Using Systems Thinking to Facilitate Organizational Change

advertisement

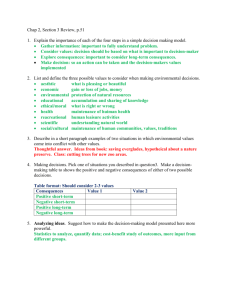

Using Systems Thinking to Facilitate Organizational Change David Peter Stroh © 2004, www.bridgwaypartners.com There is an old adage in change management: “People don’t resist change; they resist being changed.” Leaders want people to embrace change as a natural process, rather than not resist it. What do we know about what motivates people to embrace change? What are the implications of this knowledge for successful change leaders? What actions do they take that cultivate people’s intrinsic desire to change, and what qualities do they embody to be effective with minimum effort? Through my own extensive experiences over thirty years in developing myself, furthering individuals’ growth, and advising leaders of organizational change, I have come to recognize several key principles that support natural change and growth: Both discomfort and safety are required The truth will set you free Commitment follows clarity Make a few key changes Engage others in the process, not just the product Bring in the reinforcements Container Building: Establishing the Foundation for Change The purpose of container building is to develop readiness for change. Senior OD consultant Ed Schein notes that the primary challenge in initiating change is creating sufficient discomfort that people feel the need to change, and sufficient safety that they are willing to take the necessary risks involved in learning something new. The metaphor of container building describes the process of constructing a vessel that is strong enough to safely hold the uncertainty and difficulty that most change entails. Imagine a cooking pot: the sides of the container hold the heat that is required to transform the individual ingredients into a nourishing dish. In order to create discomfort and safety in a system, leaders first cultivate these qualities in themselves. They have sufficient passion to achieve a better future, and the requisite self-confidence to take risks. In addition, they develop a supportive coalition or core group that agrees with what they want to accomplish, but also represents different views about how to best achieve the results. Change leaders create discomfort in a system by articulating the discrepancy between the current and desired states. For example, early in his tenure at General Electric, Jack Welch noted that GE would be first or second in every one of its markets, and clarified the current performance of each business with respect to this standard. He complemented the challenge he set forth with mechanisms intended to help people feel capable of making such a change: personal attention; training, coaching and consulting resources; the “workout” methodology designed to help managers increase the productivity of their businesses; and an emphasis on adherence to new values as the basis for initial performance evaluations. People in a strong container move through five stages as they change: Clarity Compassion Commitment Choice Courage These 5 C’s provide a useful mnemonic. More importantly, they inform change leaders about qualities they need to embody and steps they need to take to help people and organizations grow. While the following qualities are presented here as linear steps, successful change leaders often weave them together in practice. Clarity and Compassion: The Truth Will Set You Free Change leaders create a shared picture of current reality to motivate change, foster collaboration, and identify where to focus limited resources to make significant and lasting change. They develop a shared picture of not only what is happening, but also why it is happening. Leaders also help people understand how they frequently contribute to the very problems they are trying to solve. Moreover, leaders couple confronting people with their responsibility for current reality with compassion for the fact that most people are unaware of their responsibility. Telling the truth about reality begins with testing the assumption that we already know the way things are. People often deny existing problems or ignore a problem that is likely to get worse if not addressed now. Alternatively, they know that a problem exists or might unfold, but deny that they have any role in addressing it. They are certain about who is to blame for the problem, and even assume what others should be doing to solve it. Finally, people might be reluctant or unable to deal with conflicting views regarding what is wrong, why the problem exists, who is responsible, and what should be done to solve it. Overcoming Resistance to Seeing Reality Clearly Change leaders address the obstacles of denial, certainty, and conflict to help people develop a more accurate assessment of reality. One natural antidote to denial is curiosity – a desire to understand the sources of our frustration and the world around us. Leaders stimulate curiosity in the course of softening denial, reducing certainty, and making conflict safe. They also ensure that the organization affirms its strengths and what is important to not only retain but build on. 1) Softening Denial Three ways to reduce denial are: Call attention to the gap between people’s good intentions and negative experiences Introduce feedback from a wide range of sources Ask questions that uncover not only what is happening but also why it is happening Most people have good intentions and are genuinely surprised and frustrated when their hard effort doesn’t produce corresponding results. Hence, one powerful question to ask is, “Why are we having such difficulty in achieving our goals despite our best efforts?” This question communicates support by acknowledging positive intentions and simultaneously questions if success must come at such a high cost. Requiring managers to get feedback from a wide range of sources - for example, both satisfied and dissatisfied customers, employees on the front lines, high potential leaders, and colleagues - often confronts them with the reality that performance is lower or less sustainable than they imagined. For example, managers who become anonymous customers of their own organization often discover how their real customers are treated. Large group interventions that bring together multiple stakeholders can offer more diverse views of a whole system, and 360-degree feedback provides an individual with a broader perspective. Video feedback also helps people observe their own behavior without being able to easily discount the source of information. It is also useful to ask a series of questions that get below the surface of what is happening to uncover the root causes of specific events. The “Iceberg” is a tool that helps people identify what has been happening over time; what might happen in the future if they do not change the course of events; and what are the underlying policies, processes, procedures, and perceptions that influence and shape current events and trends.1 2) Reducing Certainty Digital Equipment Corporation founder Ken Olsen used to say that nothing concerned him more than success. He pointed out that success leads to complacency and complacency causes people to miss cues that signal a change in the competitive landscape. The attribution is ironic in light of Digital’s failure to anticipate the rise of personal computers, and significant in that even the most successful strategies decay over time and require fresh thinking. Here are some ways to reduce the certainty that what works today will also work tomorrow: 1 Peter Senge, et al, The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook, pgs. 97-103 provides an example; Doubleday, 1994 Consider the limits to growth of your current strategy, for example, constraints in your own resources or the markets you serve, and actions that your “nightmare” competitor could take to undermine your competitive advantage. Develop alternative scenarios of the future and plan what you must do to be successful in the face of uncertain and diverse possibilities. Look for indicators that things are changing. For example, examine what’s different or unusual in other industries or disciplines, track changes in the rates of your own performance growth, and gauge leading indicators such as process effectiveness or morale that could signal changes in results over time if not addressed now. Another form of certainty that hurts an organization is the belief that a problem exists and that others are to blame and must be the ones to change. One way to reduce this certainty is to gather all the key stakeholders in one place and ask them to develop a systems map that describes the full complexity of the problem: the many factors, what these factors impact, and what drives these factors. The complexity of the resulting map usually leads people to realize that their simple hypotheses about what’s wrong, who’s to blame, and what should be done are inaccurate or at least incomplete. It increases their willingness to look more deeply for root causes and effective solutions. 3) Making Conflict Safe One of the greatest barriers to clarifying current reality is the concern that people will see reality differently and not know how to resolve their different views. This is one of the reasons for building a strong container in the first place. Establishing ground rules and providing tools for holding productive conversations around difficult issues is one early step that change leaders can take to help people address conflict. The metaphor of the blind men and the elephant, where several blind men touch different parts of an elephant and swear that it is something else, also frees people up to recognize the inherent limitations in any individual’s or group’s point of view. The aforementioned systems map can help everyone draw the whole elephant, acknowledge both the validity and limits of their own perspective, and create a richer picture of reality that incorporates multiple views. 4) The Power of Appreciative Inquiry Underlying the need to address obstacles of denial, certainty, and conflict is the assumption that people will naturally resist self-criticism. Hence, a very different approach to cultivating curiosity is to ask them to identify what is already working in their organization and how they can build on it. This approach, known as appreciative inquiry, can produce dramatic improvements in effectiveness without raising defensiveness.2 See for example, David Cooperrider, “Positive Image, Positive Action: The Affirmative Basis of Organizing”, in S. Srivasta & D.L. Cooperrider (Eds.), Appreciative Management and Leadership: The Power of Positive Thought and Action in Organizations, Jossey-Bass, 1990 2 I believe that appreciative inquiry works best when it draws people’s attention to core values that the organization wants to cultivate independent of particular circumstances. At the same time, the primary limit to appreciative inquiry is what Gary Hamel calls the “inevitability of strategy decay.”3 As noted, strategies and behaviors that work today might not work in the future. Therefore, in order for people to realize their aspirations, people need to continuously distinguish what they care about from how they need to operate. 5) Removing Barriers to Clarity: An Example The Chairman of a retail conglomerate was concerned about the strategic viability of one of his companies. While the company performed adequately, changes in the competitive landscape indicated that it might not survive without significantly overhauling its strategy. However, the company was very operationally focused and had failed in all previous attempts to initiate strategic company-wide changes. He took several steps to challenge the management team: He replaced the retiring Managing Director, who had been very operational, with a more strategically oriented MD. He hired both a strategy consulting firm and an expert in the company’s market niche to analyze and report on key challenges and opportunities for the company. He also hired an organizational consultant to “breathe life into the strategy.” He was concerned that the management team would not be able to either agree on the strategists’ recommendations or implement them without additional help. These steps had the dual effect of affirming the company’s value and questioning its potential effectiveness. The Chairman’s actions signaled that the company warranted investment, in no small part because of its traditional and extensive presence in communities throughout the company’s home market. The new MD was also younger, favored teamwork over one-on-one management, and brought new enthusiasm to the job. At the same time, the MD’s strategic focus and the use of outside strategy and change consultants paved the way for the management team and the rest of the organization to rethink not only what it needed to focus on, but also how people would have to work differently to survive, if not thrive, in the future. Seeing Reality Clearly Achieving clarity means: Discerning what to build on – and what to let go of – in moving forward Identifying the root causes of problems before trying to solve them Gary Hamel and Liisa Valikangas, “The Quest for Resilience”, Harvard Business Review, September 2003 3 Determining how people are partially responsible for the very problems they are trying to solve Recognizing the payoffs of the way things are Knowing “when to hold them and when to fold them” can be as difficult in management as it is at the card table. Many studies point out that holding to a strong and positive set of values is key to an organization’s long-term success.4 However, values that produce success under one set of conditions can destroy it under different circumstances.5 Moreover, if we hold too tightly to a specific growth strategy, we might discover that competitors attracted to the market by our success force us to change the rules of the game and devise a new strategy to stay ahead. At the same time, learning from one’s own success is essential because it raises pride, builds morale, and verifies homegrown solutions that competitors often find difficult to copy. Leaders cultivate and maintain strengths that are sustainable given likely changes in the environment. Correcting maladjustments to the world around us is a necessary complement to reinforcing what works. Yet people have a tendency to solve problems they don’t fully understand. As a result organizations often implement solutions that either make no difference in the long run or actually make matters worse. The resulting frustration, burnout, and ineffectiveness are ultimately detrimental to both individuals and entire organizations. Therefore, another goal of a change leader is to slow down the rush to solutions by demanding a deeper inquiry into the root causes of complex, chronic problems. For example, the retailer’s incoming Managing Director commissioned an in-depth diagnosis of his organization before deciding on a new strategy for the company. He knew that the company had a very poor track record of implementing organization-wide strategic initiatives and wanted to clarify the root causes of this problem before launching into a new direction. Systems thinking is a very powerful way of uncovering root causes because it illuminates the non-obvious interdependencies among complex organizational (and external) factors.6 In the example, the Managing Director and his team learned that the team’s tendency to rely heavily on a few key leaders and the organization’s strength in fighting fires would undermine any attempts to define and implement new strategies based on a set of clear guiding principles and cross-functional teamwork. We say that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. One reason for this is that complex systems tend to seduce people into taking actions that achieve short-term benefit but often make matters worse in the long run. The retail organization depended on a few 4 See, for example, Arie DeGeus, The Living Company, Longview Publishing, 1997, and James Collins and Jerry Porras, Built to Last, HarperCollins, 1994 5 Edgar Schein, DEC Is Dead, Long Live DEC: The Lasting Legacy of Digital Equipment Corporation, Berret_Koehler, 2003 6 David Stroh, “Leveraging Change: The Power of Systems Thinking in Action”, Reflections, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2000 key leaders and firefighting because these strategies had an immediate positive impact on the company’s survival. At the same time they undermined the company’s ability to utilize more of its resources and build momentum in a new direction – to actually thrive instead of only survive. Thinking systemically helps people recognize how they are in part responsible for the problems they are trying to solve. They can learn how their well-intentioned actions often produce unintended consequences that actually reduce their effectiveness in the long run. Effective leaders know that the goal of taking responsibility is not to allocate blame, but to take back the power that organizations surrender when they inaccurately assume that problems are caused by forces beyond their control. For example, all members of the retail management team, including the “go-to” leaders, saw that their efforts to keep the company afloat prevented them from making the essential strategic adjustments that could enable the company to succeed in the future. Organizations must recognize that there are payoffs as well as costs to maintaining the status quo. The costs to the retail company were obvious: it fought hard every year to barely keep even with its competition, undermined the morale of employees who fought one fire after another, and was losing several of its high potential leaders. Less obvious was the satisfaction that the “go-to” leaders received from being so important, and the adrenalin rush and immediate satisfaction that all of the management team accrued from being in charge of frequent firefighting brigades. Acknowledging the value people get from a seemingly dysfunctional situation is essential to making the hard tradeoffs that are often required to create lasting change. We’ll discuss this more in the upcoming section concerning Commitment. Cultivating Compassion to Support Clarity Confronting people with the truth of what is and their unwitting complicity in creating it works most effectively when it is supported by compassion. We understand the importance of combining these two factors when we talk about practicing tough love or ruthless compassion. For most people, “We know not what we do.” It is easier for us to let go of ineffective patterns of thought and behavior when we contrast the unproductive consequences of these patterns with the good intentions that usually underlie them.7 The classic systems story is one of people whose good intentions lead them to take actions that are effective in the short run, but who fail to realize that these same actions hurt them over time. Change leaders who surface this story with compassion discover its power to stimulate natural change. People can no longer convince ourselves that what they are doing works or will turn out better if they do more of it harder and longer. They can forgive themselves for not seeing the full truth of their situation, and move on to reassess their intentions and strategies in light of new insights. This same management team made significant progress when it realized that the company was stumbling not just in spite of their best efforts, but because of them. 7 See, for example, Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen, Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most, Viking Penguin, 1999 Cultivating compassion is supported by an emphasis on learning. Change leaders communicate, “We did the best we could with what we knew at the time. However, times have changed, and we didn’t anticipate that the things we did that worked in the short-run would have such negative long-run consequences.” Learning how our earlier views were incomplete or inaccurate, how times have changed, or how our short-term successes contributed to our current problems provides an opening to think more comprehensively and productively. We can also anticipate more accurately the consequences of any new solutions we might consider. Commitment: Conducting a Full Comparison of Benefits and Costs It might seem strange to talk about commitment so far along in a change process. However, the power of shared aspiration is not sufficient to motivate change. People are equally if not more committed to their reality, no matter how painful it might appear to be. There is a saying in systems theory that systems are exquisitely designed to achieve what they are achieving right now, however dysfunctional those results might appear.8 For example, the retail management team enjoyed the stimulation and importance of fighting fires even if it was not being as effective as it could be. Other companies get the benefits of reducing short-term costs even though their approaches undermine long-term profitability. Key staff functions get satisfaction from knowing that they are working as hard as they can to be as helpful as they can, even though they are not necessarily getting the results they want. Therefore, it is not sufficient to identify the benefits of changing and the costs of not changing in order for change to occur. People must also become aware of the benefits of not changing and the costs of changing if they are to make an informed decision about what to do (see Figure One: Weighing Costs and Benefits below). Realizing a vision, achieving a mission and goals, and being true to one’s values are all benefits of changing. Poor results, frustration, and burnout are clear costs of not changing. Less obvious are the benefits of not changing and the costs of change. We like being important, being stimulated, being helpful, being right when others are to blame, cutting short-term costs or increasing short-term revenues. We believe they are not only justified but will also ultimately produce the long-term satisfaction we seek. Moreover, we shy away from the risks and uncertainty associated with change. How can we trust that letting go of some of our current payoffs will yield what we say we really want? 8 Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey refer to this phenomenon as competing commitments in their book, How the Way We Talk Can Change the Way We Work, Jossey-Bass, 2000. Figure One: Weighing Costs and Benefits In order for change to naturally occur, people must weigh the value of what they say they want and the costs of not changing against the benefits of not changing and the costs of changing. 1) Benefits of changing Better long-term performance Meet deeper human needs 4) Costs of changing Give up stimulation, selfimportance, etc. of working hard Risk short-term results for longterm effectiveness 3) Benefits of not changing People feel they are working as hard as they can to be successful Others can be blamed for shortfalls 2) Costs of not changing Extraordinary effort yields at best ordinary result Increasing financial pressure, frustration, and burnout We might say that change (C) occurs when C=1 x 2 > 3 x 4 in the diagram above.9 Enabling people to truly commit to what they say they want entails clarifying all four quadrants and honestly assessing if change is worthwhile. For example, the in-group within the retail management team needed to give up their special powers, and the group as a whole needed to give up the stimulation associated with firefighting if they were to create a more coherent and sustainable company. They were able to make the shift because they could see that the costs in terms of uncompetitive performance, stress, burnout, and turnover would only get worse if they continued their current behavior. In addition, they developed a new and more meaningful mission for their work – being at the heart of the communities where their stores were located – that both satisfied their deeper needs for making a positive difference and led them to new ways of improving operational performance. As they experimented with new ways of working, they were also able to see that the costs of changing were lower than they thought: managers from the in-group became more powerful as members of a powerful team in an increasingly competitive company, and real movement on strategic initiatives began to reduce the need for firefighting as a way to survive. Choice and Courage: Two Qualities for Bridging the Gap A gap is created when people simultaneously own what is and commit to what they really want. Bridging the gap then involves making choices about how to best focus limited resources and exhibiting the courage required to stay the course of implementation. 9 This equation was inspired by one developed by David Gleicher, C=ABD>X, where C=change, A=level of dissatisfaction with the status quo, B=clear desired state, C=practical first steps toward the desired state, and X=cost of change. Making Choices Despite statements to the contrary, many leaders and organizations find it difficult to focus their limited resources on a few key priorities. The reasons include: 1. Leaders and their subordinates often assume that more effort will yield greater results. By contrast, they do not consider that fewer initiatives carefully chosen and sustained or sequenced over time are likely to produce even higher impact; these are the leverage points that propel complex systems change. 2. Leverage points are often non-obvious, or they are apparent but unpopular because they require people to accept short-run costs for long-run benefits. 3. Doing a lot is experienced as rewarding, exciting, and significant in and of itself. 4. Saying that some things are more important than others risks excluding certain people. 5. Short-term progress leads managers to incorrectly conclude that they can move onto other things, when in fact problems usually return without continued reinforcement of the solutions that they are implementing. 6. Leaders often underestimate the time it takes to implement change and introduce additional initiatives to push the troops when their original assumptions are proven wrong. 7. New urgent needs tend to crowd out longer term important ones. 8. It is always easier to start something than to finish it, and people are more often rewarded for their initiative than their follow-through. It always makes sense to build on successes and strengths as long as they are sustainable. Using the principle of leverage, successful leaders then discern the few changes that are likely to make the greatest difference. One way that they determine such changes is to identify logical connections between the various possible priorities that are being proposed and the many change initiatives that are already underway.10 For example, the retail company had a proud tradition and committed employees that it wanted to retain. Therefore, it engaged all of its 30,000 employees in revisiting the company’s mission over a six-month period. The management team also determined that how it worked was a critical success factor in making the changes it wanted to make. Cross-functional collaboration over time on a few company-wide strategic initiatives was essential to overcome the firefighting efforts overseen by a few key managers that had kept the company afloat until then. When additional priorities still tended to emerge during the coming year, management recognized that it also had to change its reward structure to support completion of current critical projects over initiation of new ones. Exhibiting Courage While courage is described here as a necessary quality for sustaining implementation, it is also clearly an important attribute in earlier stages of the change process. Beginning with 10 For a more thorough approach to identifying leverage points, see, for example, Daniel Kim and Colleen Lannon, Applying Systems Archetypes, Pegasus Communications, 1997 container building, change leaders take a stand that the status quo is no longer acceptable. They then challenge unquestioned assumptions about what is happening and why, and they surface individual as well as organizational responsibility for current circumstances. They also question the benefits of a seemingly dysfunctional system and support people to take the risk that they will lose those benefits in exchange for a more desirable but uncertain future. When it comes to implementation, change leaders have the courage to stay the course on a program that might produce short-term pain for long-term gain. They recognize that expediency and immediate gratification must sometimes be sacrificed for real effectiveness. At the same time, they ensure sufficient short-term results in a new direction to build momentum. As new successes occur, they resist the temptation to declare victory and move on prematurely. They also continuously learn from experiments without judging their efficacy too hastily. In addition, leaders have the patience and fortitude to engage those not initially involved in the change process, and are willing to address their concerns and resistance as well. In essence, change is implemented in waves, and they realize that new people must retrace the learning path of their predecessors. One excellent checklist for staying the course of implementation and creating a new organizational reality is described in the book Intentional Revolutions.11 The authors identify seven levers that produce significant changes in thinking and behavior when applied in concert: Persuasive communication: making the case for change Participation: involving those affected in the change process Expectancy: resetting expectations and mental models about what brings success Role modeling: walking your talk as a leader Structural rearrangement: redesigning systems and processes Extrinsic rewards: reinforcing new values with positive rewards Coercion: forcing out the people who do not support the change Coercion, used sparingly and early on in a change process, can sometimes be the most difficult lever to pull. Jack Welsh relates that people only got the message that he was serious about cultural as well as performance change at GE when he fired several managers who made their numbers but refused to accept the new values he wanted people to adopt. Co-opting or marginalizing resistant stakeholders are related options that change leaders must be willing to employ when necessary.12 For the retail management team, a critical moment of truth came when the company began experiencing shortfalls in its operating performance halfway through the year. Instead of fully retreating on the five strategic initiatives they were leading, the team 11 Edwin Nevis, Joan Lancourt, Helen Vassallo, Intentional Revolutions, Jossey-Bass, 1996 See, for example, W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, “Tipping Point Leadership”, Harvard Business Review, April 2003 12 pulled back only slightly and insisted that employees remain engaged in this work while addressing the immediate performance shortfall. Thanks to their persistence, the company not only achieved its best operating year ever, but also made progress on all five strategic programs. Summary and Conclusions Although we are accustomed to thinking of change as something that has to be forced on people, effective change leaders make change more natural and acceptable. They begin by building a strong container to hold the inevitable tensions and fears that change produces. They cultivate curiosity about why the organization is struggling despite its best efforts, and produce greater clarity about root causes and responsibility for current performance. They communicate compassion for people’s inability to see the consequences of their actions, and revitalize commitment to a direction based on a richer appreciation of the benefits and costs involved. They make strong choices based on a deep understanding of current reality and of the long- as well as short-term consequences of their decisions. They draw on their own innate courage and passion for change while utilizing change levers that send clear signals about what is desirable and required. The 5 C’s articulate both a roadmap for guiding effective change and a set of qualities that leaders can cultivate in themselves as well as their organizations to navigate the terrain.