The Gnu 1 A Literary Journal

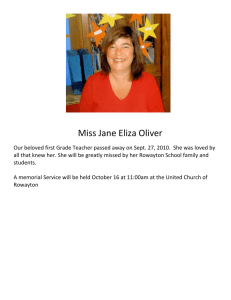

advertisement