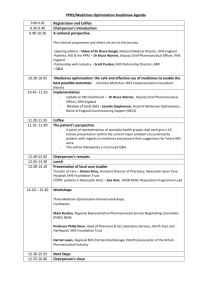

Pharmaceutical Industry Competitiveness Task Force Final Report – March 2001 Pharmaceutical Industr

advertisement