Nation-Building in Afghanistan: A Role for NGOs

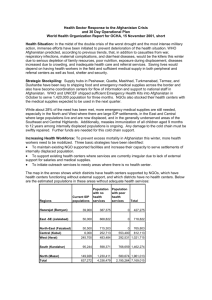

advertisement