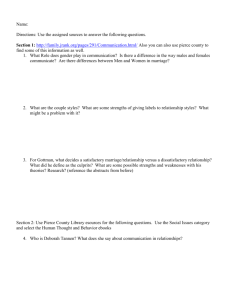

Ψ Psychology Student Research Journal

advertisement