Strategies for Bulky Waste Collection in the City of Milwaukee

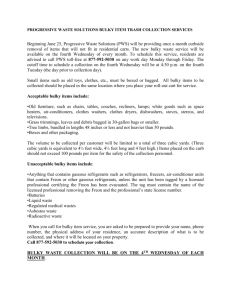

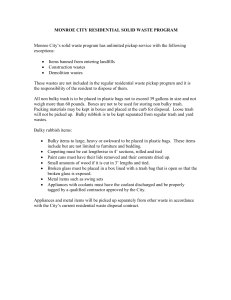

advertisement