Document 14234003

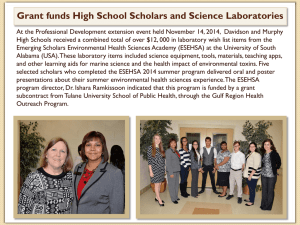

advertisement