Document 14249801

advertisement

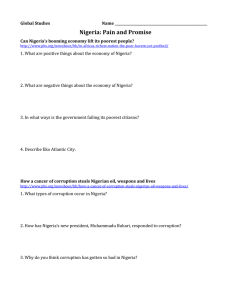

Journal Research in Peace, Gender and Development (JRPGD) Vol. 4(1) pp. 8-14, February, 2014 DOI: http:/dx.doi.org/10.14303/jrpgd.2014.007 Available online http://www.interesjournals.org/ JRPGD Copyright © 2014 International Research Journals Review Citizenship, indigeneship and settlership crisis in Nigeria: understanding the dynamics of Wukari crisis 1 Jaja Nwanegbo, *2Jude Odigbo and 3Ngara Christopher Ochanja 1,*2 Department of Political Science, Federal University, Wukari, Wukari- Nigeria. National Institute for Legislative Studies, National Assembly, Abuja, Nigeria. *Corresponding author email: judeodigbo@gmail.com; +2348037549721 3 ABSTRACT This study examined citizenship, indigeneship and settlership crisis in Nigeria with a view to explaining the violent conflicts of February and May 2013 in Wukari, Taraba State. The paper contended that the several inter-ethnic conflicts between the Junkuns and the Tivs, Kutebs, and the Hausa settlers in the past were significant in shaping the dynamics of the recent Wukari crisis. It adopted focus group discussions, observation technique as well as secondary method of data analysis. With the aid of Marx’s conflict view point, the paper argued that the Wukari crisis was as a result of accumulated grievances, anger and frustration arising from suspicion, mutual distrust and manipulative indigeneship and citizenship status in the struggle for power and scarce communal resources between minority Jukun Muslims and majority Jukun Christians cum Traditionalists. The paper recommended that government at all levels and Wukari community leaders would collaborate and constitute a joint reconciliatory panel to resolve outstanding grievances through dialogue and town hall meetings and ensure that relevant laws are reviewed in the on-going constitutional amendment process to give all Nigerians sense of belonging wherever they reside. It also recommended the establishment of mass media outfit to bridge information gap among the people. Keywords: Indigenship, Settlership, Citizenship, Crisis and Wukari. INTRODUCTION Globally, communal crisis, religious, ethnic, inter and intra-state conflicts appear to have remained the most destabilizing feature of politics in the third world countries especially in Africa. In Nigeria, since the return to civil rule in 1999, domestic instability arising from ethnoreligious, inter and intra communal conflicts of varying degrees and dimensions have been recorded. The implications of these crises to national security, development and democratic survival and consolidation are well captured in the works of Jega, (2002); Osaghae and Suberu, (2005); Nwaomah, (2011); Egwu, (2013); Nwanegbo (2012); Salawu, (2010); Osaghae, (1992); Fawole and Bello, (2011); Imobighe, (2003); and Egwu (2003). The humanitarian tragedies that have accompanied these ethno-religious violence have been prohibitive (Egwu, 2013:26; Nwanegbo 2012:29). Studies over the years have shown that indigene/ settler dichotomy and issues of citizenship that is rooted in the nebulous national constitutional misconstruction and discriminatory tendencies of elitist politics have been the reinforcing factors for ethno-communal violence in Nigeria (see Ojukwu and Onifade, 2010; Aluaigba, 2008). Thus, the political use and misuse of citizenship and indigeneship has promoted dual conceptual explanations and application of the notion of indigeneity. In this regard, a Nigerian citizen may be excluded or denied opportunities in Nigeria owing to his/her parental genealogy. Nigerians, who have their ethnic genealogy elsewhere, even if they were born in a particular state or lived all their lives there, are regarded as “settlers” (Ibrahim, 2006). This discriminatory tendency especially at the local levels has been a major and potential source of conflict. For instance, discrimination on the basis of indigeneship or citizenship is quiet problematic because it is directly tied to individual or group access to societal resources including political opportunities. This has Nwanegbo et al. 9 served to further sharpen the “we” and the “you” divide. It should be noted that ethnic conflicts in 1959, 1980, 1990, 1994, 1991, 1992 and 2001 between the Jukuns and the Tivs, Kutebs and Hausa settlers have had far reaching impact on the Jukuns people (see Mustapha 2002). Today, the popular use of indigene/settler as a means of discriminating against other ethnic groups or separating owners of the land from migrants has become an important factor in the socio-political life of the Jukun society. In fact, for the Christian Jukuns and the traditionalists, the Jukuns/Hausa Muslims are settlers and should be prevented from playing central role in the affairs of the Jukuns and/or partaking in opportunities meant for the Jukuns. Conversely, Jukun Muslims or those with Hausa blood (regarded by the Christian/Traditionalists Jukuns as Hausa people) have equally strong claim to the Jukun society as land of their paternal or maternal ancestry and thus see themselves as equal stakeholders in all Jukun affairs. These discriminatory tendencies over the years have led to the buildup of accumulated grievances and tension among the Jukuns. Thus, the football argument that led to the gruesome murder of a non Muslim youth on the football pitch on the February 23, 2013 and the consequent violence was just a trigger that unbounded long years of mutual anger, frustration, suspicion and mistrust. The crises led to massive human and material destruction. Till date, the number of casualties have not been ascertained especially when evidences on ground surpass the number of people reported to have been killed. The crisis dislocated many families, shut down businesses and property worth millions were destroyed. An even more disturbing fact is that residency in Wukari town is now patterned along religious divide. While the Christian/traditionalists Jukuns occupy the part of the town (regarded as the main Jukun land), the Jukun Muslim/ Hausa settlers occupy the other parts (regarded as the settler’s quarters). Indeed, the above scenario has raised fundamental questions on what constitutes citizenship in Nigeria. What are the implications and dangers associated with the usage and application of indigene-settler issues? Is it to limit individuals or group access to community resources and dispensation of political opportunities? What is responsible for misconception and juxtaposition of citizenship with indigeneship in Nigeria? To what extent has this contradiction sustained perennial conflicts in Wukari? The aim of this study is to examine the historical experiences of Jukuns ethno-religious conflicts with their neighbors with a view to determining how this history has contributed to the recent fratricidal conflicts in Wukari between Christian/Traditionalists Jukun on one side and Jukun Muslims and Hausa settlers on the other. Problematizing Citizenship in Nigeria In most recent years, there has been unimaginable high spate of conflicts in Nigeria and the threat of others (Nwanegbo, 2012:24). It is undisputable fact that millions of Nigerians find themselves living in states, communities or among ethnic groups they have ever known. This situation is not peculiar to a particular zone, region or place. In fact, different ethnic nationalities have conceived and adapted different attitudes to what connotes citizenship in Nigeria, making effort at resolving citizenship problems almost impossible. Thus, constitutional loopholes seem to have exacerbated citizenship crisis in Nigeria. For instances, Section 147 of the 1999 Constitution states that indigene of each state shall be considered in ministerial appointment without explicit definition of the term indigene. The concept of indigeneship in Nigeria has been subject to manipulation. Many interpretations are assigned to it by different groups, ethnic nationalities and persons for the purpose of excluding others and/or gaining economic and political advantage. According to Ibrahim in Yisa (2005:8), the consequences of Section 147 of the 1999 Constitution is that it has created four types of Nigerians: The lucky ones who belong to the indigenous communities of the state of residence; the indigenes of other states who are expected to go back to their own states for any benefits; Nigerians who are unable to prove membership of any indigenous group in any state of the country and women who are married to men in states other than their own, who are neither accepted in their states of origin nor in their husbands (Ibrahim cited in Yisa, 2005:8). Explaining this further, Egwu (2013:27) posits that what obtains in Nigeria is a bifurcated system of citizenship by which a pan-Nigerian notion of citizenship operates at the national level while indigeneity operates at the local level. For him, this ignores the rich history of migration and constant mingling of Nigerian peoples and creates a distinction between “indigenes” and “nonindigenes” or between “natives” and “settlers” (Egwu, 2013: 27). Thus, the controversies and complexities of citizenship in Nigeria could be explained from the outcome of politics that necessitated its usage. In this direction, citizenship is used to gain access to power, employment, claim benefits and sometimes ensures denial to others. The implication is perennial conflict arising from disagreement among individuals, groups and ethnic nationalities. Thus, the spate of recent violent conflicts in Wukari, Taraba State can be mirrored from the perspective of a struggle by the Jukuns with mixed blood to assert or integrate themselves into the mainstream of the Jukun political, administrative and as well as traditional space. This attempt seems to have been resisted by the Christian/Traditional Jukuns owing to suspicion that the Jukun Muslims (also seen now as settlers) have cultivated alliances and close relationship with other ethno-religious groups particularly the Hausa settlers in order to establish socio-economic and political 10 J. Res. Peace Gend. Dev. base. The mutual distrust and suspicion among them is further compounded by information gap resulting in the distortion of information, spread of falsehood and rumors thereby causing a major crack among the Jukun people who were united just a decade ago against their Tiv neighbours in a communal warfare. The vestiges of carnage left on Wukari town almost a decade after the Tiv-Jukun conflicts speak volume of the impact of the recent crisis on the psychic and socioeconomic development of the people and the state at large. The 1994 the Tiv/Jukun conflict in Wukari led to the death of an estimated 5,000 people (Hudgens and Grillo cited in Egwu, 2013:27). Salawu (2010:347) states that the killing of 19 soldiers by the Tiv group in 2002 led to military invasion that cost the lives of more than hundred and sixty (160) people. In the recent Wukari crisis of 2013, the National Emergency Agency (NEMA), put the number of displaced at over 3,000 persons (see Itodo, 2013). Beyond the humanitarian issues generated by the recent crisis, it is noteworthy to assert that Wukari is endowed with arable land and has over the years attracted the Tivs who are mainly farmers and many people from various parts of the country. Most of these people eke their living through farming at subsistent and commercial levels as well as other small scale businesses thereby reducing the pressure on government and the private sector for employment opportunities. The recurring crisis in Wukari has not only dislocated families from their base, but also forced many business concerns to relocate to neighbouring towns. The implication of this exodus is that the enormous natural and human resources in Wukari would remain relatively untapped with severe consequences for socio-economic development. Citizenship, Indigeneship-Settlership Conceptual and Theoretical Discourses. Crisis: Many states in Africa especially in the post-colonial era seem to face the challenges of citizenship. This is mainly because of colonial legacy of “divide and rule” that has created a sense of superiority among aborigines and inferiority among migrants or settler citizens in the same country of nationality. This has produced a situation in which a former president and a former prime minister have been declared not to be citizens of the countries they were president and Prime Minister – Zambia and Cote d’ivoire respectively (Obe, 2004:277). This precarious situation has made Obe (2004) to observe that one must necessarily approach issues of citizenship with a good deal of circumspection. The indigene principle first appeared in the Native Authority Law of 1954, which defined an indigene as “someone whose genealogy can be traced to particular geo-ethnic space within a local council or state in which s/he is resident” (International Crisis Group Africa, 2012:3). In contrast, a non-indigene, settler or stranger is a “native who is not a member of the native community living in the area of its authority” (International Crisis Group 2012). An indigene is one who claims to be the ‘son’ of the soil, a recognized citizen of a given space while a non indigene or settler is a stranger, a migrant who does not have rights of occupancy (Ojukwu and Onifade, 2010:175). In the post colonial Nigerian society, indigene could be seen as one whose lineage is traced to a specific place or community and as well being recognized by others as one of the legitimate owners of the place. In fact, place of birth, conferment or naturalization can only guarantee citizenship of Nigeria but does not actually offer someone the status of an indigene. It is no surprise that in many communities where people have migrated or settled for more than three decades in Nigeria, the people are hitherto addressed as settlers. And they are persistently discriminated from other rights and privileges due to them as a citizen. These practices often nurture lots of grievances among the people especially at the rural areas, semi-urban communities where these crises emanate and have serious negative consequences. On the other hand, citizenship according to Gauba (2003:269) denotes the status of an individual as a full and responsible member of a political community. He further states that citizenship is the product of a community where the right to rule is decided by a prescribed procedure which expresses the will of the general body of its members. While ascertaining their will, nobody is discriminated on grounds of race, religion, gender, place of birth (Gauba, 2003). Thus, citizenship is a relationship between the individual and the state in which both are linked by reciprocal rights and duties (Ifesinachi, 2010:1). For him, citizenship in the modern state seems to proceed from the continuum of individualism and communalism. Liberal citizenship advances the principle of ‘citizenship right’ and places particular stress on private entitlement and the status of the individual as an autonomous actor (Heywood, cited in Ifesinachi, 2010). Marshall in Egwu, (2009: 188) further explains that it is much easier to define citizenship as a status bestowed on those who are full members of a community. For him, all those who possess the status of citizens are equal with respect to the rights and duties with which the status is endowed”. Following from the above, one could decipher major problems associated with citizenship related issues in Nigeria. This is because it appears increasingly difficult to determine who is a full member of a particular environment in Nigeria especially when the major variable in determining such is tied to land ownership in most places thereby reinforcing the indigene/settler crisis. Thus, Nigeria in it’s over half a century independent existence and over a decade of democratic practice is still grappling with plethora of ethno-religious and communal conflicts arising from citizenship, indigene- Nwanegbo et al. 11 settler feud. The constitutional ambiguity and controversy surrounding the definition of citizenship in Nigeria seems to have stalled scholarly efforts at achieving accepted definition of the concept as many are concerned with rights and obligations of a citizen. Indeed, misconception or misuse of citizenship and indigeneship/settlership in Nigeria has provoked numerous violent conflicts across the country (see Egwu, 2013; Ojukwu and Onifade, 2010; Norwegian Refugee Council, 2003; Aluaigba, 2008). Hence, such violence tends to undermine the importance and relevance of citizenship especially within the context of migration, national integration and development. Explaining the major cause of indigene/settler crisis in Nigeria, Aluaigba (2008:12) posited that a more plausible explanation lies in the failure of the Nigerian state to web its numerous ethnic nationalities through the conscious creation of a national structure that will enhance equal rights and justice and access to social welfare for all individuals and groups. For him, these centrifugal identities built around religion, ethnic groupings, ‘indigeneity’, ‘settlership’, ‘nativity’, ‘migrants’, ‘nonindigenes’ ‘southerner’, ‘northerner’ etc have collectively sharpened the dividing line between Nigerians thus making cohesive nationhood a more convoluted task. The 1999 constitution seems to be clouded in providing explicit legal direction for the Nigerian citizenship. For instance, Section 42 of Chapter IV of the Constitution provides for the right to freedom from discriminations. It also states that, a citizen of Nigeria of a particular community, ethnic group, place of origin, sex, religion or political opinion shall not (a) be subjected to disabilities or restriction to which citizen of Nigeria of other communities, ethnic groups, places of origin, sex, religions, political opinions are not made subject or (b) be accorded any privilege or advantage that is not accorded to citizen of Nigeria of other communities, ethnic groups, places of origin, sex, religious or political opinions (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999). However, the federal character principle tends to pose serious threat in determining the functionality of the above provisions. Beyond the issue of fetching mediocre to leadership positions, federal character principle tends to have encouraged denial and discrimination among Nigerians. For instance, the appointment of former finance minister from Lagos was keenly contested by the Lagos state government based on his indigeneity. In his view, Aluba (2009), argued that: the current constitution is duplicitous in dealing with the indigene/ settler questions. It espouses universal criteria for Nigerian citizenship but also recognizes indigenes for purposes of appointment of ministers. In daily existence, residency is discarded in favour of indigene/ settler. Again, where is the national unity, especially that there is no opportunity for settlers to convert to indigenes? The experience underscores the nature of one country where citizens have different structures of opportunities not because of any objective criteria but due to ethnic origins. This situation perhaps explains why previous peaceful coexistence between ethnic and religious groups is now blighted by regular bouts of violence (Alubo, 2009:15). Indeed, the problem of citizenship in Nigeria today largely stems from the discriminations and exclusion meted out to people on the basis of ethnic, regional, religious and gender identities (Adesoji and Alao, 2009). This according to them is because those who see themselves as “natives” or “indigenes” exclude those considered as “strangers” from the enjoyment of certain rights and benefit that they ought to enjoy as Nigerians upon the fulfillment of certain civic duties, such as the payment of tax. The implication is that the political system has continued to witness ethno-religious, communal and political conflicts of immense proportion that posed serious threat to unity, peace and development in Nigeria. The inability of the Nigerian state to evolve a legal framework that would effectively resolve the uncertainty surrounding citizenship could be well explained with Marx’s conflict theory. The mode of production, for Marx determines the super structure and the corresponding social relationships i.e., polity, and religion, law, etc. Similarly, social structure and the forces of production and social relations of distributions constitute the foundation for understanding the nature of human society (Ritzer, 1996). One of Marx main assumption is that the emergence of modern state has reproduced irreconcilable differences among men and made conflict inevitable. This is because the state has created different classes with inherent contradictions which produce class struggle with political derivations (see Akpuru-Aja, 1997; Ritzer, 1996). Thus, the citizenship, indigene/settler crisis in Nigeria and particularly in Wukari cannot be divorced from colonial policy of divide and rule consolidated by post colonial elite drive to exploiting ethno-religious gap for political reasons and to sustain class competition among the various ethnic elite groups. The struggle by the different ethnic nationalities in Nigeria over scares national resources has necessitated the manipulation of indigeneship/citizenship issues by individuals, groups to gain political and economic advantage and to exclude others. The attempt by those excluded to assert or integrate themselves into the mainstream of social, economic and political life of their community against the resistance of those at the mainstream has been the major factor in explaining most of the ethno-religious and communal violence in Nigeria. A Brief Historical Perspective of the Jukuns Wukari is a town in Taraba State-one of the States in North-East Nigeria. Apart from being the traditional and cultural headquarter of the Jukuns and many minority tribes and ethnic group like the Alago, Agatu, Awe, Etilo, etc in some of the present north-central states who 12 J. Res. Peace Gend. Dev. Jukun rulers of Wukari, with title "Aku Uka" Between 1833 till Date Ruler Zikenyu Tsokwa Tasefu Agbumanu I Agbu Ashumanu II Jibo Kindonya Awudumanu I Abite Agbumanu II Agbunshu Ashumanu III Ali Agbumanu III Amadu Ashumanu IV Angyu Masa Ibi Agbumanu IV Atoshi Ashumanu V Adi Byewi Awudumanu II Abe Ali Agbumanu V Adda Ali Shekarau Angyu Masa Ibi Kuvyon II Commencement Year 1833 1845 1860 1871 1903 1915 1927 1940 1945 1960 1970 1974 1976 End of the Reign 1845 1860 1871 1903 1915 1927 1940 1945 1960 1970 1974 1976 Till date Adapted from Wikipedia retrieved 6/6/2013 migrated alongside the Jukuns from the ancient Kwararafa Kingdom in Sudan, it is the administrative headquarter of Wukari Local Government Area. The town which was established earlier before colonialism is renowned for its historical significance as the modern headquarters of the Kwararafa Kingdom. The Jukun were established in Wukari from Sudan as early as the 17th century. The paramount leader is known or rather addressed as the Aku Uka of Wukari which is symbolic as it represents the centre of the Jukun people. The Jukuns were predominantly traditionalists prior to the advent of Christianity and Islam. Their adherence to rituals and traditional beliefs of complex character appear to have played a significant part in the retention of their cultural and societal values and beliefs till date. The pre-colonial Jukun society is classified into the Jukun Wanu and Jukun Wapa with the Wanus’ mainly fishermen. Thus, the belligerent character of the primitive Jukun society that is rooted in territorial expansionist tendencies and the drive to acquire more subjects led to power tussle and confrontations that disintegrated kwararafa Kingdom and the consequent migration of most of other tribes such as; Alago, Agatu, Rendere, Gumai in Shendam, and others who left Kwararafa (see Wikipedia). With the Fulani conquests at the beginning of the 19th century, the Jukun-speaking peoples became politically divided into various regional factions (Wikipedia retrieved 13/7/2013). By 1920s, according to Meek (1931:8) the Jukuns lived in scattered groups around the Benue basin, in an area that roughly corresponded to the extent of the kingdom of Kwararafa as it existed in the 18th century. He further explained that: by the 1920s, the main body of the Jukun population, known as the Wapâ, resided in and around Wukari, where they were governed by the local king and his administration. Other Jukun-speaking peoples living in the Benue basin, such as those of Abinsi, Awei District, Donga and Takum, remained politically separate from the Wukari government, whilst the Jukun-speakers living in Adamawa Province recognised the governorship of the Fulani Emir of Muri (Meek, 1931). In spite of this early divided loyalty, the Jukun throne in Wukari has remained firm and resolute in administering and providing traditional leadership since the 18th century. Indeed, till date, thirteen (13) Jukuns have ascended the throne of Aku Uka showing in the Table above. However, it is important to note that cross-border migratory influences, religious and cultural contacts with other cleavages have nurtured some conflicts between the Jukuns and most of its neighbours. The pre-colonial era was characterized by wars and conflicts because of the expansionist tendencies of the Jukuns to extend the territorial space of the kwararafa kingdom and to acquire more subjects. The colonial era was also marred with the British divide and rule polices. With this policy most of the Jukuns remained politically divided resulting in the conscious or unconscious transfer of political allegiance and loyalty by some Jukuns to other politically organized thrones. The socio-economic and political expediency of the present day Nigeria has not helped matters. More often than not, the socio-political context have aided the process of further division along socio-cultural, religious, economic and political lines thus resulting in flashpoints of violence and confrontations especially since the return to democratic rule in 1999. Wukari Crisis: The Building Blocks. The Jukuns have experienced long years of violent conflicts with their neighbours especially in the post colonial Nigerian state. Apart from intermittent crisis arising from expansionist tendencies of the Kwararafa Kingdom, the pre-colonial Jukun society appeared relatively peaceful and friendly. Anifowose (2003:49) explained that peaceful co-existence between the Tivs and the Jukuns predates colonialism. Indeed, the present unrest and animosity are by-products of previous colonial and immediate post-colonial inter-communal and religious experience. This historical antecedence to a greater extent is fundamental in shaping the perceptions, Nwanegbo et al. 13 attitudes and behaviours of the Jukun people in contemporary Nigerian society. The genesis of the conflicts between the Jukuns and their neighbours and more specifically the Tiv has been traced to the colonial period. Avav and Myegba explained that the British created a wedge between the Tivs and Jukuns in the well known colonial policy of “divide and rule” thus, engendering unhealthy rivalry between them (cited in Jibo, 2001:2). In the view of Jibo (2001), violent hostilities was dated back immediately before and after 1956 federal elections in which the Tivs who were predominantly members of the United Middle Belt congress (UMBC) fielded a candidate, Charles Tangur Gadza, who defeated a Jukun opponent Sangari Usman of the Northern People’s Congress (NPC). For him, majority of Jukuns felt that since the Tivs with their population advantage had secured seven federal seats, it would be logical to cede Wukari Federal seat to a Jukun. This embarrassment, which the Jukun suffered, amidst the newly discovered political prowess of the Tiv in Wukari, in part, contributed to the outbreak of the Tiv riot of 1959-60, and again in 1964 (Best and Idyorough 2003:177). For them, the existing hostilities and division between the Tiv and Jukun at this time simply abetted the conflict which was marked by larger scale killings and destruction of property, and population displacement. This scenario appeared to have added more ill-feelings on the existing acrimonious “colonial divide and rule” policy. Thus, in 1991/92, the Tivs and Jukuns engaged in a serious conflict (Norwegian Refugee Council 2003:19). The youths were heavily involved in the crisis, blocking major roads, erecting illegal checkpoints along the roads and killing each other and destroying property worth millions Naira (Nigerian currency). Constant reprisal attacks by both sides resulted in the deaths of many. Between October 2001 and January 2002, land dispute between the Tivs and Jukuns culminated in a total breakdown of law and order. The Jukuns declared their Tiv neighbours settlers, hence they are not entitled to any land in Jukun communities. Other conflicts that have impacted negatively on the socio-economic development of Wukari and indeed the lives of the Jukuns are the Jukun-Chamba/Kuteb conflicts which has been going on for years, although there has been no large scale fighting since 1999. The killing of a paramount chief in Kuteb and the boundary disputes arising from some communities from Takum refusal to join Ussa local government area were remote and immediate causes of the Jukun-Chamba/Kuteb violence. The February and May 2013 Episodes The year 2013 and precisely February 13 and May 4 would go down the memory lane for the Jukuns as one of the most turbulent years in which they killed each other, monumentally inflicted injuries among themselves and destroyed property worth millions of Naira. As we noted earlier, the remote cause of the fratricidal conflict can be attributed to an accumulated grievances among the Jukuns arising from several years of ill-feelings, frustration and grudge due to discrimination on the basis of indigene/settler dichotomy. Thus, what triggered the recent violence was a mere argument between two football enthusiasts which snowballed into a bloody battle with deep religious sentiment (see Mkom, 2013; Itodo, 2013; Ayodele, 2013). In the heat of the altercation, one person used pistol and killed his opponent which immediately attracted mob action. The angry mob lynched the accused and the act aggravated the crisis to what could best be described as bloodbath. Hundreds of private residential houses, business shops were burnt and many people perished. The violence and carnage was brought under control following the deployment of troops and the imposition of a twenty four (24) hours curfew which lasted for over a month. Similarly, in May, 2013 while the soldiers were still on ground, the Jukuns engaged in yet another major violent confrontation against themselves after widespread rumors of reprisal attacks were ignored by government officials and security operative. The violence was sparked by an attempt by some groups (alleged to be Hausas) in the Karofi area of the town to prevent some traditionalists from carrying out burial rites procession for a deceased traditional Chief, Abe Ashumate, the Abon Ziken of the town. The incident developed into a full blown confrontation and within hours of the conflict, hundreds of people were brutally murdered. Though, there were conflicting reports on the number of people killed, the available reports put death toll at hundred (100) (see Ayodele, 2013), while about 300 houses were burnt (Mkom, 2013). The violence crumbled socio-economic activities for weeks; families were forced to migrate to neighbouring villages and towns, the educational system was badly affected as schools were shutdown including the two universities (Federal University Wukari and Kwararafa Univiersity-private) located in Wukari main town. Other dominant tribes particularly the Igbos who survived the crisis relocated with their businesses to “safe-haven” with heavy negative implications for socioeconomic development of Wukari and by extension the Taraba State at large. The reoccurring violence in Wukari has thrown up several fundamental issues for intellectual analysis which relate to indigene/settler contestation. The impacts of these crises on socio-economic political relations have been fundamental. It has led to the erection of new residency and settlement pattern along ethnic and religious divide with the Jukun Christian/Traditionalists occupying one part of the town and the Hausa/Jukun Muslims occupying the other. The psychological impact on both the adult and younger generation of those who witnessed and experienced these conflicts has left a lot of 14 J. Res. Peace Gend. Dev. unresolved queries that would require long years of concerted effort at peace and confidence building to heal the emotional wounds that have been inflicted as a result of the violence. CONCLUSION From our analysis, it has been established that citizenship, indigene/settler dichotomy is germane in understanding the remote causes of grievances that are responsible for the recent fratricidal crisis in Wukari. While we are not oblivious of the relative peace in place, it is our position that the peace is unsustainable if concerted effort is not made towards resolving fundamental issues that have propelled these conflicts in the first instance. In this regard, we recommend that there is an urgent need for the review of the extant laws bearing on indigeneship and citizenship in the on-going process of the review of the 1999 constitution. Accordingly, indigeneship should be replaced with residency for a few stipulated years. Massive public awareness campaign and enlightenment programme on the need for peaceful co-existence is recommended. Also, town hall meetings on issues of common interests are encouraged. To bridge communication gap among the people, government should set up radio and television stations to meet the information needs of the people and to dislodge the present trend of reliance on rumors. Finally, there is need for federal, state and local governments in collaboration with the Wukari community leaders to constitute joint reconciliation panel that would ensure amicable resolution of grievances, misunderstanding and fears harbored by the people over the years in order to guarantee long lasting peaceful coexistence among the Jukuns. REFERENCES Adesoji A, Alao A (2009). Indigeneship and Citizenship in Nigeria: Myth and Reality. The J. Pan Afr. Studies. 2(9): 151-165. Akpuru-Aja A (1997). Theory and Practice of Marxism in a World in Transition. Abakaliki: Willrose Publ. Pp. 52. Aluaigba MT (2008). The Tiv-Jukun Ethnic Conflict and the Citizenship Question in Nigeria. Aminu kano Center for Democratic Res. and Training Kano: Bayero University. Pp. 12. Anifowose R (2003). “The Changing Nature of Ethnic Conflicts: Reflections on the Tiv- Jukun Situation”. In Tunde Babawale (Ed.), Urban Violence, Ethnic Militias and the Challenge of Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria. Lagos: Malthouse Press Limited. Ayodele W(2013). “Wukari Boils Again” Thisday May 4, 2013. Pp. 2. Best S, Idyorough A(2003). Population Displacement in the Tiv-Jukun Communal Conflict. In O. Nnoli (Ed.), Communal Conflict and Population Displacement in Nigeria. Enugu: Pan African Centre for Res. on Peace and Confl. Resol. Pp. 182. Egwu S (2003). “Ethnicity and Citizenship rights in the Nigerian Federal State”. In A. Gana and S. Egwu (Eds.), Federalism in Africa Trenton: Africa World Press. Egwu S (2009). “The Jos Crisis and the National Question” Sunday Guardian January 25, 2009. Pp. 12. Egwu S (2013). Ethno-Religious Conflicts and National Security. The Dawn. 5(2): 26- 38. Fawole OA, Bello ML (2011). The Impact of Ethno-Religious Conflicts on Nigerian Federalism. Int. NGO J. 6(10): 211-218. Federal Republic of Nigeria (1999). The 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Lagos: Federal Government Press. Gauba OP(2003). An Introduction to Political Theory. Delhi: Macmillan India Ltd. Ibrahim J (2006). ‘Expanding the Human Rights Regime in Africa: Citizens, Indigenes and Exclusion in Nigeria’, In L. Wohlgemath and E. Sall (Eds.), Human Rights, Regionalism and the Dilemmas of Democracy in Africa, Dakar: CODESRIA. Ifesinachi K (2010). The Rentier State, Global Liberalism and Citizenship in Nigeria. University of Nigeria J. Pol. Econs.. 4(2): 114. Imobighe TA (2003). Ethnicity and Ethnic Conflicts in Nigeria: An Overview. In T.A. Imobighe (Ed.), Civil Society and Ethnic Conflicts Manage. in Nigeria. Ibadan: Spectrum. International Crisis Group (2012). Curbing Violence in Nigeria: The Jos Crisis. Africa Report No. 196. Itodo DS (2013). “Wukari Crisis: One Violence Too Many” Weekly Trust, May 11, 2013. Pp. 8. Jega AM (2002). Tackling Ethno-Religious Conflicts in Nigeria. The Nigeria Social Sci. 5(2): 35-39. Jibo M (2001). The 2001 Tiv Massacre: Accountability and Impunity in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic. University of Jos J. Pol. Sci. 2(3): 1-13. Meek CK (1931). A Sudanese Kingdom: An Ethnographic Study of the Jukun-speaking Peoples of Nigeria. London: Kegan Paul, Trubner & Co. Mkom J (2013). “5 Killed, 300 Hundred Houses Burnt in Taraba Crisis” The Sun, February 24, 2013. Pp. 1 and 6. Mustapha R (2002). ‘Transformation of Minority Identities in Post Colonial Nigeria’. In A. Jega, (Ed.), Identity Transformation and Identity Politics under Structural Adjustment in Nigeria, Kano, Centre for Res. and Documentation. Norwegian Refugee Council (2003). Profile of Internal Displacement: Nigeria. Global IDP. Nwanegbo J (2012). Internal Conflicts and African Development: The Nigerian Experience. J. Humanities and Social Sci. 5(4): 22-33. Nwaomah SM(2011). Religious Crisis in Nigeria: Manifestation, Effects and the Way Forward. J. Sociol. Psychol. Anthropol. in Practice. 3(2): 94-104. Obe A (2004). Citizenship, individual rights and the Nigerian constitution. In A. B Agbaje, L. Diamond and E. Onwudiwe (Eds), Nigeria’s Struggle for Democracy and Good Governance. A Festschrift for Oyeleye Oyediran: Ibadan University Press. Ojukwu CC, Onifade CA(2010). Social Capital, Indigeneity and Identity Politics: The Jos Crisis in Perspective. African J. Pol. Sci. Int. Relations. 4(5): 173-180. Osaghae EE (1992). “Ethinicity and Democracy” In A. Fasoro (Ed.), Understanding Democr. Ibadan: Book Craft Limited. Osaghae EE, Suberu RT (2005). A History of Identity, Violence and Stability in Nigeria. Centre for Res. on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity: Oxford University. Ritzer G(1996). Sociological Theory 4th ed. New York: The McGraw-Hill Co. Inc. Salawu B (2010). Ethno-Religious Conflicts in Nigeria: Causal Analysis and Proposals for New Management Strategies. European J. Social Sci. 13(3): 345-359. Wikipedia (2013). History of Wukari retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wukari_Federation. Wikipedia (2013). The Jukuns of Nigeria retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jukun_people_%28West_Africa%29. Yisa S(2005). Settler vs Indigene Issues in the Context of Peace Education for Meeting the Challenges of Nigerian Nationhood. A Paper Present at the National Conference on Peace Edu. and the th Challenges of Nigerian Nationhood: Minna. June 26 . How to cite this article: Nwanegbo J, Odigbo J and Ochanja NC (2014). Citizenship, indigeneship and settlership crisis in Nigeria: understanding the dynamics of Wukari crisis. J. Res. Peace Gend. Dev. 4(1):8-14