Mission Integration With Pope Francis and Catholicism Today

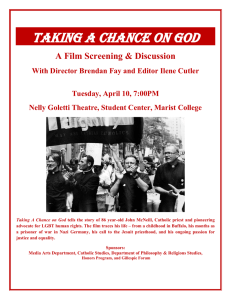

advertisement