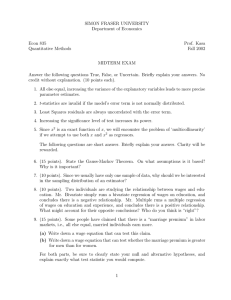

Anup Malani January 20, 2006

advertisement