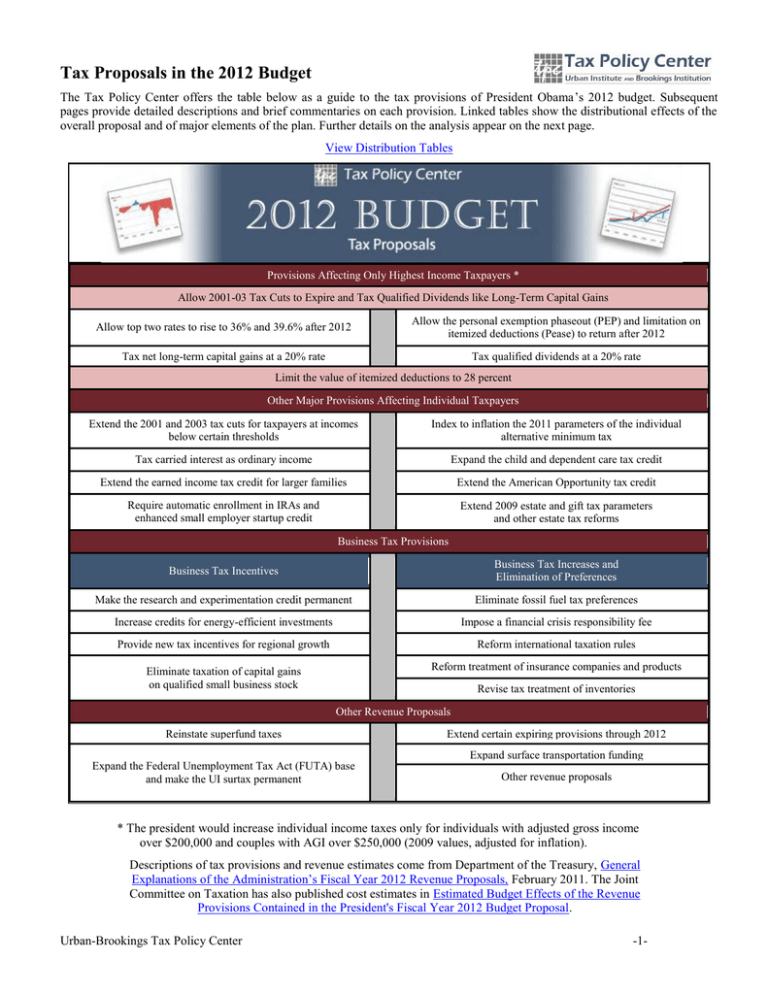

Tax Proposals in the 2012 Budget

advertisement