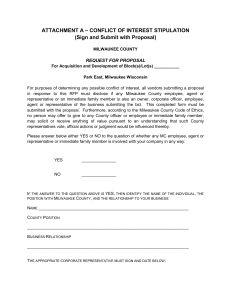

M –L F P

advertisement