Decipherment with a Million Random Restarts

advertisement

Decipherment with a Million Random Restarts

Taylor Berg-Kirkpatrick

Dan Klein

Computer Science Division

University of California, Berkeley

{tberg,klein}@cs.berkeley.edu

Abstract

This paper investigates the utility and effect of

running numerous random restarts when using EM to attack decipherment problems. We

find that simple decipherment models are able

to crack homophonic substitution ciphers with

high accuracy if a large number of random

restarts are used but almost completely fail

with only a few random restarts. For particularly difficult homophonic ciphers, we find

that big gains in accuracy are to be had by running upwards of 100K random restarts, which

we accomplish efficiently using a GPU-based

parallel implementation. We run a series of

experiments using millions of random restarts

in order to investigate other empirical properties of decipherment problems, including the

famously uncracked Zodiac 340.

in accuracy even as we scale the number of random restarts up into the hundred thousands. In both

cases the difference between few and many random

restarts is the difference between almost complete

failure and successful decipherment.

We also find that millions of random restarts can

be helpful for performing exploratory analysis. We

look at some empirical properties of decipherment

problems, visualizing the distribution of local optima encountered by EM both in a successful decipherment of a homophonic cipher and in an unsuccessful attempt to decipher Zodiac 340. Finally, we

attack a series of ciphers generated to match properties of Zodiac 340 and use the results to argue that

Zodiac 340 is likely not a homophonic cipher under

the commonly assumed linearization order.

2

1

Introduction

What can a million restarts do for decipherment?

EM frequently gets stuck in local optima, so running

between ten and a hundred random restarts is common practice (Knight et al., 2006; Ravi and Knight,

2011; Berg-Kirkpatrick and Klein, 2011). But, how

important are random restarts and how many random

restarts does it take to saturate gains in accuracy?

We find that the answer depends on the cipher. We

look at both Zodiac 408, a famous homophonic substitution cipher, and a more difficult homophonic cipher constructed to match properties of the famously

unsolved Zodiac 340. Gains in accuracy saturate after only a hundred random restarts for Zodiac 408,

but for the constructed cipher we see large gains

Decipherment Model

Various types of ciphers have been tackled by the

NLP community with great success (Knight et al.,

2006; Snyder et al., 2010; Ravi and Knight, 2011).

Many of these approaches learn an encryption key

by maximizing the score of the decrypted message

under a language model. We focus on homophonic

substitution ciphers, where the encryption key is a

1-to-many mapping from a plaintext alphabet to a

cipher alphabet. We use a simple method introduced

by Knight et al. (2006): the EM algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977) is used to learn the emission parameters of an HMM that has a character trigram

language model as a backbone and the ciphertext

as the observed sequence of emissions. This means

that we learn a multinomial over cipher symbols for

each plaintext character, but do not learn transition

parameters, which are fixed by the language model.

We predict the deciphered text using posterior decoding in the learned HMM.

3

Experiments

We ran experiments on several homophonic substitution ciphers: some produced by the infamous

Zodiac killer and others that were automatically

generated to be similar to the Zodiac ciphers. In

each of these experiments, we ran numerous random

restarts; and in all cases we chose the random restart

that attained the highest model score in order to produce the final decode.

3.1

Experimental Setup

The specifics of how random restarts are produced

is usually considered a detail; however, in this work

it is important to describe the process precisely. In

order to generate random restarts, we sampled emission parameters by drawing uniformly at random

from the interval [0, 1] and then normalizing. The

corresponding distribution on the multinomial emission parameters is mildly concentrated at the center

of the simplex.2

For each random restart, we ran EM for 200 itera1

0.9

We used a single workstation with three NVIDIA GTX 580

GPUs. These are consumer graphics cards introduced in 2011.

2

We also ran experiments where emission parameters were

drawn from Dirichlet distributions with various concentration

parameter settings. We noticed little effect so long as the distribution did not favor the corners of the simplex. If the distribution did favor the corners of the simplex, decipherment results

deteriorated sharply.

-1470

0.8

-1480

Implementation

0.7

Accuracy

Running multiple random restarts means running

EM to convergence multiple times, which can be

computationally intensive; luckily, restarts can be

run in parallel. This kind of parallelism is a good

fit for the Same Instruction Multiple Thread (SIMT)

hardware paradigm implemented by modern GPUs.

We implemented EM with parallel random restarts

using the CUDA API (Nickolls et al., 2008). With a

GPU workstation,1 we can complete a million random restarts roughly a thousand times more quickly

than we can complete the same computation with a

serial implementation on a CPU.

-1460

Log likelihood

Accuracy

0.6

0.5

-1490

-1500

0.4

Log likelihood

2.1

1

-1510

0.3

-1520

0.2

0.1

-1530

1

10

100 1000 10000 100000 1e+06

Number of random restarts

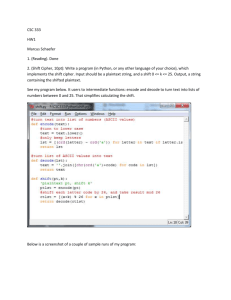

Figure 1: Zodiac 408 cipher. Accuracy by best model score and

best model score vs. number of random restarts. Bootstrapped

from 1M random restarts.

tions.3 We found that smoothing EM was important

for good performance. We added a smoothing constant of 0.1 to the expected emission counts before

each M-step. We tuned this value on a small held

out set of automatically generated ciphers.

In all experiments we used a trigram character

language model that was linearly interpolated from

character unigram, bigram, and trigram counts extracted from both the Google N-gram dataset (Brants

and Franz, 2006) and a small corpus (about 2K

words) of plaintext messages authored by the Zodiac

killer.4

3.2

An Easy Cipher: Zodiac 408

Zodiac 408 is a homophonic cipher that is 408 characters long and contains 54 different cipher symbols. Produced by the Zodiac killer, this cipher was

solved, manually, by two amateur code-breakers a

week after its release to the public in 1969. Ravi and

Knight (2011) were the first to crack Zodiac 408 using completely automatic methods.

In our first experiment, we compare a decode of

Zodiac 408 using one random restart to a decode using 100 random restarts. Random restarts have high

3

While this does not guarantee convergence, in practice 200

iterations seems to be sufficient for the problems we looked at.

4

The interpolation between n-gram orders is uniform, and

the interpolation between corpora favors the Zodiac corpus with

weight 0.9.

Also in Figure 1, we plot a related graph, this time

showing the effect that random restarts have on the

achieved model score. By construction, the (maximum) model score must increase as we increase the

number of random restarts. We see that it quickly

saturates in the same way that accuracy did.

This raises the question: have we actually

achieved the globally optimal model score or have

we only saturated the usefulness of random restarts?

We can’t prove that we have achieved the global optimum,5 but we can at least check that we have surpassed the model score achieved by EM when it is

initialized with the gold encryption key. On Zodiac

408, if we initialize with the gold key, EM finds

a local optimum with a model score of −1467.4.

The best model score over 1M random restarts is

−1466.5, which means we have surpassed the gold

initialization.

The accuracy after gold initialization was 92%,

while the accuracy of the best local optimum was

only 89%. This suggests that the global optimum

may not be worth finding if we haven’t already

found it. From Figure 1, it appears that large increases in likelihood are correlated with increases

in accuracy, but small improvements to high likelihoods (e.g. the best local optimum versus the gold

initialization) may not to be.

5

ILP solvers can be used to globally optimize objectives

corresponding to short 1-to-1 substitution ciphers (Ravi and

Knight, 2008) (though these objectives are slightly different

from the likelihood objectives faced by EM), but we find that

ILP encodings for even the shortest homophonic ciphers cannot

be optimized in any reasonable amount of time.

0.8

-1280

0.75

-1285

0.7

Accuracy

0.65

-1290

0.6

Log likelihood

Accuracy

0.55

-1295

0.5

-1300

0.45

0.4

Log likelihood

variance, so when we present the accuracy corresponding to a given number of restarts we present an

average over many bootstrap samples, drawn from

a set of one million random restarts. If we attack

Zodiac 408 with a single random restart, on average we achieve an accuracy of 18%. If we instead

use 100 random restarts we achieve a much better

average accuracy of 90%. The accuracies for various numbers of random restarts are plotted in Figure 1. Based on these results, we expect accuracy

to increase by about 72% when using 100 random

restarts instead of a single random restart; however,

using more than 100 random restarts for this particular cipher does not appear to be useful.

-1305

0.35

0.3

-1310

1

10

100 1000 10000 100000 1e+06

Number of random restarts

Figure 2: Synth 340 cipher. Accuracy by best model score and

best model score vs. number of random restarts. Bootstrapped

from 1M random restarts.

3.3

A Hard Cipher: Synth 340

What do these graphs look like for a harder cipher?

Zodiac 340 is the second cipher released by the Zodiac killer, and it remains unsolved to this day. However, it is unknown whether Zodiac 340 is actually a

homophonic cipher. If it were a homophonic cipher

we would certainly expect it to be harder than Zodiac 408 because Zodiac 340 is shorter (only 340

characters long) and at the same time has more cipher symbols: 63. For our next experiment we generate a cipher, which we call Synth 340, to match

properties of Zodiac 340; later we will generate multiple such ciphers.

We sample a random consecutive sequence of 340

characters from our small Zodiac corpus and use

this as our message (and, of course, remove this sequence from our language model training data). We

then generate an encryption key by assigning each

of 63 cipher symbols to a single plain text character so that the number of cipher symbols mapped to

each plaintext character is proportional to the frequency of that character in the message (this balancing makes the cipher more difficult). Finally, we

generate the actual ciphertext by randomly sampling

a cipher token for each plain text token uniformly at

random from the cipher symbols allowed for that token under our generated key.

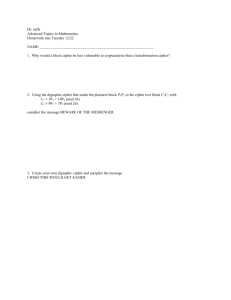

In Figure 2, we display the same type of plot, this

time for Synth 340. For this cipher, there is an abso-

60000

50000

14000

42%

ntyouldli

12000

59%

veautital

10000

Frequency

Frequency

40000

30000

8000

6000

20000

4000

10000

2000

74%

veautiful

0

0

-1340 -1330 -1320 -1310 -1300 -1290 -1280 -1270

Log likelihood

Figure 3: Synth 340 cipher. Histogram of the likelihoods of the

local optima encountered by EM across 1M random restarts.

Several peaks are labeled with their average accuracy and a

snippet of a decode. The gold snippet is “beautiful.”

lute gain in accuracy of about 9% between 100 random restarts and 100K random restarts. A similarly

large gain is seen for model score as we scale up the

number of restarts. This means that, even after tens

of thousands of random restarts, EM is still finding

new local optima with better likelihoods. It also appears that, even for a short cipher like Synth 340,

likelihood and accuracy are reasonably coupled.

We can visualize the distribution of local optima

encountered by EM across 1M random restarts by

plotting a histogram. Figure 3 shows, for each range

of likelihood, the number of random restarts that

led to a local optimum with a model score in that

range. It is quickly visible that a few model scores

are substantially more likely than all the rest. This

kind of sparsity might be expected if there were

a small number of local optima that EM was extremely likely to find. We can check whether the

peaks of this histogram each correspond to a single

local optimum or whether each is composed of multiple local optima that happen to have the same likelihood. For the histogram bucket corresponding to a

particular peak, we compute the average relative difference between each multinomial parameter and its

mean. The average relative difference for the highest

peak in Figure 3 is 0.8%, and for the second highest

peak is 0.3%. These values are much smaller than

-1330

-1320

-1310 -1300

Log likelihood

-1290

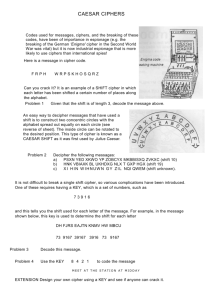

-1280

Figure 4: Zodiac 340 cipher. Histogram of the likelihoods of the

local optima encountered by EM across 1M random restarts.

the average relative difference between the means of

these two peaks, 40%, indicating that the peaks do

correspond to single local optima or collections of

extremely similar local optima.

There are several very small peaks that have the

highest model scores (the peak with the highest

model score has a frequency of 90 which is too

small to be visible in Figure 3). The fact that these

model scores are both high and rare is the reason we

continue to see improvements to both accuracy and

model score as we run numerous random restarts.

The two tallest peaks and the peak with highest

model score are labeled with their average accuracy

and a small snippet of a decode in Figure 3. The

gold snippet is the word “beautiful.”

3.4

An Unsolved Cipher: Zodiac 340

In a final experiment, we look at the Zodiac 340

cipher. As mentioned, this cipher has never been

cracked and may not be a homphonic cipher or even

a valid cipher of any kind. The reading order of

the cipher, which consists of a grid of symbols, is

unknown. We make two arguments supporting the

claim that Zodiac 340 is not a homophonic cipher

with row-major reading order: the first is statistical,

based on the success rate of attempts to crack similar

synthetic ciphers; the second is qualitative, comparing distributions of local optimum likelihoods.

If Zodiac 340 is a homophonic cipher should we

expect to crack it? In order to answer this question

we generate 100 more ciphers in the same way we

generated Synth 340. We use 10K random restarts to

attack each cipher, and compute accuracies by best

model score. The average accuracy across these 100

ciphers was 75% and the minimum accuracy was

36%. All but two of the ciphers were deciphered

with more than 51% accuracy, which is usually sufficient for a human to identify a decode as partially

correct.

We attempted to crack Zodiac 340 using a rowmajor reading order and 1M random restarts, but the

decode with best model score was nonsensical. This

outcome would be unlikely if Zodiac 340 were like

our synthetic ciphers, so Zodiac 340 is probably not

a homophonic cipher with a row-major order. Of

course, it could be a homophonic cipher with a different reading order. It could also be the case that

a large number of salt tokens were inserted, or that

some other assumption is incorrect.

In Figure 4, we show the histogram of model

scores for the attempt to crack Zodiac 340. We note

that this histogram is strikingly different from the

histogram for Synth 340. Zodiac 340’s histogram is

not as sparse, and the range of model scores is much

smaller. The sparsity of Synth 340’s histogram (but

not Zodiac 340’s histogram) is typical of histograms

corresponding to our set of 100 generated ciphers.

4

Conclusion

Random restarts, often considered a footnote of experimental design, can indeed be useful on scales

beyond that generally used in past work. In particular, we found that the initializations that lead to the

local optima with highest likelihoods are sometimes

very rare, but finding them can be worthwhile; for

the problems we looked at, local optima with high

likelihoods also achieved high accuracies. While the

present experiments are on a very specific unsupervised learning problem, it is certainly reasonable to

think that large-scale random restarts have potential

more broadly.

In addition to improving search, large-scale

restarts can also provide a novel perspective when

performing exploratory analysis, here letting us argue in support for the hypothesis that Zodiac 340 is

not a row-major homophonic cipher.

References

Taylor Berg-Kirkpatrick and Dan Klein. 2011. Simple effective decipherment via combinatorial optimization. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

Thorsten Brants and Alex Franz. 2006. Web 1t 5-gram

version 1. Linguistic Data Consortium, Catalog Number LDC2009T25.

Arthur Dempster, Nan Laird, and Donald Rubin. 1977.

Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM

algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society.

Kevin Knight, Anish Nair, Nishit Rathod, and Kenji Yamada. 2006. Unsupervised analysis for decipherment

problems. In Proceedings of the 2006 Annual Meeting

of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

John Nickolls, Ian Buck, Michael Garland, and Kevin

Skadron. 2008. Scalable parallel programming with

CUDA. Queue.

Sujith Ravi and Kevin Knight. 2008. Attacking decipherment problems optimally with low-order n-gram

models. In Proceedings of the 2008 Conference on

Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

Sujith Ravi and Kevin Knight. 2011. Bayesian inference

for Zodiac and other homophonic ciphers. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Association for

Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies.

Benjamin Snyder, Regina Barzilay, and Kevin Knight.

2010. A statistical model for lost language decipherment. In Proceedings of the 2010 Annual Meeting of

the Association for Computational Linguistics.