AN ANALYSIS OF TED CRUZ’S TAX PLAN February 16, 2016

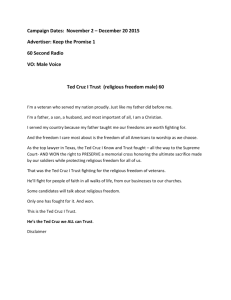

advertisement