H A R T N E L L ... Board of Trustees – Study Session

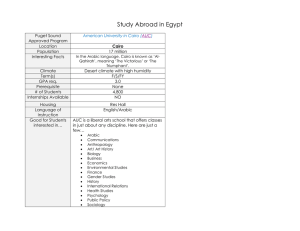

advertisement