Economic Development as a Tool to Reduce Secessionism in Jammu

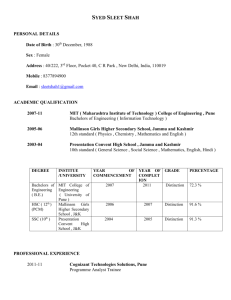

advertisement