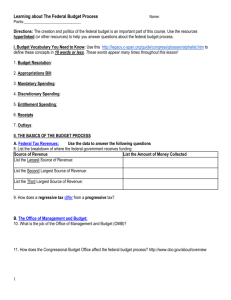

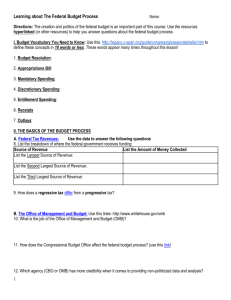

The Hard Road to Fiscal Responsibility 2012 Public Financial Publications, Inc.

advertisement