The State of Higher Education in California September 2015

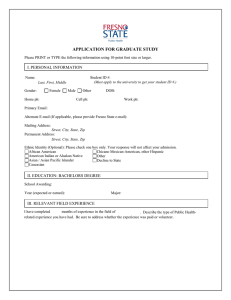

advertisement