An Analysis of Food Safety in Wisconsin

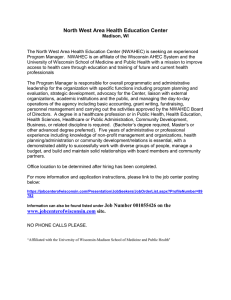

advertisement