Document 14297012

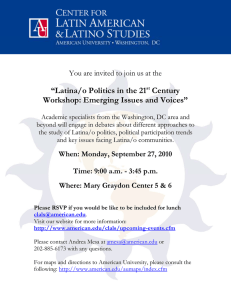

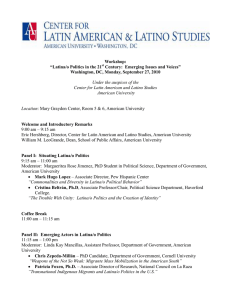

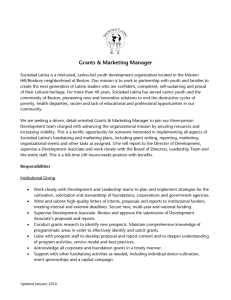

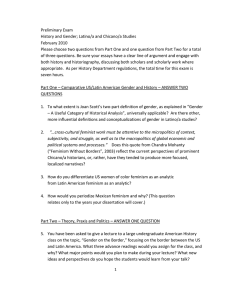

advertisement