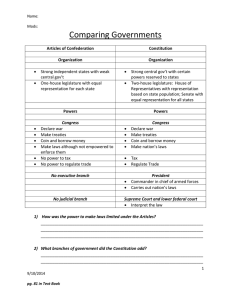

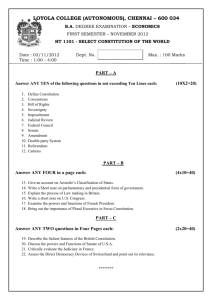

UNIT II CONSTITUTIONAL UNDERPINNINGS AND THE BRANCHES OF GOVERNMENT

advertisement