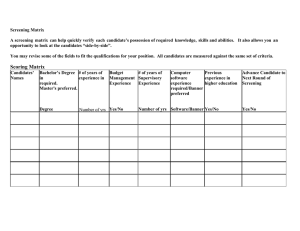

Building Credibility into Performance Assessment and Accountability Systems for Teacher Preparation Programs:

advertisement