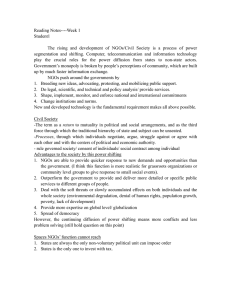

Evaluating NGO Service Delivery in South Asia: Lessons for Afghanistan

advertisement