Revolution Building the U.S. (1754-1800), part1: Period3, Ch6-8 Study Guide

advertisement

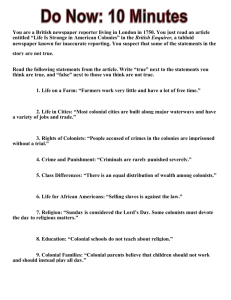

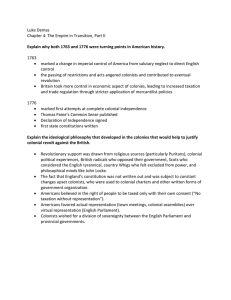

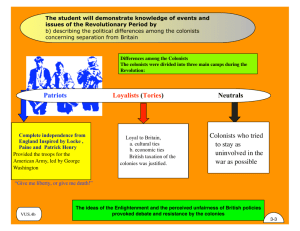

Period3, Ch6-8 Study Guide NAME: ____________________________ Building the U.S. (1754-1800), part1: Revolution (Ch. 6-8) ...is about exploring roots of colonial discontent with British rule and the steps toward American independence. Objectives: 1. Compare French colonization of North America with British colonization. 2. Analyze the causes and effects of the French & Indian War. 3. Analyze the historical factors that caused America to move toward independence and the justifications for revolution. 4. Analyze the outcomes and impacts of the American Revolution. 5. Analyze how broader global developments (ideas, migrations, politics) impacted the American colonies between 1754 and 1783. 6. Evaluate the significance of colonies’ regional differences in the period 1754 and 1783. (Political, Economic, Social, Geographic) 7. Analyze the roles and experiences of Native Americans and African slaves between 1754 and 1783. 8. Analyze the significance of trade and labor systems in the colonial American economy. Key Concepts: Explain the definition, role, and significance of… Chapter 6 Edict of Nantes Huguenots Louis XIV New France Quebec Seven Years’ War French & Indian War Albany Plan of Union George Washington Pontiac’s Rebellion Proclamation of 1763 Paxton Boys Chapter 7 Republicanism Mercantilism George III George Grenville Navigations Laws Sugar Act Quartering Act Currency Act Stamp Act Virtual representation No taxation w/o representation Non-importation Sons of Liberty Declaratory Act Townshend Acts Letters from a Farmer in PA Boston Massacre Committees of Correspondance Boston Tea Party Intolerable Acts First Continental Congress Patrick Henry Minutemen Lexington and Concord Mercy Otis Warren Chapter 8 Second Continental Congress Continental Army Olive Branch Petition Common Sense Thomas Paine Republicanism Thomas Jefferson Declaration of Independence Loyalists Patriots Franco-American Alliance Iroquois Confederacy Ben Franklin 1783 Treaty of Paris Unit Summary British imperial attempts to reassert control over its colonies during the early to mid-1700s and the colonial reaction to these attempts produced an increasing desire for independence. As part of their worldwide rivalry, Great Britain and France engaged in a great struggle for colonial control of North America, culminating in the British victory in the Seven Years War (French and Indian War) that drove France from the continent. Before the Seven Years' War, Britain and its American colonies had already been facing some tensions as can be seen in sporadic British efforts to enforce trade laws. During the Seven Years' War, the relationship between British military regulars and colonial militias added to the tensions. The French defeat in the Seven Years' War created conditions for a growing conflict between Britain and its American colonies. The lack of a threatening European colonial power in North America gave the American colonists a sense of independence that clashed with new British imperial demands such as stationing soldiers in the colonies and the Proclamation of 1763. Migration within North America, cooperative interaction, and competition for resources raised questions about boundaries and policies. English population growth and expansion into the interior disrupted existing French–Indian fur trade networks. Various tribes attempted to forge advantageous political alliances with one another and with European powers to protect their interests, limit migration of white settlers, and maintain their tribal lands. As a result of Britain’s victory over France in the imperial struggle for North America, white–Indian conflicts continued to erupt as native groups sought both to continue trading with Europeans and to resist the encroachment of British colonists on traditional tribal lands. The French withdrawal from North America and the subsequent attempt of various native groups to reassert their power over the interior of the continent resulted in new white–Indian conflicts along the western borders of British colonial settlement. During and after the imperial struggles of the mid-18th century, new pressures began to unite the British colonies against perceived and real constraints on their economic activities and political rights, sparking a colonial independence movement and war with Britain. Tension between the colonies and Britain centered around the issues of mercantilism and its implementation. The British Empire attempted to more strictly enforce laws aimed at maintaining a system of mercantilism while colonists objected to this change from the earlier "salutary neglect." Great Britain’s massive debt from the Seven Years’ War resulted in renewed efforts to consolidate imperial control over North American markets, taxes, and political institutions — actions that were supported by some colonists but resisted by others. In the late 18th century, new experiments with democratic ideas and republican forms of government, as well as other new religious, economic, and cultural ideas, challenged traditional imperial systems across the Atlantic World. The colonists’ belief in the superiority of republican self-government based on the natural rights of the people found its clearest expression in the ideas of the Enlightenment, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and in the Declaration of Independence. The American Revolution occurred because the American colonists, who had long been developing a strong sense of autonomy and self-government, furiously resisted British attempts to impose tighter imperial controls and higher taxes after the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. The sustained conflict over political authority and taxation, enhanced by American agitators and British bungling, gradually moved Americans from asserting rights within the British Empire to openly warring with the mother country. The resulting independence movement was fueled by established colonial elites, as well as by grassroots movements that included newly mobilized laborers, artisans, and women. When hostilities began in 1775, the colonists were still fighting for their rights as British citizens within the empire, but in 1776 they declared their independence, based on a proclamation of universal, self-evident truths. Inspired by revolutionary idealism, they also fought for an end to monarchy and the establishment of a free republic. Despite considerable loyalist opposition, as well as Great Britain’s apparently overwhelming military and financial advantages, the patriot cause succeeded because of the colonists’ greater familiarity with the land, their resilient military and political leadership, their ideological commitment, and their support from European allies. American independence was recognized by the British only after the conflict had broadened to include much of Europe. American diplomats were able to secure generous peace terms because of the international political scene: Britain's recently reorganized government favored peace and France's inability to make good on its promises to Spain.