M H C —P

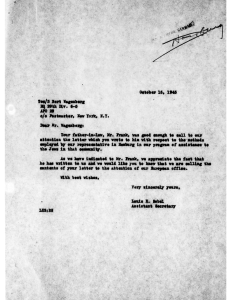

advertisement