Ensuring Success for Returning Veterans

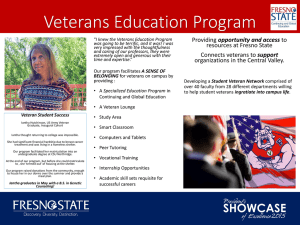

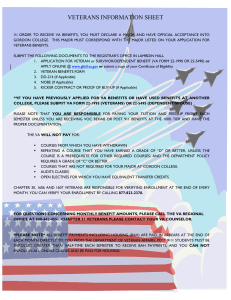

advertisement