Mesopotamia Ancient: Mesopotamia

advertisement

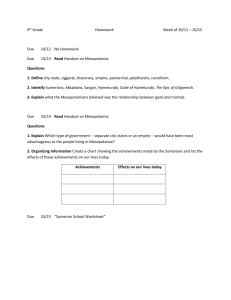

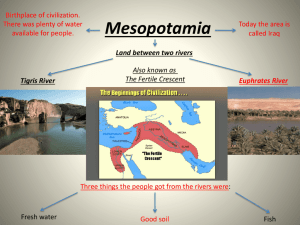

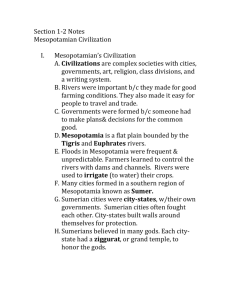

Ancient: Mesopotamia Mesopotamia Some of the world’s earliest civilizations emerged in a region called Mesopotamia, meaning “between the rivers,” in modern day Iraq. By 3500 B.C.E. a number of cities, including Ur and Uruk, emerged sharing a common culture known as Sumerian. These cities, surrounded by protective walls, were more than a mile in diameter and home to more than 30,000 people. Most residents were farmers, living in huts made of sun-baked mud bricks, who tended their crops by day in nearby fields. But other city-dwellers, supported by the farmers' surplus food, specialized in other occupations. Their numbers included artisans, merchants, laborers, priests and priestesses, soldiers, and government officials. Conflict was common among Sumerian cities, many of which were city-states, independent urban political domains that controlled the surrounding countryside. Eager to enhance their power and wealth, larger city-states sometimes sought to swallow up others, provoking periodic wars. Leaders who emerged in combat often became kings and officials. Over time the kings amassed power to command armies, levy tribute and taxes, dispense justice, and organize the building of roads, canals, and dikes. In many places kingship became hereditary, as rulers passed on power to their sons, reflecting the patriarchal structure of Sumerian society and families. Officials helped the kings govern, while priests and priestesses exalted them as descendants of the gods. Royal authority was thus reinforced by religion. The most famous Sumerian ruler was King Gilgamesh, hero of the Epic of Gilgamesh, a magnificent narrative poem from the third millennium B.C.E. In this epic the handsome young king, described as part god and part man. Confronted by gods, Gilgamesh searches for immortality, only to learn that eternal life is beyond his grasp. The epic exhibits fundamental features of Mesopotamian religion. Like many ancient belief systems, it was polytheistic, meaning that people worshiped more than one god. Gods and goddesses personified forces central to agricultural society, such as earth, sun, water, sky, fertility, and storms who were temperamental figures, portrayed in human form and believed to affect every aspect of life. But overall outlook was gloomy: humans had to serve unpredictable and spiteful gods in this life, with little hope for better fate in the next life. Religion nonetheless played a central role in early societies. It supplied an explanation for the forces of nature, and a way for people to try to influence those forces. It provided a focus for festivals, such as new year holidays in spring, celebrating life's natural cycles with rituals, dances, and songs. It exalted rulers as divine agents, enhancing their authority and helping them maintain order. Priests and priestesses, often family members or devoted followers of rulers, heralded the rulers as godlike beings descended from divinities and performed rituals intended to bring divine favor on the realm. To further enhance their status and prestige, rulers built splendid temples to the gods and palaces for themselves. Some Sumerian cities constructed ziggurats, massive brick towers ascending upward in tiers, typically topped by shrines for religious rituals. Dominating urban landscapes, ziggurats also served as symbols of power and as lookout towers for defense. Governance and religion were thus intertwined, each supporting the other. Secured by this support and sustained by surplus food, Sumerians made great strides in other endeavors. They promoted regional commerce, pioneered the use of wheels, fashioned metals into tools and weapons, devised ways to keep track of time, performed architectural and engineering feats, and invented writing. Although Sumer's farms produced abundant wheat and barley, and its sheep supplied ample wool, woods and metals there were scarce. So Sumerians traded with other lands, exchanging their textiles and grains for cedar wood and copper from the eastern Mediterranean, gold from Egypt, and gems from what is now Iran. To carry these goods, Sumerians fashioned wooden boats for rivers, cargo ships for seas, and wheeled carts to be pulled overland by animals. Sumerians also made advances in metalwork. In the fourth millennium B.C.E., metalworkers began to mix molten copper with tin, thereby producing a sturdier metal called bronze, which was used to make swords and shields for soldiers and sometimes knives and axes for farmers. Other innovations, too, are credited to Sumerians. They created a calendar based on cycles of the moon and a double-entry bookkeeping method. They devised a computation system based on segments of 12 and 60, still used now for dividing time into hours, minutes, and seconds. And they developed architectural and engineering skills to build palaces, temples, fortifications, and irrigation systems. Furthermore, as trade and tribute expanded and society grew more complex, Sumerians devised symbols to record financial and administrative transactions. As this system improved, they also used it to record rituals, laws, and legendary exploits of rulers such as Gilgamesh. This momentous invention, which we call writing, facilitated governance, enhanced commercial connections, and vastly aided the preservation and transmission of knowledge. Sumerians wrote by inscribing figures in wet clay, which hardened into tablets, some of which still exist today. They etched symbols from right to left, using wedgelike characters that scholars now call cuneiform. At first these were merely stylized pictures of people, animals, and objects such as carts, houses, baskets, and bowls. Eventually, however, as characters were added to express ideas and sounds, writing became very complex, so schools were set up in palaces and temples to train writing specialists, or scribes. Few Sumerians learned to write, but those who did played a key role in spreading and preserving their culture. So useful, indeed, was their writing system that it was adopted by outside conquerors seeking to unite and rule all Mesopotamia. Conquest was crucial in spreading Sumerian culture. Beginning around 2350 B.C.E., the Sumerian city-states were conquered by Akkadians, temporarily connecting the region under a common government. The Akkadians also established a pattern repeated throughout history: conquerors learned from societies they conquered and helped spread their culture. The Akkadians, for example, adopted the Sumerian calendar, writing system, and computation methods, introducing them to other regions as Akkad's empire expanded. Soon Mesopotamia’s central location led to the Akkadians being overthrown by nomadic invaders. The pattern of conquest and adaptation was repeated as the nomadic invaders briefly united Mesopotamia under the Babylonian Kingdom around 2000 BCE. Babylon's most notable ruler was Hammurabi, who reigned from 1792 to 1750 BCE and issued the famous law code bearing his name. Hammurabi 's code, sought to regulate matters such as trade and contracts, marriage and adultery, debts and estates, and relations among social classes. It assigned penalties based on retribution—the famous principle of "an eye for an eye"—attempting not only to deter crimes but also to limit retaliation by ensuring that punishments did not exceed the damage done. The code provides many insights into Mesopotamian society. It reveals, for example, that society was hierarchical, divided into nobles, commoners, and slaves, with different penalties depending on social status. A noble who knocked out another noble's tooth, for example, would have his own tooth knocked out ("a tooth for a tooth"), but a noble who knocked out a commoner's tooth only had to pay a fine. The code also shows that society was patriarchal, with men having greater rights and status than women. Marriages were contractual, arranged by the parents of the bride and groom. A husband could legally have a mistress, or even a second wife if his first one had no children. But a woman who cheated or ran off on her husband could be 2 cast in the water to drown. Women did have some rights: they could buy and sell goods and own property, which they were allowed to inherit and pass on to descendants. For all his accomplishments, Hammurabi failed to establish an enduring regime. Following his death in 1750 B.C.E., the Babylonian kingdom declined and was eventually overrun by warlike nomads. 3