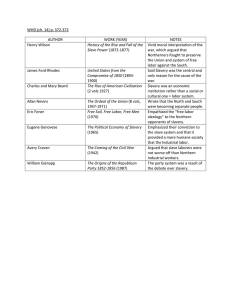

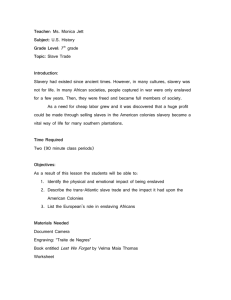

New York and Slavery: Complicity and Resistance Curriculum Guide

advertisement