Perspectives on Social Work

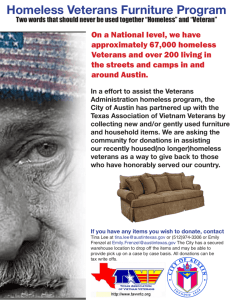

advertisement