordinary” in the correlating languages sandblasted on to the glass. Stay tuned for more on this project in future newsletters. More information on Industry of the Ordinary can be found on their website at industryoftheordinary.com. 5 6 ANCHOR GRAPHICS EL CORAZÓN DE LA OSCURIDAD F O L L O W I N G T H E A R R I V A L of Christopher Columbus, the Spanish empire would expand across much of the western hemisphere, spreading through the Caribbean Islands and along the west coasts of North and South America. When the Spanish arrived in Alaska, only a few decades behind the Russians, their territory would reach from the rim of the Arctic to the edge of the Antarctic. In Mexico, the campaign against the Aztecs would become one of the first great successes of the Spanish colonization of the mainland. The Aztecs described the arrival of the Spanish as proceeded by seven omens including the destruction of temples by lightning, boiling lakes, and streaks of fire across the oceans. They would arrive from the Gulf of Mexico and land in the kingdom of Motecuhzoma, also spelled Montezuma. The Spanish set sail from Cuba in 1519 under the leadership of the mutinous Hernan Cortés. Cortés had been instructed to initiate trade with the indigenous coastal tribes. However there was a clause in his orders that enabled him to take emergency measures without prior authorization if it would further the interests of the Spanish crown. He eagerly assembled a fleet of eleven ships and hundreds of well-armed men intent on conquering the mainland. The Cuban governor had hoped to keep the glory of such an expedition for himself and revoked Cortés’ commission. Cortés hurriedly set sail anyway. Faced with imprisonment or death for defying the governor, Cortés’ only course of action was to succeed at his enterprise and hope it would redeem him in the eyes of the Spanish king. Once they reached shore Cortés scuttled all but one of his ships to prevent any of his men from trying to return to Cuba. The remaining boat was used to carry plundered gold that would buy the king’s forgiveness. Cortés allied himself with the Tlaxcalans, who after nearly a century of conflict with the Aztecs knew it was only a matter of time before their fellow Mesoamericans would conquer them once and for all. With their aid, Cortés marched on Cholula, the most sacred city in the Aztec empire. Because it was a holy site, it was guarded by only a small army that relied more on deities than weapons for protection. The people were massacred and the city was burned. The tale of Cholula had a chilling effect thoughout the Aztec empire, causing other cities to submit to Cortés’ demands rather than risk the same fate. Three months later Cortés arrived at the outskirts of Tenochtitlan. Set on an island in Lake Texcoco, Tenochtitlan was the center of the Aztec empire and one of the largest cities in the world, rivaling Constantinople in population. It is said that Motecuhzoma warmly welcomed Cortés and his army. As reciprocity for his hospitality Motecuhzoma was taken prisoner. Soon after Cortés would receive news that another Spanish expedition from Cuba had landed on the coast with orders to hijack his conquest and bring him to trial. Cortés mobilized against the new invaders. Taking a small force, he surprised and defeated his fellow Spaniards, subsequently recruiting many to his side by telling them the Aztec capital was a city made of gold. Returning to Tenochtitlan, Cortés found that the locals had risen up against the men he left behind. He ordered Motecuhzoma to speak to his people and persuade them to let the Spanish leave peacefully. Angered by his submissiveness, the Aztecs would stone Motecuhzoma, inflicting fatal injuries. The Spanish and their allies were forced to flee, suffering heavy casualties in their retreat. DON COLLEY LOTERÍA LITHOGRAPH 15” X 20” 2010 COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO 7 8 ANCHOR GRAPHICS IMAGES FROM MANO/MUNDO/CORAZÓN: ARTISTS INTERPRET LA LOTERÍA EXHIBIT (CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT): CHRIS FLYNN EL COTORRO DRAWING, DIGITAL PRINT, AND COLLAGE 9 ½” X 12 ½” 2010 Many of Cortés’ soldiers were captured for sacrifice to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war. Human sacrifice was central to many Mesoamerican cultures. The Aztecs believed that the gods had sacrificed themselves so that mankind could live. Everything in the cosmos sprang from their blood and severed body parts. The Aztecs sought to repay their debt to the gods through on-going sacrifices, which would help sustain the universe. Human sacrifice was the highest form of offering and frequently practiced by extracting the victim’s heart. The Aztecs saw the heart as a fragment of the Sun’s heat trapped within the body. Heart-extraction was viewed as a means of liberating the fragment and reuniting it with the Sun. A soldier would be placed on a sacrificial stone while a priest would cut through his abdomen with an obsidian blade. The heart would be torn out still beating, held towards the sky, and then cremated. The rest of the body would be given to the warrior who had initially taken it prisoner. It would be cut into pieces that were used for ritual cannibalism or sent to important community members as tribute. Cortés and his remaining men regrouped in Tlaxcala. When fully healed they would once again prove to be a formidable fighting force. One by one they conquered all of the cities of the Aztec empire before laying siege to Tenochtitlan. After eight months of cannon fire, starvation, and smallpox the city was at last surrendered. The smoldering ruins would provide the foundations for what would become Mexico City. By the 1700s the Spanish were well rooted in the region. Spanish immigrants to the New World would bring much of their home culture with them, including a game called lotería. It is a game of chance that came to be used as a way to encourage the natives to acquire the Spanish language, European customs, and the Catholic religion. Despite its foreign origin lotería has become a deeply entrenched cultural force in modern day Mexico, frequently played at festivals and celebrations of all kinds. Similar to Bingo, lotería uses a deck of 54 cards, each with an image, name, and number. Players have at least one tabla with randomly selected pictures from the deck arranged in a 4 x 4 grid. The cantor selects a card from the deck and announces it to the players, often using a riddle or humorous poem. Such phrases, like the pictures on the cards, have numerous regional varia- HUGH MERRILL LA SANDIA 9 ½” X 12 ½” 2010 tions and often play with the associations of the image. Thus, the rooster can be announced as “I sing for St Peter”, the sun as a “coat for the poor”, and the devil becomes the “sweet Virgin Mary”. The players, with a matching pictogram on their board, mark it with a chip, small rock, or pinto bean. The first player with four images marked in a specified pattern is the winner. As is likely to happen with games of chance, lotería became a form of gambling for Mexico’s wealthier upper classes. Players competed for a pot of money accumulated by charging a fee for each tabla and by covering the images on the game cards with extra bets. In the practice of gambling a player hopes to be lucky and needs to have faith. This often leads to superstitions, which can then be projected onto the cards themselves. Accordingly it is believed that lotería decks can be used for fortune telling and divination much like tarot cards. Ripe with cultural heritage and symbolism the cards’ iconographic images can easily be made to correspond to values, attributes, or relationships found in man, nature, or society. As cards are pulled these attributes and relationships begin to reveal one’s destiny. The same symbolism that endows lotería cards with mystic abilities also makes them incredibly attractive to artists. Several artists who have made work based on the game have been included in the exhibition “Mano/Mundo/Corazón: Artists Interpret La Lotería” at the Center for Book and Paper Arts through December 10, 2010. The exhibition features a culturally and geographically diverse group working in film, photography, installation and painting. Newly commissioned works on paper based on individual cards plus a series of lotería inspired prints from Aardvark Letterpress are also on display. In conjunction with the exhibit Anchor Graphics set to work with Chicago artist Don Colley to create a lithograph that will act as a frontispiece. The lithograph derives its imagery from the show’s title depicting a hand, globe and heart. In the background is a representation of a paper cutout know as papel picado. This traditional folk art is found throughout Mexico and like lotería is often present during holidays and celebration in the form of brightly colored strings of cut tissue paper hanging across streets and adorning buildings. Papel picado is a synthesis of Asian, European, and Pre-Columbian artistic traditions. The Moors, who occupied Spain begin- FRED STONEHOUSE LA CALAVERA PAINTING ON PAPER 9 ½” X 12 ½” 2010 JAVIER CARMONA LA MANO 9 ½” X 12 ½” 2010 ning in the 8th century, introduced the art of paper cutting to the Iberian Peninsula through trade routes with China. In the centuries that followed it would spread to the rest of Europe, becoming known as scherenschnitte in Germany, wycinanki in Poland, and silhouettes in France. The Spanish brought the art form to Mexico where it combined with an indigenous tradition of paper cutting. The Aztecs produced a type of paper, known today as amate, by mashing pulp made from the bark of fig and mulberry trees between rocks. Once dry the paper was cut with knives to form ceremonial images of gods and goddesses. Both the Old World and New World traditions fused to form papel picado, which continues to evolve as a living folk art. The hand, globe, and heart found on Don Colley’s print adopt the color schemes and dot patterns of mid 20th century Mexican advertising. Following the Mexican Revolution, the social engineers of the newly formed government were attempting to forge a national identity from a fragmented and ethnically diverse Mexico. At the same time increasing numbers of the rural population were heading towards the cities, forming a new consumer class. Companies in both Mexico and the U.S. were trying to sell them items such as cigarettes, liquor, and soda pop by reproducing paintings of the products, often accompanied by beautiful women and Aztec kings. Such advertising art reflected the changing image Mexicans had of themselves. Increasingly patriotic and filled with cultural pride, they embraced a nostalgic sense of national identity. Reclaiming and empowering a pre-Spanish heritage, they depicted the creation of Mexico as an idyllic time, with powerful warriors wearing feathered headdresses and rich jewelry, standing guard over a vibrant land with beautiful princesses at their feet. The youthful bodies of these figures and the bounty that surrounded them portrayed Mexico as a strong country ready to take its place in the world. Don Colley shows regularly in galleries across the country and has been exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Austin Museum of Art. More information and images are available on his website at buttnekkiddoodles.com. The print he created for the Mano/Mundo/Corazón exhibit is available for sale through Anchor Graphics. COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO SLOW RELEASE G O R D O N B R E N N A N & J O H N B R O W N were S D : When I look at the box set with the toys, the artists-in-residence at Anchor Graphics in August 2010. At the end of their residency they were interviewed by Sibel Duzenli, a summer intern and exchange student from Emily Carr University of Art and Design. The following are excerpts from their conversation. postcards, the tickets and you as international artists, it makes me think of travel and of travel as a leisure activity. Do you think that travel has brought something to this work? S I B E L D U Z E N L I : You are working collabora- tively on a project based on the Chicago World’s Fair of? J O H N B R O W N : 1933–1934. Loosely based on. SD: How did that come about? Why was that the theme? G O R D O N B R E N N A N : We came to Chicago two years ago, had two weeks to make a show and present it. We used the idea or the spirit of the ’33–’34 World’s Fair, a temporary event that took a long time to make and was only on for a short period of time. The two weeks were spent primarily with a little bit of research and lots of production. The show opened for one day and closed. The following year we came back and, like the World’s Fair where the ephemera and the memorabilia lasted longer than the actual event, we made another show based on the memorabilia and the ephemera from the first show. So that was the two years prior to this residency. What we are trying to do now is condense all of these elements into one box set of ephemera. J B : I think you’re right. For all the projects we’ve done we haven’t brought any stuff with us. It’s literally underpants and socks. Everything is bought here or the imagery is here. It’s like the idea of the immigrant coming just with a suitcase. G B : It’s also being away from our own environment. You remove yourself from the way you are and see things differently. That’s an important aspect of it. The box is like the Duchamp Valise, which is a summing up. Component parts or previous bodies of work come together. It’s not an exact reproduction of these things but it catches the spirit of these previous works. J B : I think what you grow up playing with creates your aesthetic. It’s built in. You can’t get rid of it. When you look at boxed sets of toys there is an aesthetic there, a look or feeling. It’s the mixture of the flat printed thing and the real object, the fact that you can lift things out and move them around. It’s not one static image. It’s a whole world that’s got possibilities of imagination. G B : It’s like the idea of a collection. It’s not just one thing. It’s the component parts put together and the possibilities within these component GORDON BRENNAN POSTCARD FROM BOX-A-RAMA RELIEF PRINT, 6” X 9” 2010 11 12 ANCHOR GRAPHICS parts. It’s not meant to be an accurate representation of one particular thing. We make things that we can’t actually find. That’s why we make them. That’s why we make art, because it doesn’t exist. The thing you want doesn’t exist so you’ve got to try and make it. the research you did and there were some visits. version of it. We have put a filtering process between the source and the things for the World’s Fair, those loads of ephemera and souvenirs. The thing was on for two years and the stuff that was given away has lasted a hell of a lot longer than any of the events. The idea that an object will spark off a memory, an association, so it again becomes about experience and not just information, that’s the best bit. J B : To Uncle Fun? [Uncle Fun is a toy store in S D : Even inside a small seemingly insignificant Chicago] object? S D : Yes. Tell us about the research you did for G B : It’s the detritus. It’s the small things. It’s the things in between the big things that are important and that’s what you remember, not necessarily the big events. You remember these little things that spark off something for you. S D : I remember talking with you a little bit about this project. G B : Obviously there are different kinds of research. There’s a research which is about gathering information and there’s a research which is about experience. It’s not necessarily the kind of serious research at a desk where you look things up. It’s about coming across something and bringing your own sensibilities to it. Uncle Fun was all the crap in the world in one place. It’s almost too good, so we’ve tried to make our own S D : It seems like you were working towards a certain aesthetic of the disposable object, the kind of tourist ephemeral stuff. J B : And trying to make people think a little bit about packaging, or the packaging vs. the ob- COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO 13 JOHN BROWN NEW WORLD PHOTO PLATE LITHOGRAPH IMAGE SIZE: 9” X 6” PAPER SIZE: 13” X 10 ¼” 2010 ject within. But in terms of how we worked on it, it has been a case of problem solving. Finding the box, printing the box, finding out how things work and fit within the box. It almost feels like a sketch. It’s like we have been at the forefront of trying to invent with this thing. It’s not a case of making something to a plan. It’s being made as we are thinking about it. Yesterday we saw some blueprints from the World’s Fair so we’re going to make a postcard that’s a photocopy of a sketchbook page that’s a blue print for this project. So things are coming in. As our trip builds the box builds as well. J B : It’s perfect for this. Exactly what we wanted to do. We’re not pure printmakers by any means. So we’ve learned a heck of a lot. It got us thinking on our feet. G B : It’s also using the processes, using the language of printmaking. If you are making a painting it has to be about the image obviously but it also has to be about the act of making a painting. When you’re making a print it has to be about making a print as much as it is about the image. S D : I think you really took advantage of print it. We’ve got two or three lives from this body of work. There is the potential to do more with these things. It is ongoing. The end of this process is the beginning of the next one. I don’t know what the next one will be yet but I feel there is something to come. J B : I was thinking last night and looking through my sketchbooks from the first week. It’s amazing the first things you see or think about are what comes back into it. It’s first thought, best thought. When you arrive somewhere new your eyeballs are bouncing around. That’s usually what you use visually. There is something about that kind of freshness. We can only do this here with these people and it’s not something we can go away and do again in Edinburgh. It’s something now. collaboratively removes you from your own way of working. You have to think collectively rather than independently. It’s removing your ego to try and produce this thing that has the sensibilities of both of us and not just a little bit of mine and a little bit of John’s. methods when you were working on labels and trying to get that aesthetic of packaging. Talk a little bit about the process you went through. It wasn’t simply I’m going to make a print and it’s going to look like this. There was a translation of original drawing into another kind of information. S D : When you work together on a project and J B : Four-color plate litho, the way it separates the then go back to your studio, does it make it easier to work as an individual? S D : It seems like a perfect type of collaborative dot, makes it more hazy. You can’t reproduce it through painting. I can’t do that with painting. G B : There’s also the situation where working project having all of these offshoots that all come together. Do you think that working on several smaller things in a collaborative way is easier than working as an individual on the same type of thing? J B : It’s double the brainpower. G B : When you are working collaboratively you ask so many more questions because you are partly responsible for somebody else’s work. I suppose it also relates back to when we are teaching. We still teach in a place where the studio culture is important and working with other people is important. Even if you are not working collaboratively you are working next door to somebody and that passing comment over a cup of coffee can make a big difference. S D : In printmaking studios there is always collaboration. Do find that being in this particular type of environment propelled you forward? Was printmaking a good process for this project? G B : It’s about trying to remain true to the process as well as the idea. S D : Do you think that the experience in the studio affected the way you think about print media in the fine art world? J B : I never thought in the end there would be bagged items. As a fine art installation that might look quite interesting with a hundred of those on a wall. Gordon had his pieces up in the studio last night and it looked great just as an installation. So it’s got more than one life. G B : I think that’s always something we try to do. When you have an exhibition it’s an event like the World’s Fair. When you’re making an exhibition you struggle for a year in the studio. You put the work on the wall. It’s up for a few weeks and it goes. So what’s the aftermath? Is there a slow release from that, an extra life? With the idea of ephemera you can build that longevity into GB: I think it gives you confidence. Thinking of some of the other things we have done, I certainly made work I never would have made and it gave me a freedom when I went back to doing stuff on my own. I had this body of work behind me, a momentum behind me that I could then go back and plunder and build on. You need that catalyst sometimes. Audio of the complete interview can be heard on our website, colum.edu/anchorgraphics, along with more images of the work created, and video of a lecture presented by Gordon and John. ANCHOR GRAPHICS A PROGRAM OF THE ART + DESIGN DEPARTMENT AT COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO UPCOMING PROGRAMS 623 S. Wabash Ave., Room 201 Chicago, IL 60605 312 369 6864 anchorgraphics@colum.edu colum.edu/anchorgraphics WHEN AFTER COMES BEFORE JANUARY 13 – FEBRUARY 12, 2011 at the Averill and Bernard Leviton A + D Gallery 619 South Wabash Avenue, Chicago Opening Reception: January 27, 2011, 5–8 p.m. Artists Lectures: January 27, 2011, 6:30 p.m. According to art historian Wu Hung any artifact of the past has to exist in the present. In the work of Phillip Chen and Thomas Vu the opposite is also true. Their artifacts of the present exist in the past. Their prints collapse time creating an incongruous space where linear knowledge is replaced by a state of simultaneity. Drawing from personal experiences, memories and written history their work incorporates both long departed and surviving traditions, beliefs, objects and landscapes, positioning all firmly within a contemporary context. The push and pull of yesterday and today is encompassed in the very materiality of the work, constructed using computer-controlled technologies such as laser cutters combined with old-school hand printmaking. Their work is at once a documentation and a schematic diagram of the present as seen through the past and the past as seen through the present. As such their work takes on a cosmological appearance. With his Theory of Relativity, Albert Einstein proved that the passage of time is dependant on one’s frame of reference and this is certainly the case with the work of Phillip Chen and Thomas Vu. ANCHOR GRAPHICS AT SGCI CONFERENCE MARCH 16 – 19, 2011 Anchor Graphics staff will be at the newly renamed Southern Graphics Council International Conference in St. Louis presenting demos, a panel discussion, and exhibiting work at the publishers fair. Anchor’s master printer Chris Flynn will be demonstrating photopolymer intaglio plates, administrative assistant James Iannaccone will chair a panel on how to make a business out of screen printing posters for rock bands, and director David Jones will be displaying some of our latest creations at our publishers table.