Domestic Partner Benefi ts at the University of Houston

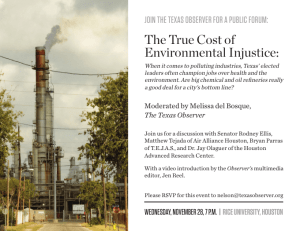

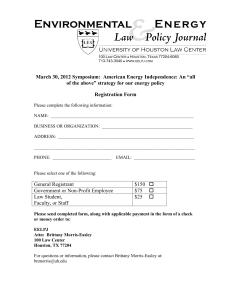

advertisement