Removing Barriers to Higher Education for Undocumented Students By Zenen Jaimes Pérez

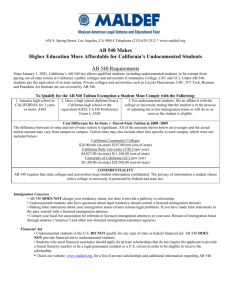

advertisement