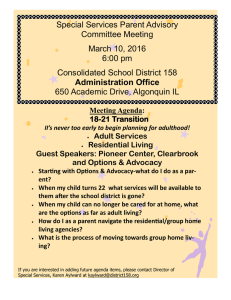

America’s Housing Policy— the Missing Piece Residential

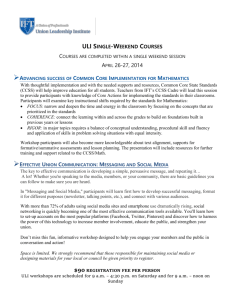

advertisement