GAPS IN MODELS/METHODS USED IN THE ASSESSMENT OF

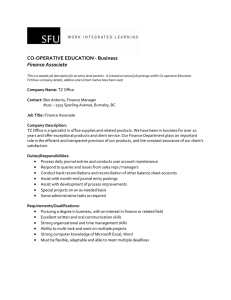

advertisement