1 Back with the Old Brigade C H A P T E R

advertisement

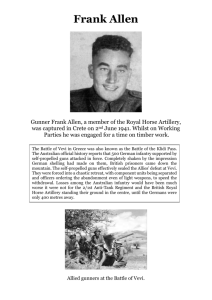

CHAPTER Back with the Old Brigade 1 Armistice Day—Mailly-le-Camp—Haussimont—General Chamberlaine—Naval Guns—In Front of the Front—Prisoners of War—Étain—Metz—Marshal Pétain. Sunday, November 10, 1918 It had been finally decided that pending my promotion to major general and command of an infantry division, I should go up to the front and take over the old Railway Artillery Brigade with which I had come to France. This brigade had been reorganized once or twice, split up to form new organizations, and was now known as the 30th Railway Artillery Brigade.1 Harbord was certain that the appointment as major general would come along any day and advised me to study the organization and tactics of the infantry division at every possible opportunity.2 He said he had found himself painfully ignorant upon this subject when he took command of the Marine brigade at Château Thierry.3 He presented me with some writing paper stamped with major general’s stars, and after a sad adieu to all my old associates at Barracks 66 and at Beaulieu,* I left for Mailly at 2:30 p.m. and arrived in Paris at 7:30. I went to the Y.M.C.A. hotel—Hôtel Richmond—for the night.4 Monday—November 11th, 1918 L’Armistice Est Signé I suppose that if a man were asked where he was on Armistice night, he might derive some concealed pleasure by replying nonchalantly, “In Paris,” adding, “At the Folies Bergères.” That’s where I happened to be.5 General Pershing says that many foolish things were done in Paris on Armistice night, by persons whose ordinary conduct was marked by dignity *Our château at Tours. 16 Caissons Go Rolling Along and composure. I can vouch for this. But among the things they did not do in Paris that night was to blow whistles and ring bells, unless it were [sic] chiming the cathedral bells. Parisians do not find amusement in disagreeable noises—in screeches or clangs, harsh rattles, or even in yells. Nor do they get anything out of synthetic fun—the kind of fun that bores you, but (in your imagination) enlivens other people. A Frenchman’s idea of pleasure is personal, not collective. The people of Paris went out on Armistice night to have a good time themselves, not simply to watch other people make fools of themselves.6 At the Folies Bergères a good time was had by all. The foyer of this famous resort is a large hall, filled with tables, where they serve wines and light refreshment. There were ladies present—Ladies of the Stage, Ladies of the Audience, and Ladies of the Street. Passing one of the tables, an American general officer was invited to sit down. Said a young lady in a pleading voice, “Asseyez-vous, Mon Lieutenant.” “Shush,” said the captain with her, “That’s not a lieutenant! That’s a general.” “Oh, Mon Dieu,” said the young lady, “C’est un Général.” Throwing her arms around his neck, raising both feet off the floor, and trying to kiss him, she said, “Pardon! Pardon! Mon Général! But won’t you sit down anyway?” The general was very much embarrassed. Generals had been sent home for less (so it was said), and whatever may have been his private inclination, his public reaction was in the nature of a rebuff. November 13th—November 16th In Paris I met General William Chamberlaine, the commander of all the American railway artillery, who had come to see a 14-inch naval gun at Versailles enroute to the front. He was my new boss, and he directed me to remain over a day and return to Mailly with him.7 What a different aspect Mailly presented from what I saw in it a year ago. All of the novelty and romance had worn off. I had seen many French camps and barracks, both at the front and at the rear, and Mailly struck me now as a dull headquarters, full of drudgery, paper work, and red tape. There were none of my old French friends. The Germans had been very near to capturing it. It had often been the object of air raids. The French had moved away everything not absolutely essential. General Chamberlaine General Chamberlaine was an old friend of mine. We had served as captains together in the Coast Artillery in the old days at Fort Monroe and had come to France together in the 1st Expeditionary Brigade, he as colonel of the Sixth Regiment and I as colonel of the Seventh. Chamberlaine was an extremely able officer and, as commander of all the American railroad artillery, should have been at least a major general. In the British service, he would have been Back with the Old Brigade 17 a lieutenant general, but as it was, he was only a brigadier, while under him, in command of only five guns, was a navy officer of the next higher grade. The American Army seems to be always trailing the Navy, the Marines, and all the foreign armies in the matter of rank because it can never make up its mind whom to promote, so lets the whole thing go by default. Chamberlaine gave me a dinner. As was usual in army messes in France, he had soldiers in uniform waiting on the table, but this was the first time I had seen them wait “in a military manner.” They marched about in truly astonishing fashion, executing movements in unison, and serving the guests in the order of their rank. Each new course was brought in with as much ceremony as if we were changing the guard. After dinner Chamberlaine took me out on the lawn and exhibited a trained goose and four ducks. He showed some food. The goose came forward with his neck stretched and hissing. The ducks flapped their wings and quacked. Upon being shown more food, they repeated the performance. “What do you think of them?” he said. “Pretty good,” said I. “Do you think they are intelligent?” “Why yes, quite so.” “I find them useful.” “Useful?” “Yes. That is my general staff. The goose is chief of staff, and the ducks are the G’s.”*8 Notwithstanding General Chamberlaine’s little jibe, he was a great believer in the general staff, and later upon his return to the United States, set up a very rigid system of G’s at Fort Monroe. November 17th–November 18th From Mailly I went to St. André, headquarters of the 30th Brigade at the front. This little village of three or four houses was a few miles back of Verdun9 and quite near Souilly, headquarters of the First Army.10 I was directed to withdraw the railway artillery from their positions in the line and to send them back to Haussimont.11 This having been accomplished, I moved my own headquarters back to the same place. I found that the brigade consisted of the 42d, 43d, 52d, and 53d regiments, but these regiments had never been together, and the records at brigade headquarters did not even show who was in command of them. They had been formed out of the old 7th and 8th regiments, but there was not an officer of the old organization still with them.12 *Assistants 18 Caissons Go Rolling Along General Pershing talking to British W.A.A.C. at Tours, July 29, 1918, Generals Harbord, Hagood, Kernan, and McAndrew, in the background. There were a number of the old soldiers still left, and the night I arrived some of them serenaded me and made a little speech saying they were glad to have me back.13 The camp at Haussimont had been located in an open field at the intersection of two important highways constantly filled with traffic.14 When it rained, the mud was ankle deep, and in dry weather, it was correspondingly dusty. Everything was dirty, and the quarters set aside for me were filthy. I started at once to clean them up, had the walls papered, a bath installed, and Back with the Old Brigade 19 made arrangements to improve the mess. I had started this camp by building a battalion barracks. Now it had grown to accommodate six regiments. There were many railroad tracks, and all the railroad artillery used by the Americans at the front was being collected there. Navy Guns I was struck with the 14" Naval Guns. Admiral Charles P. Plunkett15 told me that in February 1918 the Navy had decided to replace the 14" guns by 16" guns on their battle cruisers.16 They had the Baldwin Locomotive Company construct railroad mounts for these guns and offered them to the War Department. There was some opposition at first, but General Peyton C. March, the Chief of Staff, accepted the whole thing including the Navy crews.17 Thus the Navy started out in February, got to the front, and participated in the fight, while the Army artillery drifted around for two years without ever getting into action except with guns and ammunition borrowed from the French. The Navy gun was far from perfect, but it was better than nothing at all.18 In Front of the Front On November 15th, I set out with Roger Wurtz,19 my French aide to look over the positions occupied by the railway artillery during the last offensive, and also to report on the effect our fire had upon the Germans. We went first to the northwest of Verdun to Charny and Cumières, and passed through the villages of Marre, Thierville, and Chattancourt.20 These towns had been alternately in German and French territory and had seen some of the heaviest fighting of the war. The devastation was terrible, and of the town of Marre, there was nothing standing—not even a piece of wall two feet high. The next day we passed through Verdun and up to the northeast, through the old German positions. For miles in every direction, the ground was pitted with shell holes and looked like the surface of the moon does through a telescope. Houses were down in ruins, and there was no sight of human habitation except a few dugouts. The city of Verdun was pretty badly shot up. Every house in town seemed to have been hit, but it was still inhabited and did not look much worse than Soissons when I was there in October 1917. The city was protected by the old citadel, which was still intact. We looked over the German lines beyond Verdun and went into some of the dugouts but didn’t find any damage that we could identify as our own. Prisoners of War The next day we went to Conflans to see what damage we had done in that direction. We passed through Étain where we met a great many returning war prisoners.21 There was a sign, “Food for Prisoners of War only,” and an 20 Caissons Go Rolling Along American sergeant told us that two thousand had been fed during the preceding day. They were a pitiful and dejected lot. No hobo on the vaudeville stage could have looked more grotesque. Ragged and dirty, with hair and beard matted, they had a vacant stare that suggested the absence of human instinct.22 I pictured the scene when such loathsome creatures appeared at their homes where they had been waited for so long. It was like seeing the body of a friend who had been drowned.* Behind the German Lines Arriving at Conflans, we found flags flying and signs of welcome to the Allies. This was rather hard, because we had fired on this town, but we did not seem to have hurt it very much. Our target had been the railway yards. Several trains had been hit by 400 mm (12") shells, the cars were knocked about, and some track upturned.23 American engineer troops were at work repairing the damage. American soldiers were running a captured German engine, shifting material about the yard. We went back through Étain to a high hill about fourteen kilometers distant, and three kilometers inside the German lines. This had been an important observation point and had been heavily shelled by both the Americans and by [the] French. We saw everywhere, evidence of good organization, substantial camouflage, and great dependence upon light railroads.24 The German dugouts and trenches seemed much better than any we had seen on our own side. They used a good deal of concrete and a kind of adobe mud. There was quite an ornamental waiting station in one little shot-up village, constructed of cement for the light railways. The tile roofs of Étain had been removed and used for shelters in ammunition dumps. I noticed also that all the field magazines had regular flooring of tongued and grooved material.25 On the battle field between Étain und Conflans, we picked up some large brass shells to bring home as souvenirs. Some of them were big enough to be used for umbrella stands.26 November 19th Visit to Metz At the suggestion of Roger Wurtz, I decided to go to Metz, to see Marshal Pétain march in at the head of his troops.27 We crossed the Meuse at Dieuesur-Meuse and went as far as Haudiomont where we struck the main VerdunMetz highway. The town had been destroyed. Few people had been there since the retreat of the Germans, and the roads were well nigh impassable. We got as far as Manheulles, which was No Man’s Land in July 1918. We *See p. [91]. Back with the Old Brigade 21 met some French officers who said it was impossible to go further. The destruction and desolation were terrible. We turned back and, paralleling the old line five kilometers to the west, reached Vigneulles without difficulty. Running through the middle of the forest between Les Eparges and Vigneulles, there was a desert zone about half [a] mile wide, the worst thing that I had seen up to this time. The trees had been shot down, uprooted, and destroyed. Every inch of the ground had been turned time and time again by the explosion of shells. Through it all was a mass of wire like an immense briar patch, tangled higher than a man’s head, half a mile in width, and [extending] as far as the eye could see in both directions.28 When we had gone beyond this, the road got fine again, and we passed well organized German camps with many huts in the open woods and some nice cottages for officers. There was a peaceful German graveyard, some graves with monuments and most of them with substantial stones. It was as well marked as a cemetery at home. Vigneulles was nothing but a place where something had been. We passed through one more town, Chambley, and then crossed into German territory— Alsace—at Gorze. This was the first inhabited town we saw. It was decorated with French and American flags. The people flocked around us, and I took some pictures of Alsatian girls. We had lunch at Ars. They had nothing in the restaurant but German bread—heavy, soggy stuff that looked like ginger cake, but had no taste. We had taken our own lunch, but they offered some beer. Marshal Pétain Metz had been carefully prepared to receive Marshal Pétain.29 There was a conspicuous lack of enthusiasm, though an old woman said to Wurtz, “We have waited for you for fifty years.” Many French and American flags were displayed, some Belgian and two British. There were young girls in Alsatian costumes, but the crowds were not spontaneous. I have never seen such soldiers as the French that marched through Metz that day. They put it over any American or British soldiers I had ever seen. Of course, they were especially selected and were cleaned up for the occasion, but they made a wonderful showing. Every man had his chest just covered with decorations. I was sorry we had not captured Metz, which according to some authorities we might easily have done after the Battle of St. Mihiel, but I was glad we had not shot it up.30 Some of the people of Metz had amused themselves by upsetting an equestrian statue of the Kaiser, otherwise the city changed over from German to French without incident.31