An Assessment of Environmental Effects of the 2005 Mexican Automotive Decree

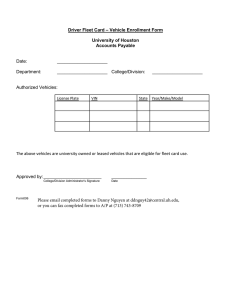

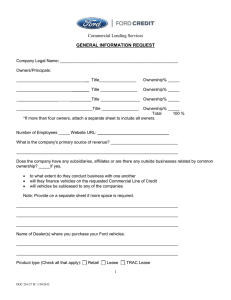

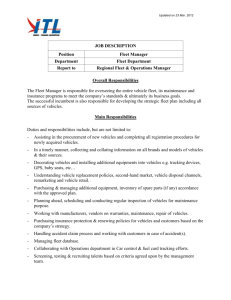

advertisement