Barriers to Building Financial Security for Survivors of Domestic Violence

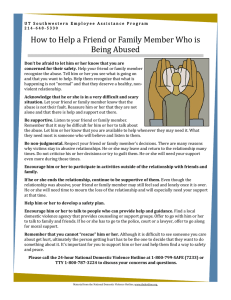

advertisement