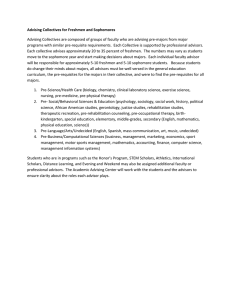

U n i v e r s i t y ...

advertisement